Guinea pigs #9Watching a stressful movie

‘I feel disgust, grief, pity, sadness’

Watching disturbing movie scenes isn’t something you just do – at least, not when you’re participating in a psychology study. First, I’m informed about the experiment and I have to explicitly consent to continue. Then, I have to fill out a questionnaire so the researchers can determine whether I’m mentally healthy and therefore eligible to participate.

The research project I came for at the Heymans building explores the effects of distressing graphic content on healthy university students. ‘We assess how often participants think back on the film and whether the tasks performed after watching it have an effect on whether or not they experience flashbacks in the subsequent week’, third-year student Janina Tessmann explains to me.

I go through several questions about my well-being, how I have been feeling in the past week, and whether I suffer from any depressive symptoms. It takes around ten minutes. Good news: I can proceed to the second part of the experiment, Janina tells me after checking my score.

Computer game

I’m asked to play a game of Tetris. I’m confused, but curious as well: why are they having me play a computer game?I haven’t played Tetris in a long time and I fail badly at it. Just when I want to avenge my first bad run, the timer runs out and Janina comes in for the next step.

‘You’ll complete some rating scales about your mood. Then, you will watch a twelve-minute film consisting of several scenes of acted or real-life footage’, Janina tells me. They contain blood, serious injury, explicit physical and sexual violence, and death and may cause distress, she goes on. ‘Try not to look away. Imagine that you’re there, witnessing the events. If it gets too much, you can stop at any moment and you can ask me to come in.’

She turns off the light and shuts the door behind her, leaving the room pitch black. I start to feel slightly stressed. I breathe in and exhale slowly, to let out the heaviness in my beating heart. Then, I put my headphones on and press play.

Car crash

The first video shows an unusual car crash. The vehicle goes off the road and flies over a group of kids playing in a circle. I almost look away, but I try to stay focused, to keep my eyes on the screen. I only frown and wait for the next scene.

There are some scenes that I recognise from movies or series I’ve watched: The Revenant, Gone Girl, 13 Reasons Why. Still, rewatching them gives me an uncomfortable feeling in my stomach. The expressions on my face change from scene to scene: disgust, grief, pity, sadness. I see myself there and I put myself in the shoes of the victims of those events. It feels raw. It feels horrible.

During those gruelling twelve minutes, I keep asking myself: How can some people reach those situations in life where they act so ghastly? How can they be so remorseless? I cannot relate at all and I hope I never will.

Replication

As with many psychology experiments, participants can’t know the exact goal of the research, or it will skew the results. But as Ineke Wessel, the associate professor at psychology who heads up the study, explains to me later, the movie is a substitute for a traumatic event.

‘This is a replication of a 2009 study, which showed that playing Tetris can help prevent people from developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder’, she says. ‘But of course, we can’t expose people to a real traumatic event, that would be unethical.’

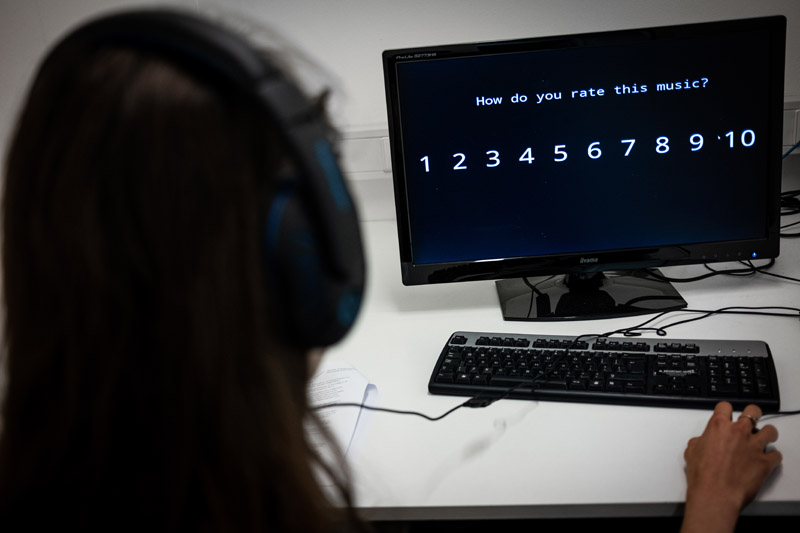

Afterwards, I fill out another set of rating scales about the film and my mood and then, I listen to fifteen excerpts of classical music, which I have to rate. ‘The scales were meant to reactivate the memories, while the classical music was a filler task, to distract you for a while and let the memory of the film settle in’, explains Ineke.

