Students say #MeToo

Sexual violence is not normal

‘Let’s make one thing clear: sexual harassment and violence are never acceptable’, said rector magnificus Elmer Sterken in response to the UKrant’s survey, which showed that many students experience harassment and sexually transgressive behaviour. His message is clear, but it doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality of many students.

222 students reported sexually transgressive behaviour to the UKrant. Their experiences range from sexually charged remarks or dance floor groping to stalking, intimidation, or rape (98 students reported experiencing the latter three). And the majority of these students deal with the behaviour Sterken calls ‘never acceptable’ by simply accepting it.

The MeToo movement that reached a fever pitch in 2017 made one thing clear: it’s time for society to fight sexual harassment. Sterken clearly agrees. But what does that actually look like?

Camera footage

Many of the students who filled out our survey weren’t quite sure what to make of their personal experiences. They often downplayed the violation: it only happened during social events; it could happen to anyone; their ‘no’ hadn’t been assertive enough.

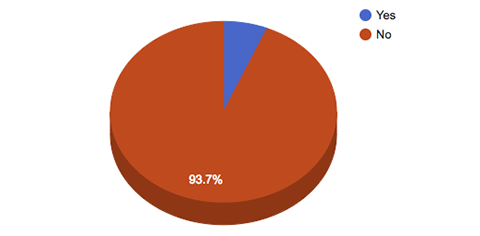

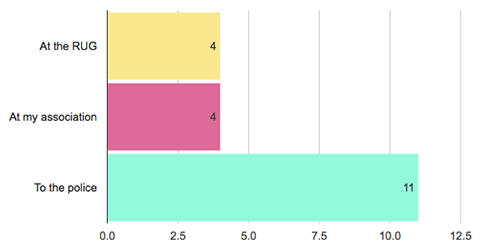

Only fourteen respondents eventually went to their association, the RUG, or the police. And only eight of those who had been stalked, intimidated, or raped had ever talked about or reported their experiences to someone else.

Did you report your experiences?

Where did you report your experiences?

‘Students don’t come to us very often’, says Jos Dekker, who serves on the vice police team for the northern Netherlands. ‘But we know there must be things going on in their world’, he says, because students drink, do drugs, and go out at a higher rate than other demographics. ‘And we’ve seen the camera footage from the city centre.’

Record

‘To be honest, students don’t come to us for much’, says student officer Petra Koops van ‘t Jagt. ‘They don’t even report stolen bikes.’ But why not? The officers don’t know – and they wish things were different; the police need to know what’s actually going on in the city. ‘That way, we can record it’, explains student officer Edwin Valkema.

Why Sanne didn’t report her rape

Marjolein Renker, independent confidential adviser at the RUG, doesn’t hear from many students either. In all of 2018, only thirty students visited her office, eight of whom because they had experienced sexual harassment.

Please confront people when they’re doing something that’s not okay

In the UKrant survey, eleven students reported having an uncomfortable experience involving a RUG lecturer in the past five years. Only one her lecturer’s behaviour to the RUG. The other ten kept quiet, including two students who suffered pushy advances, stalking, or intimidation. They wouldn’t tell the UKrant who the perpetrators were:

‘Sorry’, one of them writes. ‘But there’s a reason I never reported him. I don’t feel safe enough to speak out and I’m not sure it would actually accomplish anything.’ She reported that someone else recently made a complaint about the same lecturer. ‘He got a slap on the wrist, but nothing changed. He’s treated other students inappropriately, but no one dares to speak up.’

Fear

Renker calls the student’s story ‘ghastly’. ‘It looks like the people in charge didn’t take any action. Although there is the possibility that the man was disciplined behind closed doors, which means the students wouldn’t know anything about it.’

She knows that people can be afraid to speak out: ‘Students have an interdependent relationship with their lecturers. If a student accuses someone by name, both sides of the story will be investigated. Students don’t want to take that risk, because they’re afraid the lecturer will give them a negative assessment at the end of the semester.’ Renker says students who make a complaint against a lecturer will never be assessed by that person. ‘But I’ve been unable to assuage their fear.’

Like the police, Renker wishes students would break their silence. ‘The more reports I get, the more I can do.’ She’d really like it if people talked more about unwanted behaviour – not just with her, but with each other as well. ‘Not talking about it can ultimately normalise it.’

Talk about it

In her role as confidential adviser for a little over a year, she has seen first-hand how people tend to ignore or bury unpleasant experiences. ‘That does annoy me sometimes. Please don’t keep it in; talk about it. And please confront people when they’re doing something that’s not okay.’

