Waiting tables and caring for the elderly

The robots are coming

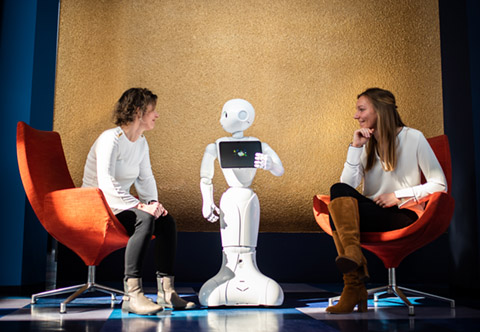

‘Hello, I am Pepper. How are you?’ says Pepper when Jenny van Doorn switches her on.

The white, humanoid service robot stares blankly ahead, her big, black eyes wide open. She holds an iPad close to her chest. I’m not sure what to do. Won’t I look stupid when I start to talk to a robot?

The marketing professor hands me a paper with some short sentences on them. ‘These are things you can ask Pepper. Would you give it a try?’

‘Tell me about yourself’ I say. Pepper’s mouth doesn’t move, but her eyes light up white-blue and she starts to speak: ‘I am a robot.’ Next question: ‘Are you going to take over the world?’ The answer: ‘The only thing I am going to take over is your heart.’ And indeed, in a way, Pepper, at 1.20 metres tall, is quite cute.

Then it’s time to take her to Van Doorn’s office. That means pushing her towards the elevator and through a long corridor. ‘Pepper can move on her own, but she’s incredibly slow’, Van Doorn explains. ‘Moreover, the electric motors propelling Pepper overheat easily on longer distances.’

Unavoidable

These are problems to be solved later, though, she says. To Van Doorn and her PhD student Jana Holthöwer, other questions are much more important. For example: how do humans and Pepper interact? And how can robots contribute to society, while not necessarily replacing us?

Van Doorn and Holthöwer think that it’s unavoidable that robots will be needed in the future. ‘Of course, you always have a lack of personnel in certain fields and that might be solved by robots’, says Van Doorn. ‘But there are also situations where people would rather interact with a robot than a human being, like when they’re buying medication for embarrassing conditions.’

Robots don’t get tired when you ask the same thing over and over

There are already a few places where you can see robots like Pepper. Van Doorn: ‘The sushi restaurant Imono in the Gelkingestraat uses them to take orders from customers, and at Eindhoven Airport people can ask a robot for directions.’ Those are exactly the kinds of situations in which robots can be useful, Holthöwer adds. ‘They don’t get tired when you ask the same thing over and over.’

Covid led to another boost in the use of service robots, according to Holthöwer. ‘In Hamburg, robot carts brought food to Covid patients, and in Japan, robot dogs asked people in parks to maintain a safe distance.’

Limited

There’s still a long way to go, though. Apart from the effort to move them, there’s the price. ‘Even an older robot like Pepper cost about 20,000 euros – the price of a mid-sized new car’, Van Doorn says, ‘while the things they can do are still quite limited. Also, if you want to use a robot for a specific task, taking orders in a restaurant for example, the robot needs software written especially for that job. That’s not something you can easily do at home.’

Despite these issues, robots are being looked at as a solution for the problems with elder care. ‘They’re in dire need of extra staff’, Van Doorn says. ‘Not only because of the current personnel shortage, but also because people are getting older and older.’

Therapeutic robot seal PARO is there to give elderly people extra attention, lightening the load of care workers. ‘The same way a pet does, but without such disadvantages as eating and pooping.’ PARO is low maintenance and has easy technology. ‘On top of all that, he looks cute.’

Uncanny valley

As it turns out, looking cute is really important. If we want to make robots work in the future, we need to know what people respond to when interacting with them, Van Doorn explains, as well as what we want to use them for and how we want them to ‘talk’.

‘For example, how a robot should look depends on the type of task it performs. In restaurant settings, people do not appreciate a very human-looking robot. It either annoys them or scares them off.’

A very human-looking robot either annoys people or scares them off

The term for that is the ‘uncanny valley’. People don’t mind a robot that looks like a machine, many scientists believe. But a robot that looks and speaks like a human but is still clearly distinguishable as ‘fake’ scares people off.

It might very well be that this becomes less of an issue when people get used to robots, Van Doorn thinks. But there are some features all researchers agree a robot needs to have to be accepted. ‘It should be smaller than a human’, Van Doorn says, ‘to emphasise that people still have control. That’s why Pepper is only 1.20 metres tall.’

Easy to ignore

Another matter is this: are we willing to listen to what a robot tells us?

In June 2021, Van Doorn and Holthöwer performed an experiment in the Duisenberg building at Zernike. ‘We moved Pepper to the entrance, near the hand sanitisers’, Holthöwer says. ‘We wanted to know how many people would use the sanitisers when Pepper was asking them to, as opposed to a human steward.’

The results were unsurprising. ‘A robot is easier to ignore than a human being’, says Holthöwer. ‘We found it worked better to let Pepper ask on behalf of the university.’

Uncomfortable

Robots won’t be of much use performing tasks like these, the researchers think. But according to their latest research, they can be beneficial in other areas. What if you use them in a shop selling plus-sized clothes, Holthöwer says, or specific medication? In short: in situations where we might feel uncomfortable? ‘When we feel criticised by others, people don’t always want human interaction. You already see that with the rise of online pharmacies.’

Holthöwer asked participants to get a product from a store that was either embarrassing or not at all. Sometimes Pepper would take the order, and sometimes a person would.

People don’t always want human interaction

‘The results showed that people that had pick up a highly embarrassing product, such as a chlamydia test or a sex toy, preferred to do so at a store where Pepper took the order. But with hand cream or a fitness ball, they preferred human interaction.

That knowledge can be helpful in real life, Van Doorn says. ‘What if people in an embarrassing medical situation refuse to talk to a human pharmacist and leave? Then it may be better for their own well-being if they can talk to a robot.’

Job creation

Developments in the use of robots will go fast in the following years, they expect. ‘But I don’t think we have to be afraid that robots will take over our jobs’, Holthöwer says. ‘In elder care, robots are really an addition, giving elderly people extra attention. In restaurants, robots can take over jobs such as cleaning tables and bringing plates. Human waiters can then put more time and effort into talking to customers and providing service. And of course, jobs are created when people need to maintain these robots.’

However, as we will interact more with robots, it might also influence our relationship with humans, Van Doorn thinks. ‘I see that people interact very rudely with Alexa and Google Home sometimes. One of the dangers is that this behaviour spills over to human-human relations, that you start dehumanising other humans. But I don’t think there is solid research done in that area, so we can’t tell if this is truly a thing yet.’