RUG students say #MeToo

Raped in your own bed

Me too. It was once a neutral phrase. But then it became a hashtag, and then it became a movement: ‘MeToo’ was a way to combat sexual violence with candour. Not long after, MeToo became a buzzword that everyone knew but that often lacked impact. It was easily co-opted into a joke: ‘Take it easy at the New Year’s reception, you don’t want to become another MeToo.’ ‘You can’t even look at a girl or she’s all like “Hashtag MeToo”.’

But for RUG student Floor Bakker, MeToo is no joke. It represents the time a fellow student forced his way into her house and raped her.

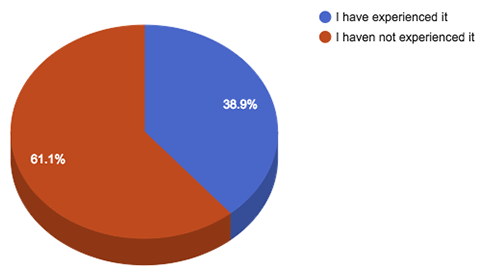

Research done by UKrant (see box) shows that students in Groningen experience varying degrees of sexual intimidation and sexual violence. We asked approximately six hundred students if they have ever experienced sexually transgressive behaviour; forty percent said yes.

#metoo experiences

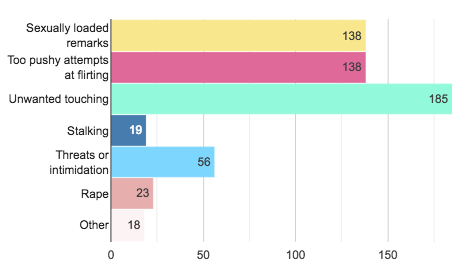

Most of the time that behaviour is unwanted touching, sexually charged remarks, or pushy advances. But approximately 44 percent of the students have experienced intimidation, stalking, or rape.

Type of experiences

Floor

Three years ago, Floor became friends with a guy who studied at her faculty. He was a little older than she was. They got along well. ‘We helped each other with assignments, met up at each other’s houses.’ But after a while, their friendship changed. He wanted more. Floor didn’t.

One evening, the study buddies agreed to meet at his house. Floor entered his room to discover that every single wall was covered in pictures of her. He got down on one knee and asked her to marry him.

She broke off contact. But he started bombarding her with Facebook messages. He wanted to know why he wasn’t good enough, begged for another chance, threatened to kill himself if she didn’t give in. She didn’t give in.

‘And that’s when he showed up on my doorstep’, she says, her voice low. ‘He forced his way in. He raped me. In my bedroom.’

Someone you know

When we think of rape our minds often jump to the cliché image: a creepy, violent guy jumps out of the bushes in the dark. Not to a faculty friend, our own bed, our own room.

But most rapists are actually known to the victim, according to numbers from sexual expertise centre Rutgers, published in 2017. And in 64 percent of the cases reported in the UKrant survey, the perpetrator was a familiar person. In fact, most of them were fellow association members.

Sanne

At the start of the 2017-2018 academic year, Sanne* joined her programme’s study association and attended their introductory camp. ‘There, a guy had sex with me against my will. I didn’t want to have sex with him, I told him no, but he did it anyway.’ Afterwards, he told her it was the alcohol. That he thought she wanted it too.

Sanne tried to pretend she was fine. ‘I just tried to not think about it.’ Camp ended, and she started going to class and parties; everything a normal first-year student does. But her rapist was doing all those things as well. One day in class, she felt him watching her. ‘I though, I have to get out of here.’

Mareike

Panic. American-German student Mareike knows all about it. In the summer of 2015, when she was seventeen years old, Mareike moved to Groningen. When an acquaintance offered to help her move her furniture into her new room, she happily accepted. Inside, he was suddenly on top of her.

It was all over in minutes; that’s how long it took him to finish. But for Mareike, it seems like it will never end.

Frozen

In addition to what a rapist does to you, your own body compound the trauma, explains clinical psychologist Judith Daniels, who studies post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) at the RUG. ‘The physical part of sexual arousal is simply biological.’ Without wanting to, women might get aroused, and men can still get erections even when they don’t want to have sex. According to the Centre for Sexual Violence (CSG), one in five people who have been raped or sexually assaulted experience this.

Victims can also suffer from dissociation: they freeze, can’t move, and can’t fight back. ‘All this can make them feel like they can’t trust their own body anymore’, says Daniels. CSG research shows that half of all rape victims felt ‘paralysed’.

Floor calls it ‘frozen’. That’s how her body felt when her stalker was raping her. ‘I told him I didn’t want to have sex with him, that I wanted him to leave, but I just couldn’t move.’ It wasn’t until her attacker tried to pull her towards him again that Floor’s muscles started behaving as they should. ‘That’s when I hit him.’

