Academy building gets a facelift

What’s behind the scaffolding sheets?

Arjen Dijkstra is so happy. The Academy building is being painted, allowing the historian and head of the University Museum to get a closer look at the decorations on its façade. It’s a once-in-several-decades, if not a lifetime, chance. He’s a little apprehensive, though: ‘You know the previous Academy building burned down while it was being painted, right?’

But the work is necessary. The sandstone statues adorning the building’s façade have been eroded by rain and wind. The gilded ornaments have lost their colour and the paint work is peeling. The brickwork is at risk of tearing, and obelisks are in danger of detaching. It’s time for a facelift.

The Academy building is over one hundred years old. People might think the impressive building dates back to 1614, when the university was founded, but it is in fact the third academy building in Groningen. The first building was a one-storey, simple building, part of the beguinage at the Broerstraat. The arches above the entrance are a remnant of the gate to the cloister of before.

The second building was constructed when the original fell into disrepair and was beyond saving, in 1850. It was a severe, neoclassical building, and the academics at the time did not like it. ‘It was too small, too dark, and was always in need of repairs’, says Dijkstra. It was a shame, since it had been built with money raised by the citizens of Groningen.

Rush job

Then the fire destroyed that building in 1906 and a new one had to be built fast. The current Academy building was a rush job: ‘The fire happened on August 6’, says Dijkstra. ‘They’d completed the blueprints for a new building by August 9.’ Perhaps, he muses, this is why the building looks so much like the Gymnasium Haganum in The Hague, which was also designed by Jan Vryman.

‘Wasn’t that a conscious decision?’ construction manager René Bosscher, who oversees the RUG’s historical buildings, asks. ‘I read that this was the original 1614 design.’

Dijkstra shakes his head. ‘That’s a myth. A really old one, too.’ People immediately complained when the third building was finished. ‘They said the renaissance revival style with its baroque accents and classical adornments was old-fashioned’, says Dijkstra. ‘The curators tried to justify their choices by lying that it was the original design.’

Today, the 28-metre high building has been hidden behind orange sheeting for weeks. Plastic sheets cover the stone steps. It’s time to discover the secrets of the building’s façade.

Nec Pluribus Impar

We climb the third set of scaffolding and, at eight metres in the air, find ourselves on the Academy building’s balcony. Above the doors is a phrase, in Latin: Nec Pluribus Impar. The letters have been redone in shining gold leaf.

Dijkstra thinks for a while before coming up with the translation. ‘Not unequal to others.’

The phrase fits with the university’s attitude in the past, he feels. They were trying to say they were better than ordinary folk. ‘Something like ‘everyone in the academy is equal, but they’re also better than everyone else.’

Fun fact: the motto had previously been adopted by the French Sun King Louis XIV, under whom the Netherlands suffered quite a bit in the seventeenth century. Louis XIV was criticised for his motto; while his followers translated it as meaning ‘alone against all’, many of his contemporaries interpreted it to mean ‘above all’ or ‘I am the most powerful’.

Sandstone faces

One level up, we pass the sandstone faces above the building’s windows. ‘Every single face is different’, says Bosscher, caressing the sandstone. ‘Just look at those details!’

No one knows who the faces are supposed to be. ‘The muses maybe?’ Dijkstra wonders. But there are only nine muses in total, and there’s a face over each window in the Academy building, as well as a whole set of them along the edge of the roof. That’s way too many.

Another hypothesis: ‘They would sometimes depict famous people from Dutch history’, says Dijkstra. Who could these people be, then? He has no idea.

Most of the faces are really well preserved, but one of them has some straight lines on either side of its nose. The nose was probably damaged, thinks Bosscher, and a new one was made to replace it. No one can see the difference from below.

Black patina

Up high, it’s a precarious mix of steps and gangways. We round the corner to the building’s left wing. Bosscher can’t help himself and has to touch the detailed garland cut out of the stone. Interestingly enough, many of them are black.

Bosscher nods but says this is not something that needs cleaning. ‘The sandstone is so soft that cleaning it would erase the details’, he explains. Besides, it wouldn’t stop the black sheen from returning. That’s because it’s not dirt, but rather a patina effect that takes place when the stone is exposed to the air.

Most importantly, though, ‘it’s okay for people to see that this is an older building. If you clean every nook and cranny, you get rid of that. It becomes like a Disney palace. That’d be a shame.’

Gilt pinnacles

We go up another level, passing the statues of Historia and Scientia, on the right and left side of the attic window, respectively.

Then, we get to the sandstone parapet with the two-metre high obelisks on the corners. Bosscher grabs one of them and tries to shake it. ‘See this? We were worried they might have come loose after all those years. They’re attached to the building with just a single metal pin. But they’re still firmly on there!’

The gilt ornaments on top shine as though they were made yesterday. ‘It’s double gold leaf’, Bosscher explains. Double gold leaf is a little thicker than regular gold leaf, which is usually only one eight thousandth of a millimetre thick, and therefore suitable for outside use.

The gold leaf is carefully cut to size and applied to the ornament using a brush made from the hair of a squirrel’s tale, says Bosscher. ‘Apparently those work best.’

The university’s coat of arms

Below us, the people on the Broerplein are beginning to look like ants. Students swarm into the library, and there’s almost no room for bikes to be found.

