Not good for anyone

Animal testing: regulated to death

How to get a permit for lab animals

Anyone who wants a permit to performs tests on animals has to go through three different authorities: the Animal Welfare Body (IvD), the Animal Experimentation Committee (DEC), and the Central Committee on Animal Testing (CCD).

Researchers write a first set-up for an application and fine-tune it together with the IvD. They mainly look at the technical aspects and whether there is sufficient emphasis on the three Rs (reduction, refinement, and replacement). Next, the application is sent to the CCD, who asks the DEC for advice. The DEC determines the scientific quality and evaluates the ethical aspects of the applications.

The CCD has forty days to process the application. This does not include the time needed to ask additional questions.

Once the permit has been granted, the IvD comes back into it. Together with the researcher, the IvD ensures that the experiments are conducted correctly.

Biologist Simon Verhulst thought the letter he got from the Central Animal Testing Committee (Centrale Commissie Dierproeven, or CCD) was a joke. Had they lost their minds over in The Hague?

Verhulst studies uses zebra finches for his research on ageing. He is trying to induce variations in life expectancy, for instance by making birds work for their food while they are brooding. This leads to some avian parents having to work extremely hard to raise a nest while others take it easy.

The expectation is that the hard-working parents will die sooner. The objective is to find out which mechanisms play a role in the ageing process.

But this can’t just be done willy-nilly. There are rules about the ways in which you can manipulate the lives of lab animals. To that end, Verhulst applied for a permit for the experiments.

The CCD, which checks whether the tests are truly necessary and whether the animal suffering can be diminished in some way, asked for more information. Their question was: ‘Couldn’t you use a species where you don’t expect to see an effect on their chance of survival?’

Verhulst is still angry about it. ‘This is the level of incompetence we’re dealing with. These people don’t know how to think like researchers.’

But he can’t do his job without a permit. And so, like a good boy, he complied,explaining in detail why it was a good thing to try and elicit a response. He then waited another month to hear back about his permit – which costs a thousand euros, by the way. Now he hopes that there won’t be any other questions, as that would mean more delays. It’s not unheard of for people to wait six months for a permit.

Frustrated

Verhulst is not the only one who’s frustrated. Ask most animal researchers about the CCD and they’ll tell you all about the bureaucracy, lack of expertise, high costs, and months of delays. And the absolute worst, says Verhulst: ‘They have no idea what it means for animal welfare.’

Of course, no one actually opposes the Experiments on Animals Act that was introduced in 2014. The researchers are not out to cause animals unnecessary discomfort and pain. They’re just trying to find the answer to important research questions. ‘But I don’t think we’re ready to try and do that without animal testing’, says cellular biologist Floris Foijer with ERIBA, a research institute which studies ageing.

So, they have to untangle a dense administrative jungle every time they want an application approved. It’s still a great source of irritation for Foijer, who had to send in a new application for his research when the new law was instated.

He conferred with the RUG’s Animal Welfare Body (Instantie voor Dierenwelzijn, or IvD), which is mainly concerned with implementation and the technical aspects of research. He also wrote back and forth with the DEC (Dierenexperimentencommissie, or Animal Experiment Committee), which considers the ethical aspects of animal testing, and then wrote an application for the next five years of his research. And then he heard nothing, for almost forty days.

‘A few days before the deadline, I received a phone call from one of the experts at the CCD. He asked me a few questions, said he noticed a mistake in the cohort calculations. So he’d clearly been paying attention’, he says. He explained the things that were unclear and figured that everything was fine.

Pissed off

‘But three or four weeks later they told me my application had been denied, because it wasn’t verifiable’, he says. That means it was difficult to ascertain whether the application complied with the rules. ‘I was pretty pissed off. And that’s putting it mildly.’

He was out a thousand euros, and he still couldn’t test on animals. He wanted to object the ruling, but was advised not to do that. ‘They said “You must be pragmatic. No one stands anything to gain from your objection”.’

But what surprised both him and the RUG’s legal experts: the CCD told him that his application would probably be approved, aka, be verifiable, if he split it up into two smaller applications.

‘But how did they know that?’ he wants to know. ‘It’s just because they want the applications to be as small as possible.’ Why? Because each applications nets the CCD a thousand euros, and the committee ‘has to pay its own way’. ‘That’s how you create an administrative monster.’

They’re splitting hairs

Foijer caved, wrote two new, practically identical, smaller applications, and was given his permit. But he’s still frustrated. He was out four thousand euros and he’d lost nearly a year’s worth of research. ‘They’re honestly just splitting hairs.’

It’s hard not to wonder: a committee that pays for itself with the money they earn from giving out permits? Isn’t that a conflict of interest? ‘I get nervous when there’s even the suggestion of a conflict of interest’, says Robbert Havekes, who studies the influence of sleep on how the brain processes things. ‘If a committee is this important, it has to be squeaky clean.’

Researchers say that it doesn’t have to be this way. Before 2014, the Netherlands had a perfectly fine system of local DECs that checked up on animal testing practices. Communication was swift and any lack of expertise quickly resolved.

But then Europe introduced a new guideline that requires a more centralised approach. Even that didn’t seem like a problem, at first. ‘I thought things would get better’, says Foijer. ‘The big issues would undergo centralised inspection, while the practical implementation would be watched over by a central Animal Welfare Body.’

