Researchers on an expedition

Hunting for algae on the high seas

For thirty years, Dutch universities have used the research vessel Pelagia for all their marine-related research. When the ship was in need of a replacement, the question of whether there was any interest left in Dutch marine research. To find out, all Dutch seafaring researchers were given the opportunity to join the expedition.

On 11 December, the Netherlands Initiative Changing Oceans, the NICO expedition, left from Texel. It’s goal: a tour of the Atlantic Ocean, ending at the Azores.

The interest turned out to be huge. Almost all seafaring researchers in the Netherlands wanted to join. Groningen marine biologists Maria van Leeuwe and Jacqueline Stefels were also interested in the expedition, and together with approximately a hundred others, they signed up for the twelve-stage journey. The participants would be working on a total of forty research matters.

Earlier, Stefels and Van Leeuwe had spent five years in Antarctica to study phytoplankton, a type of alga that produces anti-greenhouse gases. Not all their questions had been answered fully, so this expedition was a golden opportunity. They jumped at the opportunity to be able to perform their tests in a completely different environment. They boarded the ship in the Bahamas, for its eighth leg to Ireland.

Anti-greenhouse gases

Because of climate change, understanding how these algae produce anti-greenhouse gases and under which circumstances they excel at this is important.

Stefels shows a map of the world on which each ocean has been marked with its own colour, depending on how much anti-greenhouse gas is produced in each one. But the map also shows quite a few white spots, which still lack data. ‘So the data set needs extra information’, says Van Leeuwe.

There are also areas with very little algae that still produce a relatively large amount of anti-greenhouse gas. To understand that paradox, it’s good to understand how these algae actually work. How much CO2 do the algae take in, how much anti-greenhouse gas do they produce, and what factors does this process depend on?

‘There have been other researchers in the North Atlantic Ocean, but they don’t perform the tests the way we do’, says Stefels. ‘If all you want to do is make an inventory you can just sail around and take samples. But not everyone actually looks at the production mechanism, which is a much more laborious process’, Van Leeuwe adds.

It was a ridiculous place with these Disney World-like resorts, extremely touristy

The researchers boarded the vessel in the Bahamas on its journey to Ireland. Uncomfortably, they waited at the harbour. ‘It was a ridiculous place with these Disney World-like resorts, extremely touristy’, Stefels says. ‘Not a place you want to vacation’, Van Leeuwe chuckles.

It did, however, impress upon them the importance of their research. Stefels: ‘There were no animals, because the amount of algae was so low. But as soon as we made our way towards Newfoundland and the algae population grew, birds and dolphins also started to appear.’

Magical

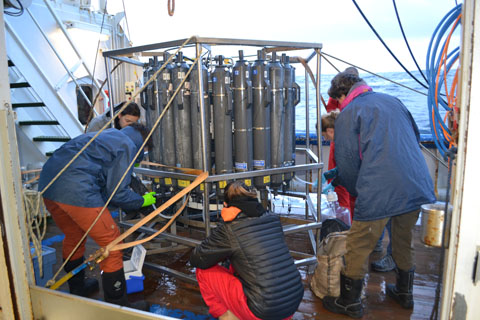

On the Pelagia, the day starts with bringing the tank of ocean water, a magic moment for Van Leeuwe. ‘We were on deck before sunrise. Everyone was so eager to get to work. The first container would get pulled up on board as the sun was slowly coming up. We could see dolphins swimming far away. When the weather was bad a wave would sometimes come crashing over the side, drenching everyone.’

The women laugh as they tell the story. ‘And then you would spend the rest of your day mucking about in your own containers. That wasn’t quite as exciting.’

Seasick and permanently slanting

Doing lab work on board is quite a bit more challenging than at the Linneausborg. ‘In the beginning we would get so seasick, because there was no horizon to focus on’, says Stefels. And everything in the lab had to be screwed down. The ship not only moves, but it’s also permanently slanting over to sluice out the water.

Van Leeuwe: ‘It’s kind of funny, but after a while I got sick of it.’ Fortunately, most researchers found their sea legs after a few day, and worst of the seasickness had passed. That is, until the next adventure. ‘On Friday the thirteenth, the day that the Titanic sank, we were sailing past the spot where it did’, Van Leeuwe says. ‘Luckily we survived.’

In the beginning we would get so seasick, because there was no horizon to focus on

Van Leeuwe and Stefels have since returned to their offices at the Linnaeusborg. After catching up on a lot of sleep, they now occasionally look back on the trip through videos and photos. They’ve done an enormous amount of work, more than they had anticipated. Now the question arises whether it will lead to anything. Their samples are still on the Pelagia, which will sail until 28 July, taking on new researchers along the way.

There is one thing the women are sure of: the Netherlands should definitely have a research vessel. ‘It’s ridiculous that some people are even questioning whether we should have our own ship’, says Van Leeuwe resolutely. ‘Dutch research is good, and there are numerous universities that do marine research. We should have the facilities for that. It also energises people, gets good results, and is great PR to engage the next generation of researchers’, she concludes.

Jacqueline Stefels and Maria van Leeuwe