BSS’ own Hall of Fame

‘Professors are only human’

BSS received its own Heritage Room in January: A permanent, free exhibition on the history of social sciences at the RUG.

It is focused on the ten scientists who were most important to the faculty. All three disciplines – sociology, psychology, and pedagogical sciences – are represented.

Mineke van Essen and Tamara Leenhouts, who put the exhibition together, have collected as many of the professors’ items as possible. Some of them were already owned by the RUG, and others are on loan to the faculty, either from the University Museum or the professors’ families.

The exhibition is not just about scientific research, but also about the people behind it. That is why some of the professors’ personal possessions, such as a christening dress, are on display.

The RUG Heritage room is the first in Netherlands, at least in the field of social sciences. Van Essen expects there will be more. ‘Universities are becoming aware of the history they possess.’

Reading time: 6 minutes (1,064 words)

Imagine suddenly having to flee in such a rush that you do not even have time to pack a suitcase. Fortunately, laptops are exceedingly portable and provide access to all the knowledge you need. SmartCat is full of ebooks, Dropbox has all your notes, and Wikipedia can help you out with any names or dates you cannot think of.

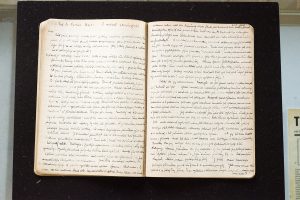

When Czech student Ivan Gadourek had to flee, it was 1948: there were no laptops and all his knowledge came from big, heavy books. But he simply could not leave without his intellectual luggage. He reached the Netherlands carrying eleven notebooks, filled cover to cover with excerpts and summaries of everything he had ever read. He went on to become one of the RUG’s greatest sociologists.

Gadourek’s story reads like a boys’ adventure book. And the Heritage Room at BSS has more stories like this. It is a permanent, free exhibition on over a century’s worth of history of social sciences at the RUG. It is the first time a Dutch BSS faculty has set up such an exhibition.

Ten protagonists

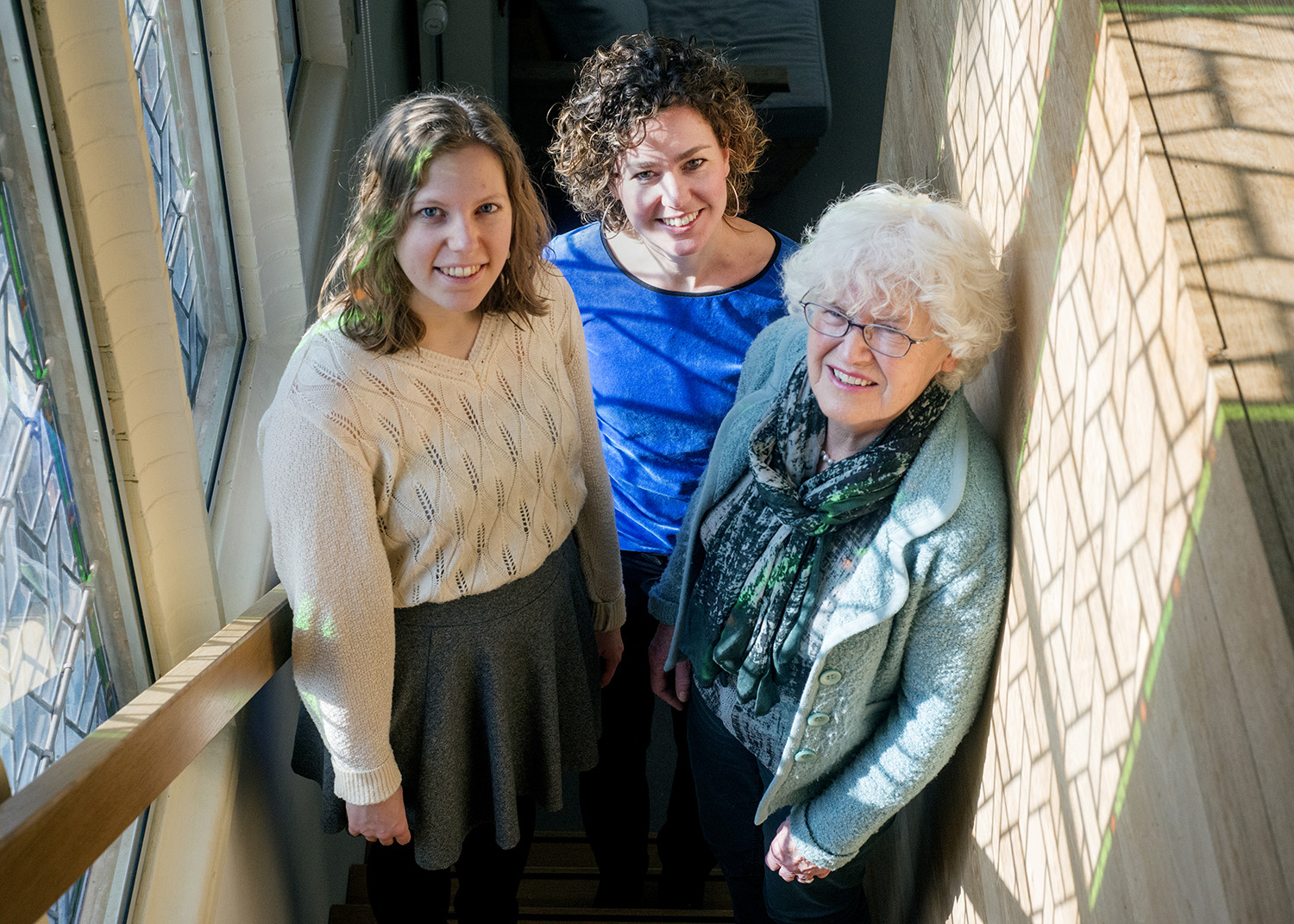

‘Whose shoulders do we stand on? That’s what it’s about’, Mineke van Essen says. Van Essen is an educational historian and a retired professor of gender studies, and she has written various books on the history of BSS in Groningen. She is joined by history student Tamara Leenhouts on the heritage committee. Carolien Lunenborg, who works as a pedagogical scientist at the faculty, also has a background in design and took care of the presentation.