And don’t dismiss your own feelings either, Renker urge. She notices that people come to her seeking some degree of validation for their feelings. ‘They e-mail me asking whether it’s normal that they think something isn’t normal. In that case, someone went through something they didn’t like, but they’re afraid they might be overreacting.’

Which is exactly why RUG alumna Gabrielle* never used to protest when guys in town or in her association, Albertus Magnus, catcalled her. But these days she finds herself unable to stay silent. ‘I think it’s because it’s in the media so much these days. And because I was raped.’

Normal

Gabrielle was raped while travelling in Colombia, but the experience made her Groningen in a different light when she returned. ‘I think sexual harassment is a big problem in Groningen. The “less serious” offences are par for the course these days. People think it’s normal.’

I don’t think sexually transgressive behaviour is much of an issue here

We need to educate people about what constitutes sexually transgressive behaviour, Gabrielle says. ‘Men – or women for that matter – often don’t realise what they’re doing, because the difference between an innocent remark and offensive action can be really vague. The university should do more to raise awareness.’

In the wake of the UKrant survey, the RUG is already putting plans in motion, says Sterken, and will ‘earnestly start working on the issue’. He wants to set up a campaign with and for students. ‘I want to lift the taboo by issuing a zero-tolerance statement, improving function on our websites for reporting transgressive behaviour and abuses, and providing active bystander training.’

How do I help a loved one who’s faced assault?

Action

After she’d been drugged and raped as a first-year student several years ago, Sofía wanted to take action as well. ‘I wrote a Facebook post about what had happened to me. Eleven other girls sent me messages about similar experiences. Eight were first-year students, like me.’ She concluded that Groningen students needed to be taught what constitutes transgressive behaviour.

How the confidential adviser can help

Students and staff who experience unwanted behaviour at the RUG can talk to Marjolein Renker. Renker doesn’t answer to anyone; not to a boss, not to colleagues. Her only superiors are the board of directors, but they have no say in how she operates. So she is completely independent.

‘If you come to me, you are in charge; you decide what you want to happen’, she emphasises. Meetings are always confidential and no one has to make a formal complaint if they don’t want to. But if they do, Renker can help them explore their options. She can then forward the complaint to the perpetrator’s managers. The complaint will be weighed during an assessment, and in extreme cases, could lead to termination.

If you don’t want your lecturer to know anyting, you can make a confidential complaint; no one but the confidential advisor will know who filed it. ‘That does make processing the complaint more difficult, because we only get one side of the story’, says Renker. But it is still worth doing: ‘the more complaints I get, the more I can do.’

If the perpetrator was a student, you can talk to the confidential adviser about that as well. ‘In that case, we’ll see if there’s anything the faculty or the department can do.’

So Sofía started a campaign with the support of friends from her faculty. ‘We were willing to do all the work ourselves, even use our own funds. We just felt that getting support from the RUG would help with PR.’ She booked an appointment with then-confidential-advisor Marijke Dam.

‘Do you know what she said?’ Sofía asks. ‘She said: “I don’t think sexually transgressive behaviour is much of an issue here.” Because she hadn’t heard much about it.’ Then and now, Sofía is astonished and hurt by the brush-off. ‘I told her exactly what had happened to me, and what I’d seen happening in clubs like Kokomo, and she just didn’t do anything with that at all.’

Black and white

Marijke Dam remembers that meeting as well. ‘She came in with a campaign idea, but I didn’t like the approach of the campaign. That’s why I didn’t support it.’

What was wrong with Sofía’s approach? Dam searches for the right words. ‘Her angle was that when it comes to sexual harassment, the perpetrator is always the only one who’s responsible. I thought that was too black and white.’

Dam doesn’t want to blame victims, ‘but if you expect everyone to treat you with respect, you make yourself vulnerable. When you’re in a bad neighbourhood, you have to be careful. You have to keep an eye on your drink in the club. I know: it’s ridiculous how much we have to do to ensure we’re safe.’ But that’s the world we live in, she says.

But that doesn’t answer the question of why she had a problem with a campaign aimed at perpetrators and not victims. ‘I didn’t see the need, based on the kind of reports I’d heard, and based on her story’, says Dam. ‘I told her clearly that I was not the person she needed to talk to about the campaign. She should have gone to the public relations department, or the dean of her faculty.’

Panic attacks

In an institution as large and complex as the RUG, it’s not always clear who can help. Sometimes, no one can. Student Valerie was stalked and eventually raped by an older guy she knew at the university. Soon after she began to suffer from panic attacks, became increasingly claustrophobic, and was easily startled by loud noises.

Things got so bad that Valerie eventually went to the student psychologist. Did it help? ‘She did take me seriously, so that was good. But she clearly had no idea what to do with me.’ Besides, Valerie’s problems weren’t just caused by what had happened; she was also afraid of what could happen. Her rapist continued to study in her faculty. She could run into him anytime, anywhere: in the halls, cafeteria, the elevator.

