Guinea pigs #2Driving while distracted

‘Phew, I finally made it’

The phrase ‘one look can be worth a thousand words’ suits the driving experiment conducted by Mart Berends. For the master student in human-machine interaction, the eyes of a car driver are the main indicators of cognitive overload. In simpler terms: they tell him when a driver is feeling overwhelmed by external stimuli.

Using eye-tracking, he is trying to come up with a semi-autonomous system that can judge when a driver might need a bit of help and intervene on its own, something that’s called adaptive automation. Today, I will be that driver.

Mart guides me into a small room. It is nearly empty, except for two desks, some desk chairs and two computers. On one of the desks sits a steering wheel and on the floor I notice pedals. On the computer monitor I see a cartoonish image of a straight highway road. ‘This will be your car’, he says.

Working memory

The idea of the experiment is that participants have to perform a task that asks a lot of the working memory, while they drive. ‘We hope to use the eye-tracking data to see whether they are having a hard time combining the two tasks.’

He starts setting things up. I take a seat in my ‘vehicle’ and try the controls: brakes, gas, steering. As I floor the accelerator pedal, I notice a square in front of me, moving in the same direction. ‘That’s supposed to be another vehicle, controlled by AI’, Mart explains.

‘Can I race it?’ I ask excitedly. ‘You can try, but please don’t crash into it, as that will crash the whole simulation and I will have to set up everything again.’ I start feeling a bit of pressure: the process of setting up took about 15 minutes.

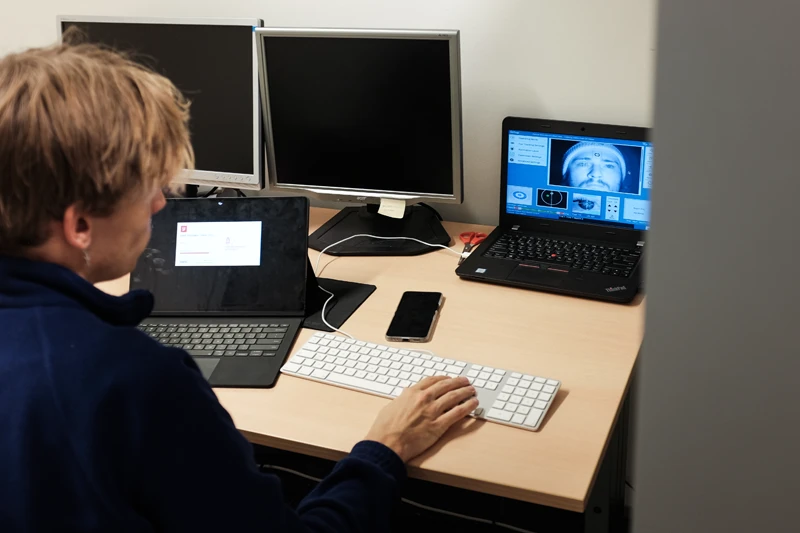

Mart now sets up the eye tracking camera, fitted right in front of me. And he instructs me on how to sit in such a way that the camera can easily track my eyes. We do a couple of calibration tests. All of this takes another ten minutes. But then, finally, I am ready to go.

Four levels

As I start accelerating, speed signs appear on the right side of the road. My task is to remember what the speed limit is, and drive accordingly. Sounds simple enough. However, the tricky part is that there are four different levels in this exercise. In the easiest one, I just have to remember the speed limit of the previous speed sign. But in level four, I have to drive according to the speed that was displayed three speed signs prior to the last one.

The test begins in the hardest level, level four, and I realise pretty quickly that this is not going to be the relaxing drive that I thought it would be. My brain is already starting to feel overwhelmed.

‘In previous studies, we studied brain data to try and predict situations of cognitive overload’, explained project supervisor Moritz Held beforehand. ‘This time, we are trying to do the same thing, but rather using physiological data, such as pupil size, which is much easier to collect as well.’

Pupil size

For that, Mart looks at how fast my pupil size changes. ‘When your pupils dilate, it means that you’re cognitively overloaded. Based on this, we can then decide to automate the system partially, by taking over the steering wheel for example; or fully, by taking over the wheel as well as the pedals.’

So what kinds of real-life situations might such a system be useful for, I ask? ‘When a parent is doing a morning school run with three energetic kids in the car, for example, while also being on the phone, there is a good chance the parent will be cognitively overloaded’, Mart says. ‘This is when the autonomous system of the car will be able to make the decision to take control, in order to avoid unpleasant situations in traffic.’

After driving for ninety minutes straight, I feel the same kind of tiredness I get after driving a real car. When I finish, all that is going through my head is: phew, I finally made it.

More precise systems

Mart shows me the results of my driving skills on a complicated chart that I don’t understand. He smiles. It’s not me, he doesn’t understand it either, yet. ‘I have to first compare them with the ones of the rest of the participants.’

Mart and Moritz hope that their research project will contribute to the development of better and more precise autonomous driving systems. They believe that in the future they will be able to predict overload situations without the aid of an eye tracking system, but rather with the help of a model that they are currently developing.

Before I leave, Mart reminds me to fill out the participation form, so I can be paid for my time. I had forgotten about that. Not only have I helped science, but I also earned myself a nice dinner for today. Not bad!

- Faculty: Science and Engineering

- Duration: 90 min +15/20 min preparation

- Remuneration: 15 euros