Finally, I play a game for about ten minutes where a red dot appears in the middle of the screen every now and then. The time passes slowly and my brain keeps getting distracted by some of the scenes I’ve just watched. Every time that happens, I try to shake off the visual memory and focus on the task.

Intrusive memories

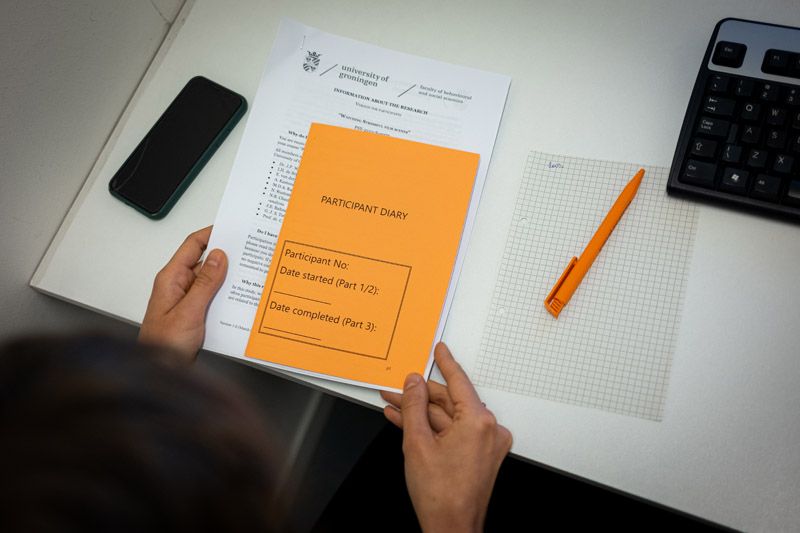

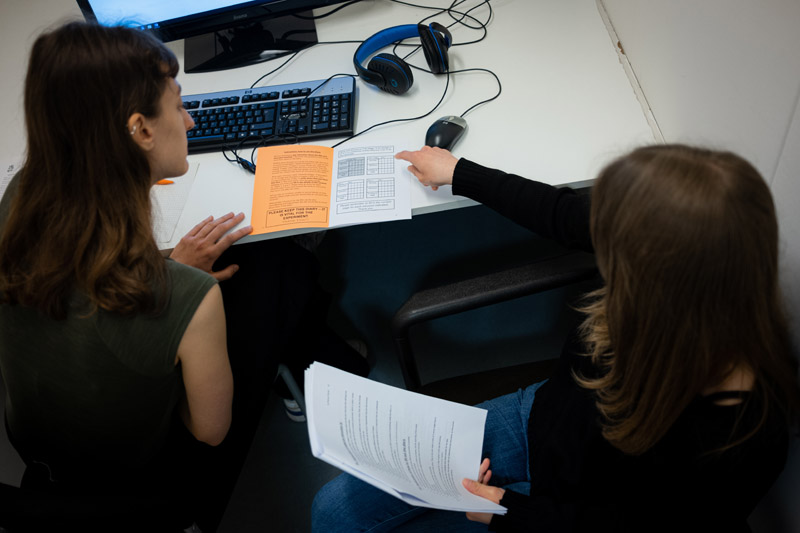

Janina then hands me an orange booklet entitled ‘Participant Diary’. My homework is to note down any intrusive memories of the movie that pop up in my mind, be it verbal thoughts or mental images, and describe them in great detail.

One week later, I’ve only experienced two intrusions. One came up in the afternoon as a combination between an image and a thought and the second arose in the morning two days after watching the film, in the form of a mental picture.

Janina and I meet up again. I give her my diary and immediately dive into a series of questionnaires about the film, what kind of person I am and how I deal with stress.

Skewed data

With that, the experiment is over, and Wessel can at last tell me what it was all about. The data from the 2009 Tetris study were ‘quite skewed’, she says. ‘That’s because the study had a small sample. With data like that, one or a few high values can have quite an impact on the results.’

Now, they are replicating it on an international scale, ‘in a large sample and in a slightly different context’, by collaborating with universities in the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Australia. ‘We are aiming for 432 participants in total.’

One thing I’m still wondering about is why I had to play the game with the red dot after watching the movie. ‘As the allocation was done randomly by a computer program, you ended up as part of the control group’, explains Wessel. ‘In the challenge group, they would play another game of Tetris immediately afterwards.’

The method they are studying is already being used in clinics for PTSD, but they hope to shine more light on the robustness of this effect. ‘This is only the start, though’, says Wessel. ‘There is still a lot of research we have to do, especially with patients.’

- Faculty: Behavioural and Social Sciences

- Duration: A two-hour session and a one-hour session, plus a week of keeping a diary

- Remuneration: none