‘There is no such thing as ‘free money’, and that has been the case for students since September 1, 2015. Prior to that date, if students graduated within ten years of starting, the entire basic grant (basisbeurs)– approximately 3,000 euros a year – would become a gift, but the loans system has put a stop to this. You have to pay back every last cent the government gives you. And sooner or later, that will include interest.

The interest rate that students pay on their loans is a reflection of the interest the Dutch government pays for any average four-year loan in the capital market. So can the Netherlands borrow money for free? Yes. And better yet: for every thousand euros the country borrows, they receive an extra five euros a year. That is because the interest rate is currently negative, at -0.5 per cent.

Interest

To put it simply, interest is what a loan costs. That price is calculated on the basis of supply and demand in the capital market which, in Europe, is regulated by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Countries can also borrow money in the capital market. This loans process does not differ all that much from how it would work among friends. You would rather loan money to that friend with a good job than the friend who is always broke.

This so-called credit rating is reflected in the interest rate a country has to pay for a loan. The Netherlands, for instance, can borrow at a lower rate than Greece.

Advantageous

There are two reasons for this. First of all, the interest rate in the capital market is already pretty low due to the European Central Bank’s policy. Moreover, the Netherlands have a high credit rating, which means the country can borrow at an advantageous rate. That means students can, too.

But will students be given extra money for their student loans? That is what the CDA wanted to know last October in the Lower House. The answer? Well, no, says spokesperson for the ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) Job Slok. ‘We will not be doing that, because it would cost the country too much money.’

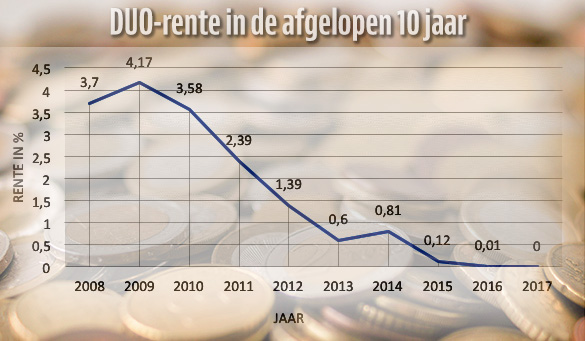

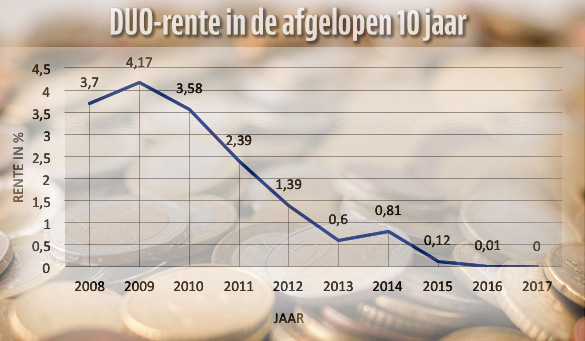

It seemed too good to be true, anyway. But more will be happening starting 1 January, 2017. The interest benchmark – the way the interest is calculated – will also change. Student loan interest will then be linked to the interest for a five-year government loan. And a longer loan automatically means a higher interest rate.

Below zero

The interest differential between a four-year and a five-year government loan is currently a little more than 0.1 percentage points (-0.5 versus -0.388, respectively). This was not always the case: in 2013, for example, the differential was twice as high. As long as the interest rate remains below zero, this does not matter to students.

But the interest rate will eventually be above zero again, and then borrowing money will cost money once more. A few tenths of a percentage point may not seem like much, but if you have to pay off the average student debt of 23,000 euros over 35 years, that quickly adds up to an extra 1,000 to 2,000 euros in interest.

Paying more

The result? Due to the new interest benchmark, students will be paying more for their loans. However, the loans system does allow them to take longer to pay back this loan.

‘Basically, this legislative proposal increases the interest subsidy for students’, says ministry spokesperson Slok. ‘You see, the period the interest is based on has not increased as sharply as the maximum payment term: one year as opposed to twenty years. The country now has to pre-finance this money for much longer and improve in the capital market, a risk that could results in a higher interest rate.’

Pay it back

This may all seem very far away for someone who has just started studying. But sooner or later you will have to face the music and pay back your loans. So how does that work?

Regardless of whether you started before or after 1 September, 2015, you can borrow money for seven years. The interest will start accruing with the first monthly payment. The following year, you will have to pay interest on the interest that has been added to your debt. That is called compound interest.

On 1 January of the year after you graduate (or after you borrowed money for seven years), the interest is fixed for five years. Then there is another two-year reprieve, but after that, you have to start paying back your loan.

In the loans system, the repayment period has been changed from 15 to 35 years, and some other conditions have been changed as well. So your monthly repayment costs will always be lower than in the basic grant system, but the ultimate amount of interest paid will be higher.