Trans women excluded in public spaces

You don’t belong

The world is not built for people like them.

That is the message Jody Holland constantly gets. When going to toilets that are hardly ever gender neutral; when entering a clothes shop that has a department for men and a department for women, but nothing in between; when walking the streets where people attack her just for the way she looks.

The world she and other trans women live in is built for heterosexuals and cisgender people – those whose gender identity corresponds to the gender that was assigned to them at birth. ‘It’s exhausting to be constantly reminded of the fact that you don’t belong’, says the 24-year-old student of spatial sciences (she/they).

It happens almost everywhere. Even in cities like Groningen that celebrate inclusivity on the one hand, but perpetuate the problems on the other. ‘The amount of complaining I’ve done about going to shops with only male and female sections and getting weird looks when going to the female section.’

However, very little research was done on the needs of transgender people from a spatial perspective. And so, together with one other transgender student, Sam Ďurkáč (she/they/he), and cisgender Dana Pokojná (she/her) and Angelo Galindo (he/him), she decided to dive into spatial transmisogyny in their research master at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences. The students looked at the way trans women are being excluded from certain places in the Groningen city centre.

Zines

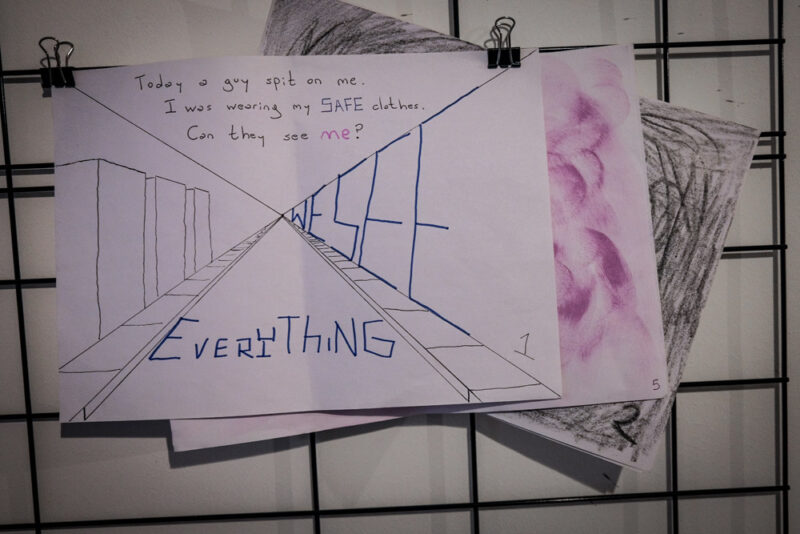

The students decided to use a completely new way of gathering data. They allowed participants to communicate through zines, an underground art form used for sharing information in marginalised communities. Combining drawing, collage-making, and written texts, participants had freedom and control over explaining their experience.

People are screaming for their voices to be heard

‘Today a guy spit on me. I was wearing my SAFE clothes. Can they see me?’ says one of the artworks. It shows closing walls with the words ‘WE SEE EVERYTHING’ on them that evoke spatial anxiety. Another zine is full of dark smudges with ‘I will never be safe’ written in the middle of the paper.

‘These zines clearly show that people are screaming for their voices to be heard’, Jody says. ‘It doesn’t sanitise them, it’s raw.’

And that is a good thing, she feels. Traditional methods of academic inquiry often strip away the emotional element of people’s stories, Jody says, but you cannot detach emotions when someone talks about their trauma.

Rainbow capitalism

The students cross-analysed the zines and identified recurring themes based on which they articulated some of the key features of spatial transmisogyny.

An important one is so-called ‘rainbow capitalism’: corporations and governments presenting themselves as LGBTQ+ inclusive by, for example, flying rainbow flags, without any effort to create inclusive spaces. ‘A classic example would be a shop selling pride flags, but still being rigidly segregated, with male and female sections’, explains Jody.

It shouldn’t be terrifying just to shop for clothes

Jody’s subjects wouldn’t enter store stores like that, she says. They either prefer to shop online or go shopping with an assigned-female-at-birth friend for women’s clothes. ‘It shouldn’t be terrifying just to shop for clothes.’

Spatial deprivation is another key problem, the students found. This means trans women are excluded from particular places either because of rigid gender binary segregation or because they didn’t feel safe there. ‘Every trans woman I know has been heckled, made fun of, or harassed on the streets’, says Jody.

The city centre of Groningen has plenty of outdoor drinking spaces which may be intimidating for trans women. ‘If I’m wearing a dress and lots of makeup and I’m alone, I avoid those spaces, but it’s almost subconscious at this point.’

Gay village

One solution would be to provide a safe space for the queer community in the form of a small gay village. Jody thinks what’s missing in Groningen is ‘community empowerment, participatory planning, and grassroots urban design.’ This would mean direct inclusion of the queer community in the discussion of city planning.

You need to pee and you wonder: Do I look feminine enough today?

The lack of gender-neutral toilets in Groningen is a serious issue. ‘You need to pee and you’re staring at a men’s toilet and a women’s toilet and you’re doing this calculation in your head: Do I look feminine enough today? What if I don’t?’

Jody has mapped which toilets in Groningen feel safer than the others. The ones at the Forum are too exposed, but the ones above Jumbo at Grote Markt are a bit more tucked away. There aren’t any gender-neutral toilets at her faculty, and she only has fifteen minutes during the break to walk to another building.

‘And don’t even get me started on gyms or swimming pools. The idea of using a changing room – I don’t think I could do it’, says Jody. She used to swim a lot before she came out as trans, but she doesn’t know about any swimming events for trans people in the Netherlands. ‘It’s a shame, because I used to love swimming. And that is painful.’

Identification

Participants in the study also expressed negative connotations with over-policing and surveillance. Being required to present an ID can be traumatic for trans people whose deadnames are on it. ‘If I were forced to show my ID, even at borders, I’d be humiliated’, says Jody.

When trans people are asked by the police to show their identification, they are essentially forced to come out as transgender. ‘They have the power to deny us our identities. They have the power to strip away every effort we make in the morning to present ourselves.’

Jody says Western European politics are often seen as progressive, yet trans people still have to fight for their rights every day. ‘You have to constantly be an activist when you’re a marginalised person because rights can be taken away’, she warns. ‘If there is injustice in the city centre, let’s not pretend there isn’t.’

However, she hopes to be an agent of change. Many trans people, like Jody, decide to leave their home countries for better alternatives. ‘It’s the sense of: where do I go? Where is it safe for me in this world? And that makes you passionate to work on making this city a better place.’

Getting her degree, doing this research, can be a step in the right direction. ‘It’s empowering learning how to research something and elevate disenfranchised voices.’