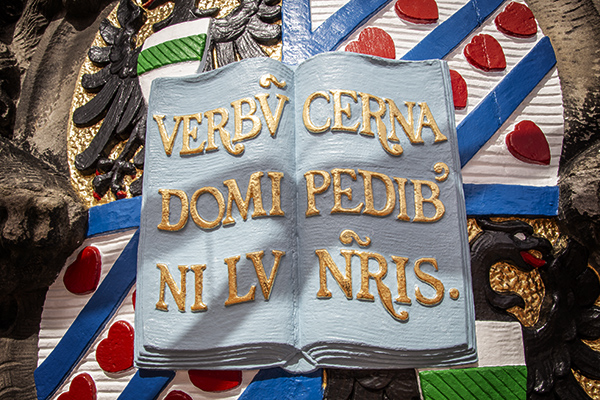

We have ascended above the building’s attic, where we find the university’s coat of arms. Two large lions are holding a shield emblazoned with the words ‘VER/BUM/DNILU/CER/NA’, the mediaeval abbreviation for ‘VERBUM DOMINI LUCERNA PEDIBUS NOSTRIS’: The word of the Lord is a light for our feet. Bosscher points out how vibrant the colours on the coat of arms are. ‘Once the scaffolding has been removed it’ll look brilliant’, he says, happy.

And, for the first time in twenty years, the coat will be displayed in the right colours. The previous workmen had painted the green areas, which represent the Ommelanden surrounding Groningen, blue. ‘Honestly I think blue paint is all they had left.’

No one noticed, until Bosscher climbed the scaffolding to take stock of the work that needed to be done.

Minerva

Finally, we reach the main attraction. Just below the building’s eaves is Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and patron of science. In one hand, she holds a shield depicting Medusa, the mythological figure with snakes for hair. But Dijkstra’s attention is drawn to her other hand. ‘Wait, what? What is she holding?’

Bosscher chuckles. ‘That would be a broomstick.’

He only recently made the discovery himself when he was inspecting the façade before the renovation. The beautifully detailed copper spear that Minerva once held in her right hand had disappeared and been replaced by a half-rotted broomstick. ‘Someone had attached a flat piece of metal as the spearhead and spray painted it gold.’

He found out it had been an emergency solution. ‘During the previous renovation activities the restorers discovered a hole in Minerva’s had. They wondered what she was supposed to be holding. The spear, obviously.’

Unfortunately, the spear had gone missing years earlier, and there was no time to have a new one made before the scaffolding came down. ‘The concierges decided to fix it with a broomstick.’

Now, history is in danger of repeating itself. The painting is nearly done, and the scaffolding is scheduled to be removed soon. Bosscher wants a forge to make a spear that resembles the original as much as possible, but he can’t do it before then. On top of that, there are no good photos of the original spear. ‘The only thing we know is that it was very meticulously made.’ The smith will have to do a lot of research. But one thing is certain, Bosscher says. Minerva will not be given another broomstick. ‘She will be holding something, and it will be metal.’

Dutch Lion

We finally reach the highest part of the scaffolding, at 28 metres high. Dijkstra bounds ahead to take a unique selfie with the Dutch Lion at the top of the building. ‘I’ll never have this opportunity again.’

The Lion has been alone up here for the past 110 years, and he’s looking remarkably good for his age. The shield under his paw shines in bright blue and gold. In his fist he holds seven arrows, a reference to the Seven Provinces. He is surrounded by eight golden cubes referring to the members of the House of Nassau.

Mathematica

From here, the only way is down. Dijkstra is looking forward to meeting Mathematica, the statue located on the right wing of the building. ‘I’m a maths historian after all’, he says.

He grins as we approach the statue of a tall woman with a bare midriff holding a golden globe. ‘See?’ he says, ‘that’s how you make maths sexy!’

But then he frowns. ‘Where is the compass? She’s supposed to be holding a compass!’

Bosscher takes a closer look. ‘Really? I was wondering why there are holes in the globe.’ He shakes his head. Turns out Minerva’s spear isn’t the only object that disappeared during the last renovation.

The compass will have to be replicated as well, he decides. Fortunately, he has proper photographs of Mathematica. A smith will be able to create a faithful copy. ‘Also, the compass is much less detailed than the spear.’

But where might it have gone? Bosscher doesn’t know. ‘Someone probably removed it to have it gilded, and it was left downstairs and disappeared.’

Prudentia

Dijkstra has to get back to the museum. He is already late for an appointment. Bosscher keeps going, walking all the way to the other side of the building, to Prudentia. A snake, the symbol for, you guessed it, prudence, is entwined around her arm. With her left hand she’s holding a shiny, gilt mirror, a reference to truth and insight into the self.

It’s all very beautiful. It’s also very expensive. The mirror alone is adorned with two hundred euros worth of gold leaf, Bosscher says. ‘We might ask ourselves if that’s necessary. Should we really be spending public funds on gilding these ornaments? And I say, yes, we should.’

The whole thing is given a lot of consideration, he emphasises. A lot people probably don’t realise that gold leaf lasts much longer than regular paint; easily fifteen years. But it’s also important to note that this is a classic historical building. The Academy building is the RUG’s calling card. ‘And the look of the building indirectly helps improve research and education.’

We find our way back down over the narrow gangways, towards the wooden door that keeps the general public away from the scaffolding. In just a few weeks, this will all be gone. Bosscher is looking forward to it: ‘Just wait, the building will pop when the sun hits the gold.’