Four months at the North Pole

‘You can’t just end climate change’

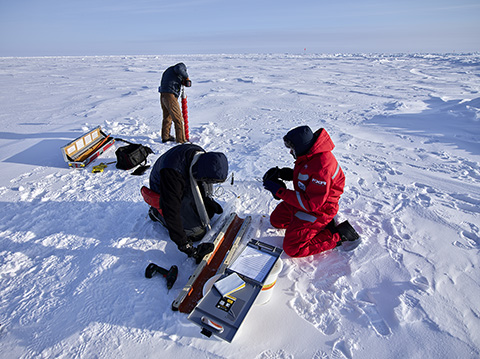

Patric Simoes Pereira (front-left), Jacqueline Stefels (front-right) preparing analyse of ice core from Jeff Bowman (back-left) Photo by Alfred-Wegener-Institut / Michael Gutsche (CC-BY 4.0)

Temperatures often reached minus forty degrees Celsius. Days go from twenty-four hours of darkness to twenty-four hours of sunlight. Participants in the largest North Pole expedition ever will always have a story to tell once we get back to having parties.

Sometimes, marine biologist Jacqueline Stefels (61) would be standing on the brige of the research ship, on the lookout for bears. She’d even been taught how to shoot, just in case she ever ran into a bear. On top of all that, she’s also working to save the climate.

Stefels says it was an adventure. The expedition has renewed her energy. She stays humble, though. The real work hasn’t started yet. ‘I collected masses of data. That is only the beginning.’

Climate models

The North Pole is warming up faster than the rest of the world. Based on their current knowledge, scientists predict that if CO2 emissions continue as they are, temperatures will have risen by five to fifteen degrees in the year 2100. Temperatures at the South Pole are expected to increase by one to six degrees. But climate predictions aren’t an exact science. Climate models are often lacking data from the North Pole. The MOSAiC research expedition – Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate – hopes to change this.

We realised no one would be coming to get us

In October of 2019, German research ship Polarstern purposely froze itself in the polar ice. Over the past year, approximately 250 scientists from twenty countries arrived on the ship to collect climate date.

The organisation would have been remiss to not invite Stefels. She hums in agreement: ‘That pretty much sums it up.’ The biologist has been studying greenhouse gases her whole career, and she’s an expert on ice. She founded the BEPSII network (Biogeochemical Exchange Processes at the Sea-Ice Interfaces) which grew into the pre-eminent international partnership for chemists, biologists, and modellers who study sea ice processes.

Scientist carrying equipment in front of RV Polarstern. Photo by Janek Uin (CC-BY 4.0)

She focuses on the relationship between the greenhouse gas CO2 and the substance dimethyl sulphide (DMS), which is produced by sea algae and is responsible for half of the emission of natural sulphur into the atmosphere. It’s the main substance in cloud formation. Since clouds protect the earth from the sun and help it cool down, Stefels also calls DMS the ‘anti-greenhouse gas’.

Corona

Stefels was supposed to board the ship halfway through February in order to study the seasonal change from winter to spring. But the Russian icebreaker transporting her and the other scientists in her group couldn’t get through the thick ice, and the journey was delayed by two weeks.

The ice floe we were stuck on started to crack

‘Before we even arrived, we were told to prepare for the next group to replace us. We were all like, hell no’, she recalls. ‘A week later, the world went into lockdown because of corona. We realised no one would be coming to get us. That was an entirely different problem.’

Halfway through June, two months later than she was supposed to, the biologist returned to Groningen, where social distancing had become the norm. She considers her extended business trip an opportunity. ‘I worked so much and so hard.’

She took water and ice samples at the North Pole and performed a rudimentary analysis on them in her mobile laboratory. ‘We tried to analyse air samples as well. But it was so cold that we couldn’t detect any DMS.’

Polarbear mom and cub get close Polarstern. Photo by Alfred-Wegener-Institut / Esther Horvath (CC-BY 4.0)

Fifteen cases

Groningen scientists at the North Pole

After four months on board the Polarstern, Jacqueline Stefels was relieved by her post-doctoral student Deborah Bozzato, who in turn was succeeded by Alison Webb, one of Stefels’ earlier post-docs who set up a project in England. Stefels still works with her.

UG biologist Maria van Leeuwe (55), Stefels’ life partner, was supposed to close out the expedition. But when corona arrived, she decided to let the young post-docs take her place. Van Leeuwe, who had previously joined Stefels for research in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, said her time for ‘adventure’ was over.

After taking a corona test, she once again boarded the Polarstern last week. The ship had returned to its home port of Bremerhaven on October 12. Stefels returned to the ship to dismantle the lab container research organisation NWO had provided for her. Fifteen cases full of barrels and bottles, a mass spectrometer and other equipment from Groningen will soon be shipped back to the Netherlands. ‘I’ll probably have to rent a truck to get them from the island of Texel. They’ll deliver the container to maritime research institute NIOZ there.’

She and her post-doctoral student Deborah Bozzato will be poring over all the data. She wants to find out how an increased level of CO2 in the atmosphere impacts the production of DMS. How will the algae react if global warming leads to the disappearance of sea ice on the North Pole? ‘If the sea ice disappears, I expect there to come a turning point where algae will start disappearing and the production of DMS starts dropping off. But it’s unclear when that turning point will come.’

She has seen remarkable things with her own two eyes. Ominous things. ‘We’d only been on board the ship for one or two weeks when the ice floe we were stuck on started to move, crack, and buckle. We hadn’t been expecting it; the group before us only saw small cracks here and there.’ It reminded her of the places she went ice-skating in Noord-Holland, where she was born. ‘The ice was ridged and white, with a vein of dark ice running through it, since the ice would re-freeze immediately.’

You can’t just stop the temperatures rising

When it was finally time to welcome the next group and go back home, the airplanes meant to take them home were unable to land. The landing strip next to the ship had broken into pieces. ‘We took the Polarstern and left the ice, travelling towards Svalbard, five hundred kilometres away. We and our successors swapped ships there. We took their ships to go to Bremerhaven, and they took the Polarstern back to the ice floe.’

Two degrees

Stefels had never been to the North Pole before, and the scientist in her prevents her from drawing any conclusions from the ice cracking. But she’s also a climate pessimist, and it’s made her feel uneasy enough to know that the situation is serious. ‘In 2015, the world agreed in Paris that we need to keep the temperature increase on earth under two degrees. But we’re poised to far exceed that, even if we put an end to all CO2 emissions right now. It’s like a speeding train: you can’t just stop it. It will take centuries.’