Groningen’s collaborators in court

War criminals and their judges

Between 1946 and 1952, the Groningen Chamber tried 472 Groningen inhabitants. The trials were long and painful, but the general population loved them. Whenever the court issued a death sentence, the people in the audience would often even yell ‘Bravo!’

For the University of Leiden, Mieke Meiboom studied the Groningen Chambers’ special criminal jurisdiction after the Second World War. She received her doctoral degree for her research and turned it into a book called Foute Groningers?

The special jurisdiction started as early as 1941, when the exiled Dutch government realised they needed post-war criminal legislation. In radio broadcast, the government announced that everyone who has collaborated with the German occupying forces or committed international war crimes would be prosecuted.

Education minister Gerrit Bolkestein called upon the populace to write down the names of criminals and their crimes, and to start keeping journals. This directly led to Anne Frank starting her famous diary. In fear of people being publicly trialled, Justice minister Gerrit Jan Van Heuven Goedhart hastily added it was meant to ‘try people, not to murder them’.

The book mainly shows how many different kinds of war criminals existed. Meiboom: ‘On the one hand, there are the stupid people who just want to save their own skin or who are looking for an adventure, but on the other, there were also hardened war criminals. Finding out what motivated them, what they did, what one person can do to another… that’s something else.’

Meiboom shows the reader several different cases. There was the infamous Scholtenhuis, Groningen traitors, as well as those on the right side of history; Groningen citizens involved in the trails against the collaborators. RUG people can be found on both sides.

‘Hostage to the Germans’

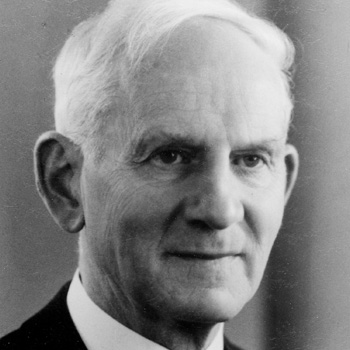

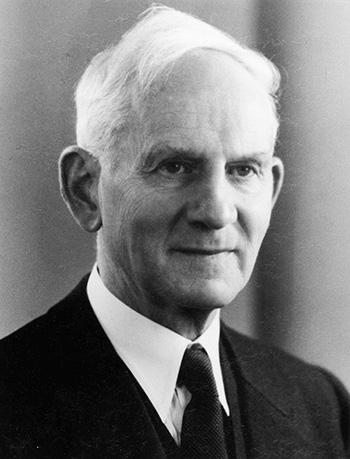

Willem Wolter Feith (1889-1973), Esquire

Feith was an important figure in the post-war trials. Before the war started, he studied law, becoming the city’s first juvenile court judge. He was beloved by many, in part because he held an open office hour on Saturday, which judges never did.

In 1942, he was arrested by the German occupying forces because he was an important authority and held hostage in Sint-Michielsgestel along with six hundred other prominent people. They served as collateral: whenever the resistance shot someone somewhere in the Netherlands, the Germans would shoot some of their hostages in retaliation. It was a terrible time, but Sint-Michielsgestel was liberated in 1944, and Feith travelled straight through enemy lines to return to his beloved city of Groningen.

After Groningen was liberated, he went back to the court and was appointed president of the Groningen Chamber of the Special Criminal Court to practise a totally new form of criminal law. He also held a seat on the committee to cleanse the university: suspending or discharging collaborators. Feith worked days, nights, and weekends to ensure the political delinquents received a proper trial.

‘Finding a balance between the punishment and the severity of the crimes committed [took] an almost superhuman effort’, the judge said shortly before the Groningen Chamber was closed on July 1, 1949.

Terug‘Student and traitor’

Jan Albert van der Warf

Jan Albert van der Warf studied at the University of Groningen before the war and lived with his mother. She picked out his clothes for him every morning, but it didn’t help him enough to obtain a degree at the university.

So, in 1940, when he was thirty-nine years old, he tried to talk to his professors at the faculty of law about getting a degree, but they refused to help him. A friend recommended he go see the German Security Service, or SD, at the Scholtenhuis, a residence the SD had occupied and used as their headquarters. The person he spoke to there was willing to help him, as long as he did something for the SD in return: listen to sermons by Dutch reformed ministers and report on what they were saying.

Jan Albert enjoyed the assignment, as he loved sermons. He reported on them on a regular basis, which eventually led to a minister being arrested and murdered in Germany.

During Jan Albert’s trial after the war, his mental state was examined. The special appeals court decided his sentence would be reduced by five years because of ‘lack of criminal fault. […] The suspect has been affected by his upbringing, his lifestyle, and the suspect’s and his parents’ world view and mentality. People around him barely consider him normal. It’s possible that he has psychopathic tendencies, which means he’s unable to understand the full scope of his actions.’

Terug‘Fired by the Germans’

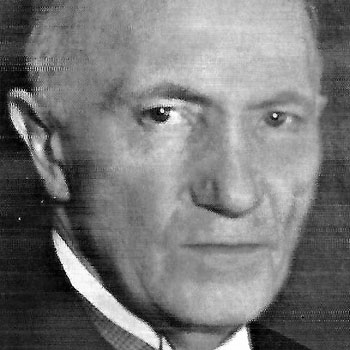

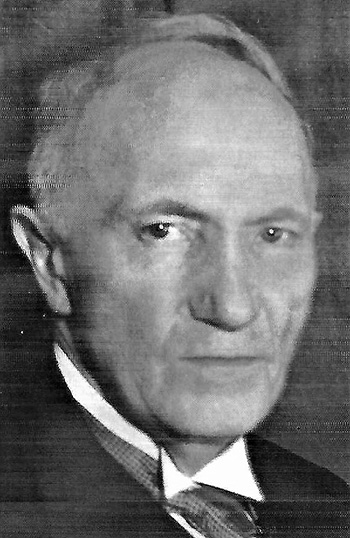

Jan Wedeven (1884-1953)

Jan Wedeven studied law in Groningen and worked as a lawyer. He had a long legal career, and in 1936 he was named justice of the court in Leeuwarden.