But the Netherlands went much further than the European guidelines required. Global inspection of scientific importance has become a speck in the rear view mirror. Havekes calls the development ‘worrying’. ‘The applications have to be increasingly detailed, and we’re losing flexibility. But flexibility is crucial to science.’

At the same time, the exasperation just keeps growing.

The lack of scientific expertise is distressing

‘The lack of scientific expertise is distressing’, says Sietse de Boer. He studies aggression and uses rats for his research. He is also a former member of the local DEC. It is impossible to have people from every scientific discipline imaginable in the committee. ‘So we tailor our applications, writing them clearly and in the style of popular science, to prevent stupid questions’, he says.

It’s what the IvD calls a ‘quality application’. And this quality ‘strongly influences the turnaround time’ on applications.

That means researchers have to use proper language, and their applications have to be carefully structured and include detailed figures and tables. ‘We get applications that are just one big jargon-y mess’, says Miriam van der Meulen with the IvD of Science and Engineering. And that’s a problem. It doesn’t have to be kindergarten-level writing, ‘but it should be readable’.

Mistrust

But the lack of trust built into the process is hurtful. On top of that, the lack of flexibility is downright detrimental. In this day and age, says De Boer, there is no such thing as crappy research. Scientists who don’t know how to do their job might as well pack their bags. But the CCD doesn’t seem to realise this. ‘Everything just comes from a place of mistrust.’

What if you’ve done good research and you’re about to publish in one of the top journals, but that journal asks you for an additional experiment that your application didn’t cover? ‘We could never get it done in the time they’d allot’, says Havekes.

‘The new law was supposed to ensure a level playing field in Europe’, says De Boer. ‘But that’s not what happened.’ He and many others fear a brain drain, where scientists leave for better working conditions abroad. It’s no problem if they leave for somewhere else in Europe, but what if they leave for China? That country barely has any rules to minimise animal suffering.

The IvD advises the scientists to anticipate unforeseen circumstances. They should write wriggle room into their applications. Don’t write an application for five tests, but include a sixth, unforeseen test. Because if you don’t, you might run into trouble. ‘It is a learning process for every researcher’, says Van der Meulen.

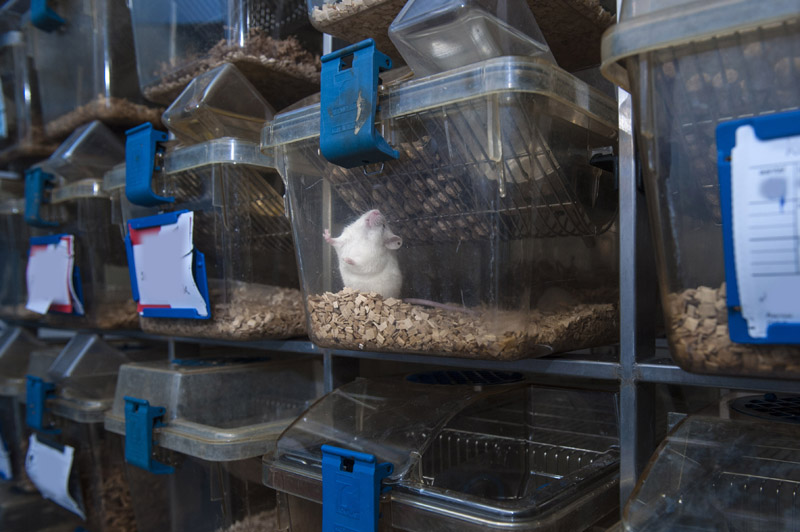

But while the researcher bury themselves in mountains of paperwork, the animals are no better off. The IvD acknowledges this. What’s more, it could even detrimental to the animals. While Foijer was waiting for his permit, unable to start his tests on genetically modified mice, sixty to eighty animals were ‘euthanised’ without ever being used. ‘After all, you can’t just put a stop to a line of genetically modified animals.’

Verhulst thinks it’s awful. While he wrestles with yet another CCD question so he can inject a natural hormone into jackdaws to learn more about ageing, fishermen let their catch suffocate on their boat decks and thousands of chickens are destroyed at once, all without anyone giving a crap. ‘The rules aren’t the problem’, he says. ‘But their implementation is.’

Response CCD

The CCD states that from 1 January, the application procedures for animal testing have changed. Since then, it takes forty work days for the CCD and DEC combined to process the applications. ‘This period is necessary for a thorough consideration that not only does justice to the research, but to ethical standards as well. In short: an analysis is made of the damage versus the benefits.’

‘Figuring out what a research application should look like and what kind of information it should contain in order to be able to properly assess this, is an ongoing process’, the committee states. ‘The CCD is well aware of this and we offer various guidelines on our website to help with this.’

As for the criticism concerning the lack of expertise and the unneccesary questions, the committee explains that the different roles the law prescribes took some time to fully take shape. ‘Certain issues were not yet fully clear when the system was first implemented, but they are now. The CCD strives to keep completing the forms, so additional questions will no longer be necesary in the future.’

Researchers needn’t fear a conflict of interest, says the committee. The CCD is an independent administrative body – and thus is not allowed to make a profit. ‘The CCD’s funding does not influence whether or not a permit is granted.’

Lastly, the CCD states the actions performed on an individual animal should always be made explicit. ‘This is the level of detail we demand.’