Guinea pigs #4Synchronising brains during poker

‘I’m thrilled my bluffs don’t get called’

I don’t think of myself as a skilled bluffer: whenever I play poker, I anticipate losing right away, or I get too tense to really enjoy the game. Yet today, I’ll be playing poker for science.

I’m participating in a study on alexithymia, which Katharina Görlich, assistant professor of cognitive neuroscience – the principal researcher on this study, together with professor André Aleman – explains is a personality trait characterised by ‘being blind to one’s own feelings’.

Today’s experiment aims to find out whether difficulty in understanding emotions affects the ability to bluff. More specifically: people’s brains normally synchronise while bluffing, and this study investigates whether that synchronisation is disrupted between individuals with alexithymia and those without.

Ultimately, by better characterising this condition – which is linked to disorders such as depression and anxiety – they want to help enhance treatment options for those affected.

High score

I don’t think I have alexithymia. As part of this study, I filled out an online questionnaire with twenty statements about feelings. For example: ‘It’s difficult for me to find the right words for my feelings.’ But I’m quite aware of my feelings; I’d say I’m good at expressing them.

That probably means I scored low on the questionnaire – a high score indicates alexithymia. Generally, around 10 percent of people show symptoms of alexithymia. Yet the researchers note that almost a quarter of respondents scored high. That’s striking, since they are mainly psychology students – first-years get credits for participating in these studies.

I meet Malina Misol, a master student at the Free University of Berlin who’s in Groningen for a year to conduct research. Together with Giulia Quagliozzi, a third-year psychology student, and Giacomo Costa, master student of behavioural and cognitive neurosciences, she is preparing the upcoming experiment.

As it involves both bluffing and challenging the bluff, each participant is paired with another. In total, there are 120 participants, forming sixty pairs through various combinations. I’ll be playing with ‘Lea’, a first-year psychology student.

Brain activity

First, the researchers sit me in front of a computer, where I fill out another questionnaire. It takes about ten minutes. Some questions puzzle me, such as ‘I like to get revenge on others’ or ‘Payback needs to be quick and nasty’.

I learn later on that these questions are part of self-report scales designed to assess information about depression, anxiety, and the dark triad (psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism). The questionnaire was included to identify any factors that could affect the study’s results.

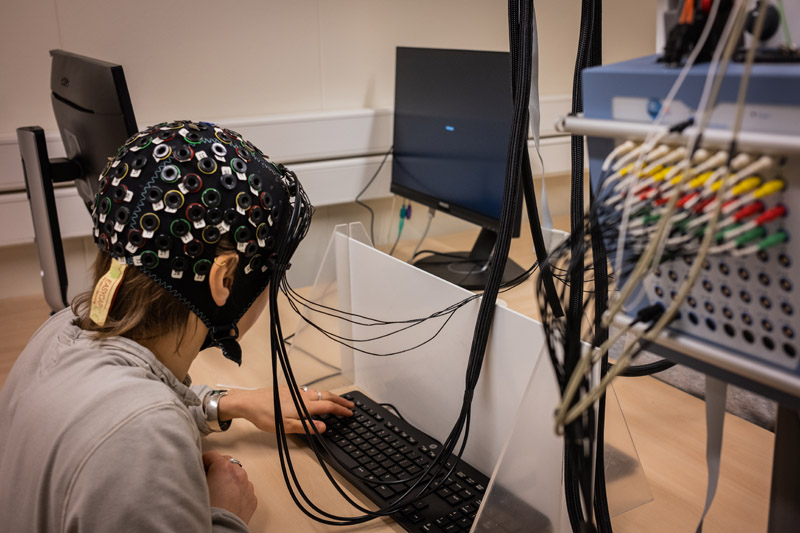

Next, Malina carefully measures the circumference of my head to fit the special cap that will connect me to the fNIRS device measuring my brain activity. fNIRS, or functional near-infrared spectroscopy, basically measures the oxygen levels in the blood in my brain by sending light through the skull. Malina explains that when an area of the brain becomes more active, it needs more oxygenated blood. So the device reveals which area is activated.

As the experiment measures not only the activity of one but two brains, the process is called fNIRS-hyperscanning. It allows researchers to investigate two brains simultaneously.

Banker and follower

Once the cap is in place, Lea and I move into a separate room. We sit down at a table facing each other, with keyboards in front of us; a divider obscures our view of each other’s hands. On my left, there are two screens, but only one is directed at me. On my right is the fNIRS-hyperscanning device.

Attaching the ‘optodes’ to their designated holes, Malina connects the cap to the device, which spawns dozens of tangled wires.

Then, she leaves the room, and everything quiets down. For the next one and a half hours, we silently play a simple poker game; there is only the occasional clicking of keys. I become the banker for four rounds, Lea the follower. After a short break, the roles switch.

Call or fold

Each round has thirty trials where the screen shows the banker whether they have a high or low card. They then decide whether to bet or fold by clicking specific keys. The follower observes the banker’s decision and can either call or fold.

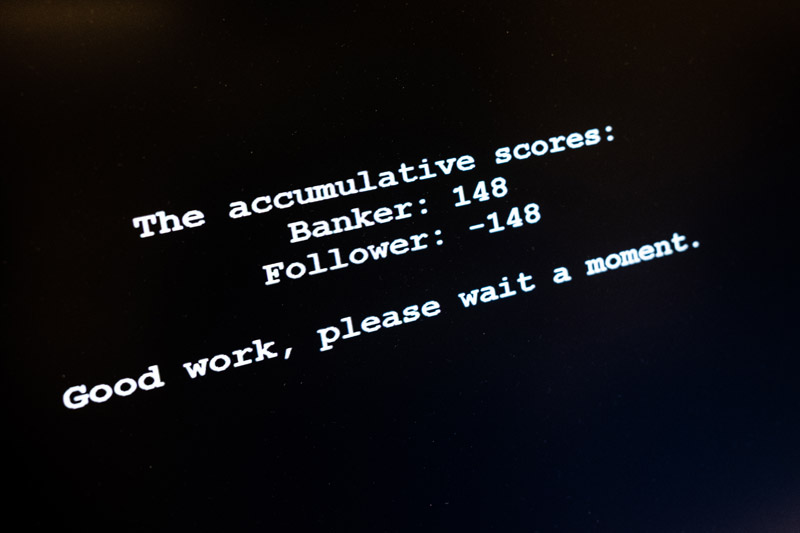

If the banker bets a high card and the follower calls, the banker wins, and the follower loses 18 points. If the banker bets a low card and the follower calls, the points are reversed. If either player folds, they lose two points, and the other wins two.

As the banker, I try various bluffing strategies, feeling thrilled when my bluffs don’t get called… Today isn’t about winning or losing, so I’m enjoying this rather serene mind game of betting and folding.

I even feel proud to learn afterwards that my performance as the banker was good, with a high score, and I didn’t do too poorly as a follower either. It makes me curious for the results of this study, which the researchers expect to publish around autumn.

- Faculty: Medical Sciences

- Duration: about two hours

- Remuneration: 4 credits