‘It’s kind of a labyrinth around here’, Leenhouts says over her shoulder, climbing the wooden spiral staircase up to the Heritage Room. ‘Here’ is the Bouman building in the Grote Rozenstraat: a gorgeous BSS location with stained-glass windows, winding hallways, and complex patterns on the tiled floors.

The Heritage Room itself is high and long. Large pictures of the exhibition’s ten subjects grace the walls. Letters, possessions, and books representing their work and lives are displayed in glass cases.

Donations

Van Essen explains how they made the selection: ‘The faculty has three disciplines: sociology, pedagogical sciences, and psychology. We wanted to represent them proportionally in the exhibition.’ Three professors, ‘the founders of social science in Groningen’, were guaranteed a spot in the exhibition: psychologist Gerard Heymans, sociologist Helmuth Plessner, and pedagogical scientist and psychologist Henri Brugmans.

We also received a few things from the professors’ families. They were really open to it, which was extraordinary.

‘They are our three pre-war ‘big men’. After the war, interestingly enough, each discipline also featured a ‘big man’: Pieter Jan Bouman in sociology, Jan Snijders in psychology, and Hendrik Nieuwenhuis in pedagogical sciences. So that made six’, Van Essen says.

The last four professors were recommended by the various programmes at BSS. Psychology came up with Ben Kouwer, sociology nominated Gadourek, pedagogical sciences’ Wilhelmina Bladergroen got a spot, and educational theory sent Leon van Gelder.

Heritage on your screen

Would you like to know more about the professors and their work? The Heritage Room has a website with background information. It has video fragments showing former students and colleagues reminiscing about the top scientists. Van Gelder and Bladergroen can be seen in archive footage.

The exhibition curators collected everything they could get their hands on from these ten professors. ‘Some things the faculty already owned, but others we borrowed, from the University museum for example’, says Leenhouts. ‘We also received a few things from the professors’ families. They were really open to it, which was extraordinary.’

Gadourek’s daughter, for instance, gave Van Essen and Leenhouts one of the eleven notebooks he fled with. Hendrik Nieuwenhuis’ family lent them the pipe the professor liked to smoke, including the accompanying, strangely shaped ashtray. And thanks to the Bladergroen family, Wilhelmina’s christening dress has a prominent spot in the Heritage room. It has been folded carefully. Gossamer thin and bright white, it stands out among the books.

Charismatic characters

‘It’s part of the set-up of the room. We wanted more than just things related to scientific research; we wanted curiosities from the people behind the work’, Van Essen explains. ‘To show people that professors are only human, so to speak.’ The fact that they managed to get their hands on Bladergroen’s christening dress is like a cherry on top of the sundae: ‘She was an expert in the field of children and movement. So that fits in nicely.’

Bouman simply took his students on a bike ride into the countryside, struck up conversations with a couple of farmers and collected everything he heard in a book.

Van Essen can talk at length about every single professor in the Heritage Room. She effortlessly switches from fun facts about the musically inclined Kouwer (‘He went to the conservatory, too. Look, here’s a picture of when he was an opera singer.’) to anecdotes about the eccentric Bouman whose class she once took just to watch him speak.

‘That’s the kind of man he was. Everyone wanted to watch him speak. His classes were always packed.’ Gesturing to the portraits in the Heritage Room, Leenhouts adds: ‘I think that goes for all of them. They were charismatic characters.’

Were all professors scientific greats? ‘Heymans was certainly a pioneer in psychology. People still quote Plessner quite a bit. And Van Gelder is currently very topical because he is arguing that students shouldn’t have to decide which school they go to until they’re at least 15’, Van Essen says. ‘Obviously they’ve each left their mark, but they were mainly great in their own time periods.’

Chatting with farmers

Just like other research disciplines, the social sciences are not immune to progressive insights. Bouman, for example – the sociologist whose classes were so popular – employed research techniques that people nowadays would probably frown at.

Do you know what they found most interesting? That refugees can become professors.

‘He sent his students into the province to interview farmers and agricultural labourers about their living conditions’, Van Essen says. ‘A modern sociologist would prepare extensive questionnaires, draw up protocols, do statistical analyses.’ Chuckling: ‘The students biked through the countryside and struck up conversations with a couple of farmers, and Bouman collected everything he heard in a book.’

That everything was different in the olden days will surprise no one, but the Heritage Room really brings it to life. Reason enough for Van Essen to think that more of these projects will follow. ‘People are increasingly interested in scientific heritage. Universities are becoming more aware of the history they possess, realising that they need to treat it with care.’

Quite a number of people have found their way to the Groningen Heritage Room, including students and employees alike, both Dutch and international. ‘We’ve also got a few tours with high school students scheduled’, says Van Essen. ‘Do you know what they found most interesting?’ She stops by the glass case displaying Ivan Gadourek’s notebook. ‘That refugees can become professors.’

Tamara Leenhouts (left), Carolien Lunenborg (middle) and Mineke van Essen put together the exhibition in the Heritage Room at BSS.