In 1943 he and two other justices were fired by the Germans because they had decided a suspect was guilty of the crime he was arrested for, but they’d only given him a sentence that was as long as the time he’d already served waiting for his trial. The justices didn’t want to imprison the suspect in the German camp Erica in Ommen, because a report on the camp had shown that prisoners had been abused and killed and that the prisoners were living in poor physical conditions.

The justices went underground. Wedeven then became ‘judge’ for a secret underground court in Friesland, sentencing traitors to death.

After liberation, he once again became a justice and became the chair of the Special Criminal Court in Leeuwarden until his death in 1953 from a heart attack.

Terug‘Shot by a resistance fighter’

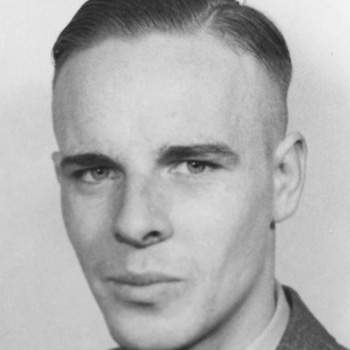

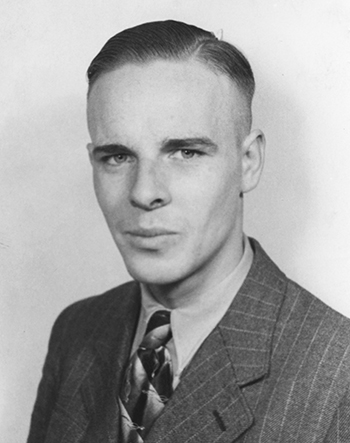

Anne Jannes Elsinga (1908-1943)

Anne Elsinga served as chief of the Special Criminal Investigators in Groningen. This department assisted the Security Service in Groningen, headquartered at the Scholtenhuis.

The Scholtenhuis, also known as ‘the gate to hell’ overlooked the Grote Markt in Groningen and was the scene of terrible abuse. The officers at the Scholtenhuis were tasked with keeping the German occupying army safe. Hundreds of resistance fighters were executed there. Executioners at the Scholtenhuis would often get drunk and go into town to shoot people in the street for fun. Elsinga was extremely active in looking for people in hiding and resistance fighters, to whom he posed a great risk.

He was murdered on New Year’s Eve 1943 by resistance fighter Reint Albertus Dijkema. Dijkema was arrested, beaten, and executed in Camp Vught when he was twenty-four.

The Germans had a policy that when German or Dutch collaborators were murdered, there would be repercussions. So they made a list, consisting of ten names: seven Groningen inhabitants who oppose the Germans and three Jewish people. Six Groningen citizens were shot, the other intended victims went underground. But the Germans also arrested 37 other people; 36 of them were transported to Camp Vught and moved onto concentration camps in Germany. One of them died of a heart attack when he was arrested.

Terug‘The worst kind of war criminal’

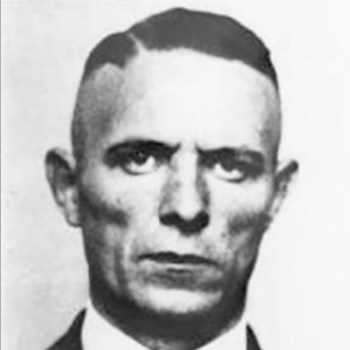

Oomke Bouman (1912-1949)

Oomke Bouman was a Groningen war criminal. He joined the National Socialist Dutch Workers Party (NSNAP) and started working for the Groningen branch of the German Security Service, where he engaged in extreme violence.

He killed several people and introduced one of the most brutal interrogation methods at the Scholtenhuis: repeatedly dunking naked victims into baths of ice water. One resistance fighter died from asphyxiation when he was subjected to this method.

After the war, Oomke Bouman was sentenced to death. His prison guard Willem Langendijk described him as a handsome blond man with a friendly smile and blue eyes that looked at you with sympathy. The night before his execution by firing squad, he was happy and carefree, since a great life was waiting for ‘on the other side’. When the MPs came to get him at eight thirty in the morning, Bouman greeted them with: ‘Oh good, you’re on time. Bye dad, bye mum, bye everyone!’

Terug‘War criminal and charmer’

Peter Jansen Bonnen (and Janna N.)

During the war, Peter Jansen Bonnen worked at the Scholtenshuis and murdered numerous Dutch people in the northern three provinces of the country. He was involved in the shooting of Dutch people from the former detention centre in the night of April 7, 1945, where the Germans killed people without sentencing or trial.

He also participated in the beatings in the Scholtenhuis. In spite of his incredibly cruel nature, he managed to capture Janna N’s heart. Janna’s husband had been sent to Germany to perform forced labour. Janna went to the Scholtenhuis to try and get him back; Bonnen heard her appeal and during the meeting the two fell in love. They moved in together after just a few dates.

Janna’s husband sent her a letter that he’d fled Germany and that he was hiding in Haren. He was afraid to come home because he thought he would be captured again and asked his wife to visit him at the address he was hiding at, which he included in his letter. Janna and Bonnen didn’t want him to come home and wreck their happy life together, so Bonnen sent several SD soldiers to the address in Haren and Janna’s husband and the person hiding him are murdered, as well as a student who was hiding in the same house.

After the war, Janna N. was sentenced to life imprisonment, while Bonnen was extradited to Germany.

Terug