Guinea pigs #5Virtual stress test

‘I stutter my way through the assignment’

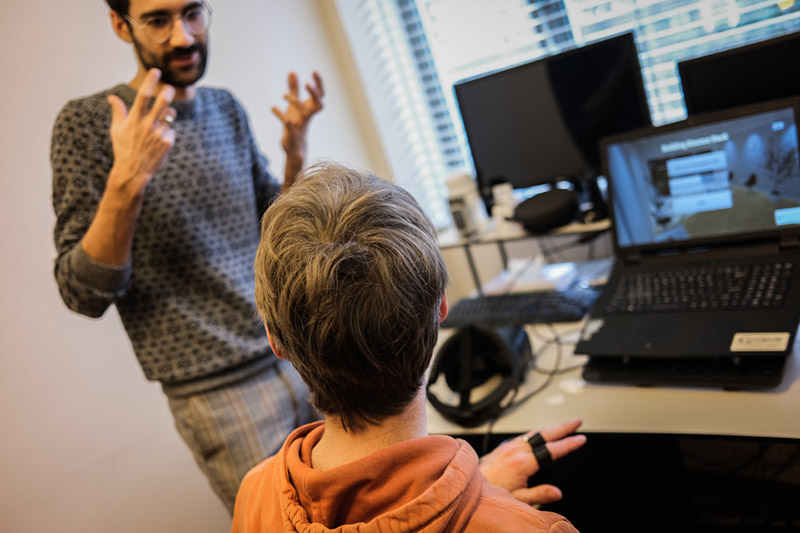

PhD student Mathijs Nijland’s virtual reality experiment feels kind of alienating. The whole time, I was wondering if I was in the right place.

The experiment takes place in three locations: one real location and two virtual ones. The real location is a small office for one at the UMCG’s psychiatry department, where Mathijs sits me down at a desk with a view of the Petrus Campersingel.

There are four screens in front of me, but I’m only using one, to fill out the questionnaires after each section. They ask me about whether I sweat, whether I can feel my heart beating, or if I’m tense at all. At the same time, a roll of cotton balls sucks up the saliva in my mouth. Mathijs also hands me five electrodes, which I dutifully stick to my chest and stomach, after which Mathijs attaches another two to my fingers.

Waiting room

The test starts. A large set of VR glasses is placed on my head, transporting me to the second location: a waiting room in what looks like a crematorium. Large windows reveal grass fields outside, and the room holds a few magazines as well a row of chairs and a coffee table. In front of me is a large television screen. When I look at it, a solemn voice-over starts talking about the new Marker Wadden archipelago and the nature there.

Next, a virtual man appears who just as solemnly tells me I have to wait for twenty minutes. He points to an analogue clock on the wall and a small clock that’s counting down on the table in front of me. I look around for a while, but the only thing I can do is watch the documentary on the television. I can’t pick up any of the magazines and I can’t see my phone.

I try to pay attention to the screen. The documentary is now talking about great crested grebes. Next, there’s a bluethroat on screen, and after that, I watch an insect emerge from its cocoon. The whole time, I’m wondering if I’m even in the right place. Did I accidentally meet with the wrong researchers? What are they even testing here? Whether I can see that the time is secretly moving faster than it’s supposed to? How often I look at the clock? What am I doing here?

New version

This experiment is known as the Trier Social Stress Test. As Mathijs explains, it’s usually performed live, with real people. What I’m doing is the new, completely virtual version, developed in conjunction with the UG’s Centre for Information Technology.

It’s more convenient because you no longer need actors, and it’s cheaper, too, says Mathijs. ‘All you need is a small room, a set of glasses, and two computers. Not much else. But more importantly: ‘The circumstances are always the same.’ That makes it easier to compare the results.

Twenty horribly slow minutes and various animal species later, I can finally remove the VR glasses. I get another questionnaire to fill out and some more cotton buds to drool on. The screen asks if I’m nervous. No, I think, I’m bored, but that’s not an option on the questionnaire. I’m surprised the photographer hasn’t left yet. ‘This is where it gets interesting’, she grins.

Presentation

I’m ushered into a different virtual room where I’m given five minutes to come up with an equally long presentation, to be held in front of two people and a camera, about my dream job.

I rack my brain trying to think of my dream job. I’m actually really happy doing what I do now. I manage to come up with something just before my time runs out. I stutter my way through the assignment while a man occasionally drums his fingers on the table and a woman studies her nails, clearly bored.

Later, Mathijs will tell me that this was the neutral version of this video. ‘There’s also one that’s particularly nasty. The people look at you angrily and tell you mean stuff, like you’re talking nonsense.’ But there’s also a positive version that serves as a control. There are no bored people and no camera, the conversation is about your holiday, and the only assignment is a simple sum.

Cortisol

Unfortunately, I don’t get the easy version. I have to count down from 1,022 to 0 in increments of 13. I’m pretty sure my stress levels hit the roof the moment I heard that I had to do maths. I come up with the first number after what feels like a minute. I’m transported back to my primary school days when I was the last kid to finish their multiplication tables, and I feel like a huge loser.

Not only will the next questionnaire show that my stress levels have risen sharply, but so will the cortisol in my saliva (collected by the cotton buds) and the readings of my heart rate and the sweat on my fingers. When I’ve finished the questionnaire, I get to go back to the waiting room. Halfway through my stay, the documentary starts up again.

The glasses feel heavy on my face and my eyelids are starting to droop as the voice-over keeps going on about dragonflies, spoon bills, and gulls. The footage is lovely, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not exactly as riveting as, say, a Marvel movie. But as Mathijs says, it’s deliberate: excitement will mess up the readings.

Resilience

Dealing with stress starts with the realisation that you are, in fact, stressed, Mathijs says. ‘That’s when you realise that you are, for instance, squeezing your hands tightly. Stopping that kind of behaviour lowers your stress levels.’ But breathing exercises can help, too, he says. Just deeply breathe in and out a few times.

Research group Bounce Back, led by Catheleine van Driel, studies stress and how to improve people’s resilience to it. The idea is that this VR test can help. ‘Exposing people to a stressful environment can teach them how to cope with stress, but it also gives us insight into how their stress response works’, Mathijs explains.

Finally, I have to wait another twenty minutes. It takes approximately forty minutes for people to come down from their highest level of stress, Mathijs explains. But my cortisol levels are so high that I just want to go to bed.

- Faculty: Medical Sciences

- Duration: 90 minutes

- Remuneration: None