Just fine

Not all traumatic events result in PTSD, Daniels emphasises. ‘People can handle a lot more than they think. Approximately half of people who are raped get past it without developing a mental disorder. But the other half struggles: they are stressed, frightened, have trouble sleeping. They ruminate on the event and are desperate to avoid certain people, places, or situations.

The good news is you don’t have to live the rest of your life like this. ‘Therapy can help you manage PTSD’, says Daniels. But not if you continue to pretend like nothing has happened to you.

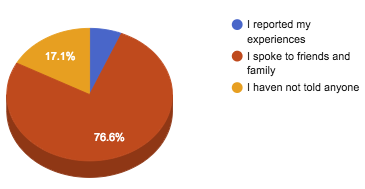

Most students who experience sexually transgressive behaviour end up talking about it to people. Seventy-seven percent of respondents talked to their friends or family. Only fourteen students – six percent of respondents – reported their experience to the RUG, their association, or the police.

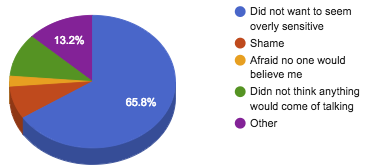

But 17 percent of respondents never told anyone about their experience. They were afraid people would think they were whining, they were ashamed of what had happened to them, they were scared that no one would believe them, they though no one would do anything about it.

Men were less likely to talk about their experience than women. Of all the students who said they had experienced sexually transgressive behaviour, twenty were men. Nine of them – nearly half – never told anyone about it.

What did you do after your experience?

Why didn’t you say anything?

Evan

Girls are never shy about letting RUG student Evan* know that he is easy to look at. Sometimes looking isn’t enough, and they actually touch him, like that one time he was cleaning up the room after a meeting with his fellow association members. Almost everyone else was gone. Suddenly he felt hands on his butt. It turned out to be a female fellow member.

‘It was a girl I got along with pretty well, so I told her off’, says Evan. ‘Your butt just looked so nice in those slacks’, she tried to justify herself. It was neither the first nor the last time someone would touch him without permission. ‘It happens a lot during drinks. I can remember someone slapped me on the butt once. Really hard, too. When I turned around I saw a group of girls running away laughing.’

These incidents really make Evan uncomfortable, but it isn’t easy to make other people understand why.

His friends would ‘say stuff like “hell yeah, get it”, or “man, I wish that would happen to me”.’ Was this sort of thing normal? He wondered. He couldn’t help but imagine how much worse it must be for women when they go out. Their experiences could be so much more extreme.

In the summer of 2017 he went with a girl from his board to an association boards event. She started ordering them both drinks in rapid succession, one shot after another. ‘I didn’t really want to, but I drank them all.’ He decided he would stop in time to get home before it was late.

But the last thing Evan remembers from that night is being pressured to chug a beer after breaking some obscure association rule. From that moment everything goes black until the moment he wakes up in his fellow board member’s bed. Naked. Anxious, he waits for her to wake up. What happened? Did they make out or something?

But it turns out they did quite a bit more than make out. ‘And’, the girl says, ‘I want to stop by the pharmacist for a morning-after pill.’

‘I was in shock for the rest of the day’, Evan recalls. ‘Everything was a blur. All I could think about was: what happened?’ He couldn’t remember, but he did know he was not a willing participant.

That’s when he got angry. Not just at her, but at himself. He knows he didn’t want to have sex with her, and he knows she knew it as well. ‘I know you don’t take your principles too seriously’, she told him by way of apology. And Evan also blamed himself. ‘I shouldn’t have been drinking so much. But I did.’

Guilt

Victims of sexual violence often react this way, says student psychologist Friederike Vieten at the Student Service Centre (SSC). ‘They come up with all sorts of things they should or shouldn’t have done. If only hadn’t been drinking so much, if only I hadn’t worn that skirt, etc.’

Guilt can also make it harder for people to face what happened. ‘Most people try really hard to pretend it never happened. But that almost never works.’

Sofía

Besides, says Spanish student Sofía*, that won’t help the cause. ‘We need to be talking about it. That’s why the #MeToo movement is so good’, she says. ‘There are too many people who don’t know what consent truly means, who don’t know where the line is and when it’s being crossed.’

Sofía should know: her own lines have been crossed many times over. There was the guy who wouldn’t stop talking about how important it was that girls enjoyed sex too – only to forget all about that when he wanted sex and Sofía didn’t. Or the date who, upon discovering Sofía was bisexual, pushed her down and hissed that she was a ‘dirty dyke’ and that he ‘would do her much better than a woman could’.

