Guinea pigs #3Brain stimulation to improve cognition

‘Anything for science, right?’

As we get older our thinking, our ability to process the world around us, to plan and take action – in short, our cognition – begins to fade. Neuroscientist Branislava Ćurčić-Blake, lead investigator in the CogMax-team, tries to find out whether life for people with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), a preliminary stage of dementia, can be improved with weak electrical stimuli delivered to the brain.

Today, I am one of her test subjects and I’ll be undergoing several neuropsychological tests.

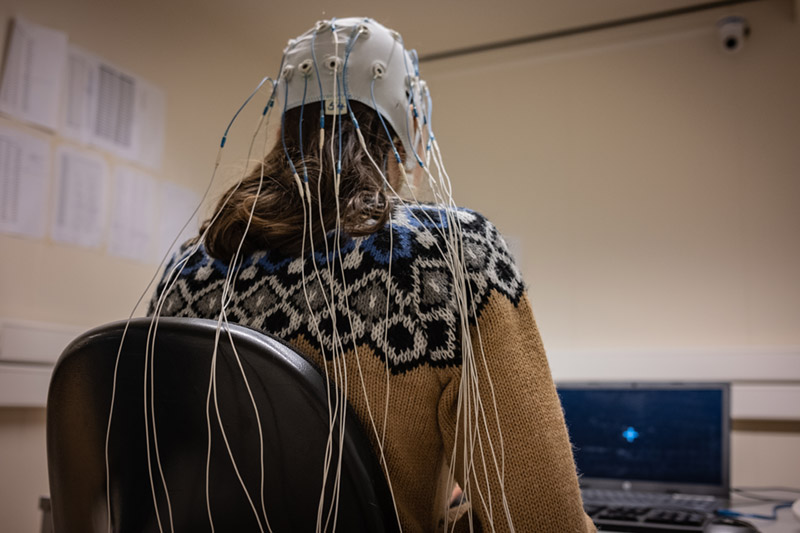

Nido Wardana, a PhD student in Ćurčić’s group, guides me down to a room on an underground level at the UMCG where a chair awaits me. He and Lotte Nijs, an internship student, measure my head circumference and height, so they can pick the EEG cap that fits my head.

Nothing has happened yet, but already my heart is beating slightly faster than usual. It is more out of excitement than fear, though. Fortunately, Nido and Lotte take time to talk me through all the steps, soothing away the stress.

Memory problems

If you have MCI, you have memory problems and difficulty performing multiple tasks at the same time, like simultaneously walking and talking with a friend. Today, according to Alzheimer Nederland, there are about 290,000 people battling dementia in the Netherlands. ‘And that means there are significantly more people with MCI’, says Ćurčić-Blake.

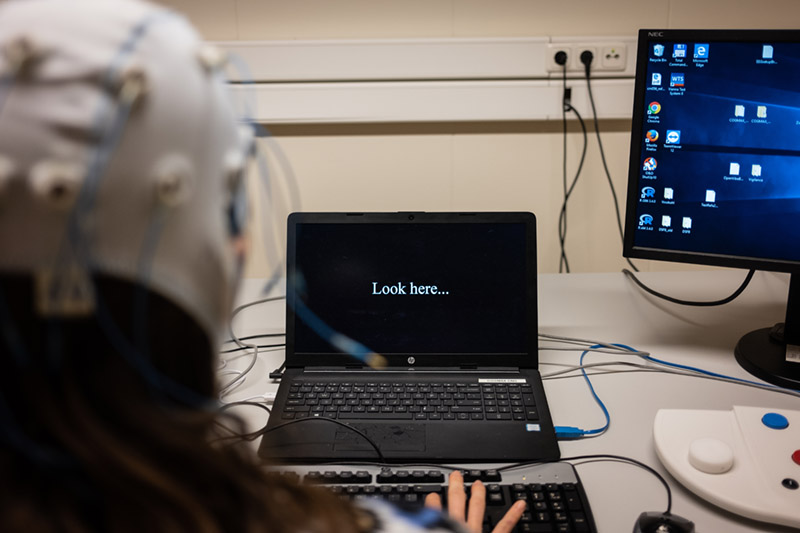

We go to an adjacent room, where I see a laptop, a monitor, and both a normal keyboard and a special one. On the wall, a webcam is monitoring me. Behind me there is an offensive amount of white cables. They are meant to plug into the EEG cap, I gather.

But I begin cap-less: the vigilance of my working memory will be put to the test. On the screen I see a plus sign. My task is to press a tab on the keyboard as soon as I see it change into an x. It takes ten slow minutes.

Electrodes

Then, the fun part kicks off. Nido and Lotte casually carry in the EEG cap, some gels, and filled syringes with long sterilised IV needles. My eyes move towards the monitor, where each electrode is shown. They are now inactive. ‘We’ll fill those with a highly conductive electrolytic gel, because it helps to acquire good contact and reduce the impedance of the skin-electrode interface’, Nido says.

It takes longer than they are used to, because I have a lot of hair, he explains. ‘Most of the participants in the study are elderly people.’

The electrodes fluctuate on the screen as they are filled with gel. Thirty minutes have passed by already. ‘I will just come to this electrode later. I need a win’, laughs Lotte, as she patiently tries to pierce the electrode with the IV needle and let the gel flow through.

Yellow circles

When the EEG cap is finally set, I get headphones and the special keyboard is placed in front of me. The application on the computer is, surprisingly, set up in my native language, Romanian, which makes reading the instructions easy.

A black circle appears on the screen. Every time it is filled with a bright yellow, I need to press a black rectangular tab. Next up, a second black circle appears that is sometimes filled red. My only task now is to press the same tab when the yellow circle shows up in unison with a beep sound. This way, they test how fast my brain processes information.

I feel a slight tingling. That must be the electrical current, I think, but no: ‘It’s a placebo, because you are not actually part of the study’, Ćurčić-Blake explains. ‘You feel the same regardless of whether you receive real or sham stimulation, though.’

The weak electrical current that is used on real participants with MCI ‘increases the excitability of the neurons in the brain and forces them to work at the same rhythm’, says Ćurčić-Blake. The procedure is not painful and presents little to no side effects.

Wet look

For the final test, I have to tell if a sequence of letters, numbers and symbols are correct. This is meant to improve both my processing speed and working memory. Then the session comes to an end and my EEG cap is taken off. My hair is full of gel and it looks like I spent some time on a ‘wet look’ hairstyle. Anything for science, though, right?

Actual participants spend a lot more time on this study than I did. They have twelve days of doing all kinds of neurological tests, including an MRI, plus a follow-up appointment after one month and another one after a year.

That should net them more than just the monetary remuneration, though: Ćurčić-Blake expects that when they get back for those final experiments, their dementia symptoms will have decreased and their cognitive function is improved. And that’s worth a little time.

- Study: CogMax (applicants over fifty with cognitive issues welcome)

- Duration: 3 hours; actual participants have 14 appointments over one year

- Remuneration: 100 euros for the entire study