Ralf Cox reveals how we feel about art

Measuring the intangible

Two large tree trunks fill the space. They shimmer in light that is designed to mimic that of the moon, while people carefully walk around them.

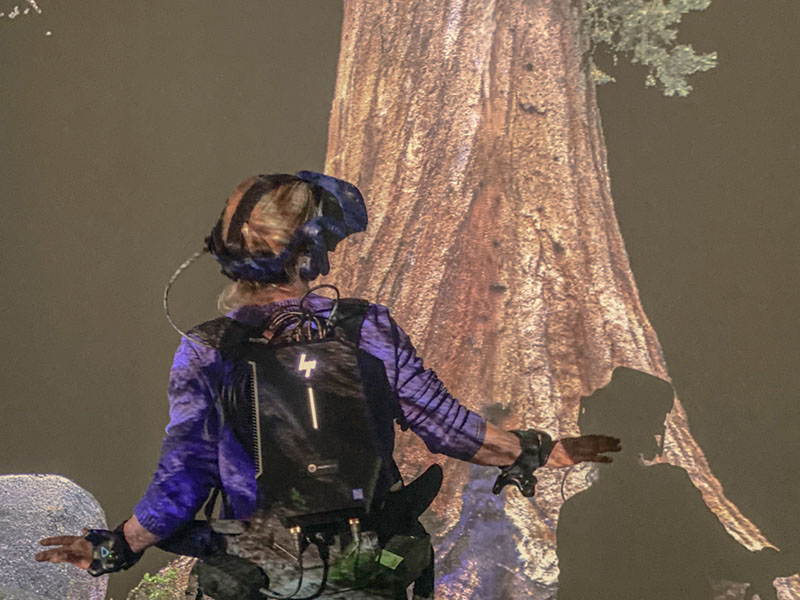

The next room is empty, but as soon as the virtual reality equipment is turned on, it’s flooded with life. Visitors are instantly transported into the most intimate parts of virtual trees, observing how water flows inside them.

People feel things when they see these works, part of the Frankfurt Art Association’s exhibition The Intelligence of Plants which focuses on the relation between humans and plants. They may be startled, moved or challenged. They may experience anger, sadness, a sense of poignancy.

But how exactly do they feel that? How do their bodies respond?

Smartwatches

That’s something associate professor of developmental psychology Ralf Cox, arts professor Barend van Heusden, and a group of PhD and master students really want to know. They gave visitors of the exhibition smartwatches that registered their heart rate and recorded motion-based activity and the electrical properties and temperature of the skin.

Others were asked to fill out questionnaires about their feelings and physical sensations watching the works of art. ‘We want to know what it means to “experience” something’, Cox says.

Cox has been interested in how people connect with their environment for a long time. Looking at art is one way of doing that, he says. When someone enjoys a painting or installation, they focus on a specific part of it, and that affects their thoughts, behaviour, and emotions.

Art is a tool that allows us to feel certain emotions

‘Some people argue that art is a tool that allows us to feel certain emotions. It allows us to understand the world in a way we couldn’t if we didn’t have art’, Cox says. He likens it to a hammer used to drive nails into walls. ‘Without it, we can’t get the job done.’

The idea suddenly came to him. Why not measure the whole experience of art? Not just the change in heart rate that some researchers have found, or the change in movement that others detected, but everything?

‘That’s not something you can do with just one measurement, though’, Cox says. ‘A lot of previous research has been done by surveying people using a scale from one to a hundred. That’s important too, but if you want to know more about engagement, you need more.’

Interactive

The Frankfurt Art Association seemed like the best partner to start diving deeper into this, because it often combines its art exhibitions with topics like science or technology. After consulting with curator Franziska Nori, Cox decided to focus on two specific installations: the double sculpture Embalmed Twins I and II, inspired by two centuries-old oaks, and the virtual reality installation Treehugger: Wawona.

The goal is to capture people’s individual experiences with art

‘The museum’s goal is to create exhibitions in which two fields come together. In this case, it merged art with biology and allowed people to actually engage with the works. People could walk around the logs, change their distance towards them or actually touch them. The VR installation was also very interactive and engaging’, Cox says.

Visitors were happy to participate in the study, it turned out. ‘Some people who had already seen the installations came back for a second visit so they could be part of it.’

And even though not everything went according to plan – like when the watches didn’t register the data well, or when visitors had to return to the museum to finish their test – the researchers are happy with the readings they’ve gathered so far.

Upper bodies

The VR installation, for example, mostly evoked feelings in people’s upper bodies, says PhD student Gemma Schino, while the static sculptures engaged all of their bodies. The VR induced more positive and active emotions such as interest, joy, and pleasure, while the sculptures brought about more gloomy feelings, like sadness and disgust.

Héctor Gallegos González, another of the PhD students working on the study, advises caution when interpreting the results, though. After all, the emotions the participants felt could have been influenced by the installation’s content, rather than by the type of installation.

You could both fill out a body map for a specific work of art

It’s too early to draw any real conclusions, Cox says. To understand what all of this means, they have to link the data to other measurements they’ve gathered. And they’ll need to do more experiments. ‘What we did at the Frankfurter Kunstverein was just a pilot. But it can lead up to more studies, more measurements and more museums participating. The goal is to create a framework and database that captures people’s individual experiences with art.’

Conversation starter

Museums could use such data to find out whether they are evoking the kinds of feelings they are aiming for. If – for example – an exhibition that is framed in a sombre and sad way makes people happy, then something is not right.

But there are other possible uses as well. Having your feelings mapped out might make it easier to talk about what you feel and where you felt it, for example.

That way, suggests research master student Lisa-Maria van Klaveren, art lovers could compare their experiences with those of a friend. ‘You could both fill out a body map for a specific work of art and use that as an invitation to talk about the artwork. Then you can go beyond just saying: “I like this artwork” or “This is beautiful”. It makes it less abstract.’