‘I talked to my student advisor about that’, says Valerie. ‘He said that I could see the concierge at the faculty if I saw him. That they would keep an eye out.’ She’s silent for a moment. ‘Fortunately, my rapist has since moved to Canada.’

Limits

There are limits to what the RUG can do, says Renker. ‘Sometimes it just isn’t simple. The other student has just as much of a right to be here. The university can’t just tell them they’re not allowed at the faculty anymore.’

They advised against reporting it. And they told me I should have said “no” more clearly

When Valerie went to the police several months after her rape, they couldn’t do much for her either. Anything evidence – traces on her body, DNA – was long gone. ‘They advised against reporting it. They also told me I should have said “no” more clearly.’

Invitation

Student Larissa Jellema recalls her own encounter with the police with a grimace. ‘Let me put it this way: I know they meant well, but I would have liked to be treated better.’

Larissa having drinks downtown with an acquaintance when she started feeling unwell. She wanted to go home, but had to go to his house first to retrieve her bicycle. She went up to his bathroom to vomit, which he somehow took as a sign to drag her into his bed and rape her.

Like many other victims, she wondered if she were to blame somehow. Shame silenced her; she didn’t talk about the assault. ‘I was afraid people would ask why I hadn’t come forward about it sooner.’ But in the eventually, she went to the police for help.

Evidence

Without evidence, she couldn’t actually report her rapist. The police could only make a note of what she said had happened. Larissa knew was not surprised by that. But she was surprised by the way the officers treated her. ‘We were talking about any physical evidence and they made remarks like “for all we know you did it to yourself”.’

Vice officers have to be both empathic and critical, says vice officer Dekker. ‘We always give someone the benefit of the doubt, we don’t blame anyone for anything, and we always explain why we ask the questions we do.’ But the questions are hard: ‘what is the limit of acceptable behaviour? How did you communicate what your limits are? I’ve met people who I felt could benefit from assertiveness training. That’s the fine line we’re walking here.’

The most people who come here are honest. But it did shock me

Larissa thinks that’s exactly the wrong approach. ‘I don’t think the criminal justice system in the Netherlands gets it right. In the UK, the courts look at consent; have both parties consented to the sex of their own free will, and are they both capable of making that choice?’ If one of the two hasn’t freely consented or isn’t capable of doing so, the sex was not consensual and other person is punishable by law. ‘In the Netherlands, the definitions are so specific that as a result, perpetrators are better protected than victims, really.’

How the police can help

Assault and rape are punishable offences. This means you can report them to the police and ask them to investigate. The police will then collect information and evidence. It may be very difficult, but in cases of sexual violence you have to report it as quickly as possible to secure DNA evidence. ‘You have a window of approximately one-week after the rape’, says Dekker.

Street harassment such as catcalling isn’t a punishable offence in Groningen, but you can ask the police to make a note of it. You can file a statement even when you don’t know who has harassed you and can’t prove anything. Your statement can help the police in later investigations, and if they receive many statements about a certain area where harassment happens often, they can assign a patrol.

You can indicate whether you’d rather talk to a male or a female officer. If you don’t speak Dutch, they’ll get you an interpreter.

But Dekker says both victim and alleged suspects need protection. Because some people lie about rape.

Exception

Marjolein Renker says she once received a false sexual harassment complaint. ‘It turned out to be from students who wanted to get a lecturer fired.’ She emphasises that cases like that are exceptional: ‘Most people who come here are honest. But it did shock me.’

Sometimes, sexual violence can be defined clearly. But there are also times when it isn’t clear who is a victim and who is a perpetrator, or what ‘justice’ should even look like. Sometimes, victims don’t want justice at all – they want peace. Sometimes, perpetrators have no idea what they did wrong. Sometimes, an innocent person can look like a perpetrator and a perpetrator can look like the victim. How do tackle something so varied, so complex, and so – as one student wrote on our survey – ‘normal’?

There’s only one thing everyone, from vice agents to students, agree on: we have to talk about it. Talk about it with law enforcement, so they know what they’re up against. Talk about it with counsellors, so they can help. Talk about it with each other, so we can learn where the boundaries of acceptable behaviour really lie. If we want to prevent sexually transgressive behaviour, we have to keep telling each other that it’s not normal.

How do we fight sexual assault?

For privacy reasons, the names of Sanne, Valerie, Gabrielle and Sofía are fictional. Mareike didn’t want us to publish her last name. Their real names are known to the editorial staff.

This was part two in a two-part story about sexual transgressions.