There was that drink in a club in Groningen that made her sleepy and sluggish after a few sips. Sofía was eighteen and had gone out with a group of students she’d only just met. ‘I hadn’t had much to drink at all, but suddenly I couldn’t hold myself up.’

All she can piece together from that night are disturbing snapshots, warped stills from a horror film. Snapshot: one of her acquaintances drags her into a toilet. Snapshot: her clothes are removed. Snapshot: he forces her to perform oral sex on him. Who does? Where? When she finally wakes up she is alone, on the toilet, naked.

For a long time, Sofía blamed herself. ‘It took me years to cut that out. People will judge you for so many things: whether you’re wearing the right clothes, how much you drink, whether or not you clearly said “no”, whether you struggled.’

After years of therapy, she has finally learned that none of these things can guarantee your safety. What’s important is your attitude towards this kind of behaviour: do you accept it as an unpleasant but unavoidable part of life? Or do you fight it?

Normal

Judging by the answers to our survey, many students decide to accept it. An ex-student from the Hanze University of Applied Sciences downplays her experiences of sexual intimidation by saying: ‘I suffered no long-lasting effects, it always happened when I was out on the town.’

‘I’m not sure when something can be labelled as transgressive behaviour’, a RUG student says. She’s been slapped on the butt by strangers, she says, and she’s been approached by pushy men who won’t leave her alone until a few ‘burly friends’ join her. ‘But that’s happened to everyone once or twice, right? And the only effect it had on me was that I learned how to talk back.’ Another respondent writes: ‘I think every single female student has come across a dude who won’t take “no” for an answer during a night out. Unfortunately, that’s normal.’

It seems like students consider sexually transgressive behaviour par for the course in nightlife. You want to go out for drinks and dancing? You’re going to have to accept people touching your breasts and butt. You might spend a large part of your evening saying ‘no’ to an inebriated stranger who just thinks you’re playing hard to get. And there’s a good chance that on your way home, someone will tell you your legs look good biking. Unfortunately, that’s normal.

But will it always be normal? Or will #MeToo usher in an age that refuses to normalise sexual violence, intimidation, boundary-crossing? How?

This was part one in a two-part story about sexual transgressions.

Part two: how can we make Groningen a safer place for students? →

*For privacy reasons, the names Sanne, Evan, and Sofía are fictional. Mareike didn’t want us to publish her last name. Their real names are known to the editorial staff.

Help

Who can help me when I’ve experienced sexually transgressive behaviour?

The Sexual Assault Center

This is a collaboration between hospitals, municipalities, and the police, especially for people who have recently been assaulted or raped. The centre provides immediate care, will keep tabs on how you’re doing, and can refer you to expert help if you need it. (0800-0188 (free of charge, 24 hours a day)

The Groningen Feminist Network

The GFN has set up the project Let’s Talk About Sex in an effort to improve people’s knowledge of sex, but they’re always willing to talk to people who’ve experienced something traumatising.

Studenten Service Centrum

Are you a RUG student? You can make an appointment with one of the student psychologists of the SSC. You can schedule an intake interview for free. You can have up to four follow-up appointments, or you can get a referral to regular mental health care professionals. ‘We can also tell you to see the confidential adviser’, says psychologist Friederieke Vieten.

Confidential adviser at the RUG

If you’ve had an unpleasant experience involving a fellow student or a staff member at the RUG, it’s a good idea to tell the independent confidential adviser, Marjolein Renker. You can do this informally if you want, but you can also make an official report.

About this research

UKrant created an online survey about people’s experiences with sexual intimidation, violence, and transgressive behaviour. We distributed the survey among RUG and Hanze students and alumni who graduation less than a year ago.

A total 0f 571 students filled in the questionnaire: 440 RUG students, 81 Hanze students, and 50 alumni. This is a fairly large sample, but doesn’t necessarily represent the entire student population. We didn’t approach random students, but waited for students to come to us, which means we have what is called a ‘convenience sample’. We also cannot be sure that each respondent was honest filling in the survey, since it was online and anonymous.

We shared the survey on our Facebook page and asked study, student, and sports associations for help. Several of these associations shared the survey with their members. We would like to thank:

- Studentassessor Kathelijne de Vrijer en studieverenigingenkoepel CFO

- GSR Aegir

- GSSV Donar

- GSVV Donitas

- GSZV De Golfbreker

- GSBV De Groene Uilen-Moestasj

- AGSR Gyas

- GSPV De Noordpole

- GSKV Northside Barbell

- Literair Dispuut Flanor

- HOST-IFES

- ESN Groningen

- Groningen Feminist Network

- FFJ Bernlef

- Gereformeerde Studentenvereniging (GSV)

- CSFR Yir’at’Adonai

- Navigators Studentenvereniging Groningen (NSG)