UG pharmacists working around the clock

There might already be a treatment

He’s all alone in the giant laboratory at the Antonius Deusinglaan. No one else is allowed inside, but the normal rules don’t apply to pharmaceutical technology researcher Paul Hagedoorn. He is working on a potential treatment for the coronavirus that currently has the world in an iron grip. ‘This might change everything’, he says, and he’s not exaggerating.

He emphasizes: it is not a new, but an existing medicine. The difference is an inhaler. And it is not at all sure that it works.

It started a little over a week and a half ago, when Hagedoorn got a phone call from pharmaceutical professor Erik Frijlink. The latter had read about two types of drug to combat malaria, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which might work against the coronavirus everyone was so scared of. ‘It has shown positive effects on a cellular level’, says Hagedoorn.

Scientists haven’t yet been able to explain the effects. It’s possible that, upon administering, the substance is transformed into a positively charged particle that remains in the cell for a longer period of time, thereby blocking the virus from entering the cell. ‘There are some other explanations, though.’

Do not disturb

But, said Frijlink, what if we find a way to administer this drug to patients in the fastest, most effective manner?

Leave Paul alone and do not disturb him

Hagedoorn and Frijlink have worked together before. They develop special inhalers that administer medication as effectively as possible. They made inhalers for asthma and COPD, as well as diseases in which the use of an inhaler might be less obvious, like Parkinson and TBC Wouldn’t an inhaler be perfect to combat a virus like COVID-19? ‘You’d deliver the medication straight to where you want it to be’, says Hagedoorn. ‘Which is the lungs.’

The idea turned Hagedoorn’s life upside down. He ordered the necessary resources, which fortunately were delivered to his lab the next day. He cancelled any and all existing appointments. His colleagues, who were still at work since the building hadn’t been shut down, were told to ‘Leave Paul alone and do not disturb him under any circumstance.’ Hagedoorn focused all his energy on the new project.

Grain of sugar

He explains you can’t just administer chloroquine straight to the lungs. First, you have to make sure its particles are absolutely minuscule. ‘Like a grain of sugar that has to cut into 25 million particles’, says Hagedoorn. ‘That’s how small the particles should be.’

That’s not an easy task. Hagedoorn puts his raw materials in a kind of mill and connects a hose pumping nitrogen into the mill. The particles collide with each other under the high pressure, breaking apart. ‘I catch them and use a laser to check whether they’re the correct size’, he says.

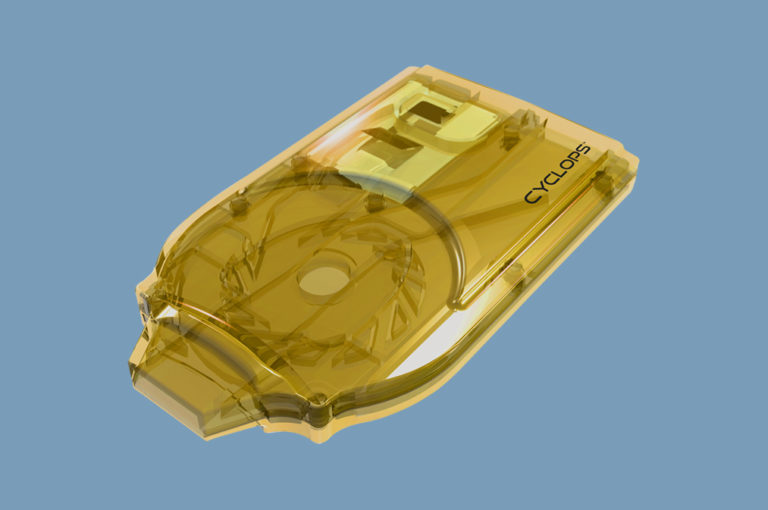

The particles, which have been treated with additives so they don’t end up clumping back together, are then put into a special inhaler, called the cyclops, which Frijlink and Hagedoorn invented and patented. They use a simulator that mimics a person inhaling the medication to see if the drug can penetrate the lungs deeply enough.

Potential

Now, only a week and a half after Frijlink first picked up the phone, they’ve done it. They’ve created a treatment that might just work, as well as an inhaler that can administer the drug. ‘It’s bizarre’, says Hagedoorn, clearly a bit overwhelmed. ‘This would normally take a year. And we did it in a week.’

This would normally take a year. And we did it in a week

Sure, he has experience; he’s been doing this for 27 years, so he knows how the process works. He had help from PhD candidate Imco Sibum and post-doc Floris Grasmeijer. The doctors, including Onno Akkerman at the UMCG, are doing everything they can to facilitate his work. ‘That is great. They’ve really recognised the drug’s potential.’

The medical ethical testing committee (METC) has also done everything it could in light of the emergency. ‘They’re trying to make sure the administrative side gets handled as quickly as possible.’

Healthy subjects

Now they have to test the substance on healthy subjects. Animal tests won’t be necessary, since it involves existing medication that’s being administered in a different way than it normally would.

Hagedoorn, who just finished a video conference with the whole team, says the protocols are currently being written. They’ve established how the trials will go. The METC will evaluate as quickly as possible. In an ‘ideal scenario’, the first tests can be done in four weeks.

It’s likely these tests will be performed on a dozen healthy healthcare workers, says Hagedoorn. He and Frijlink hopes their drug doesn’t just cure the virus, but also protects people from it. And it’s just right there, on his desk. Ready to go. ‘We’ll administer a relatively low dosage at first, and then slowly increase it’, he explains. They’ll check the subjects’ lung function and take blood.

‘If everything is satisfactory, we could start using it on real patients soon’, he says. He’ll certainly beat his international colleagues looking for a solution. ‘They’re looking for vaccines and antibodies’, he says. ‘It’s taking them much longer to develop those.’