Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

The story of Piet Mondrian

The oddball who painted joy

The appeal

Why do people love Mondrian’s work so much?

Is it a coincidence that the very first drawing ever made, 74 000 years ago, consists of seven black lines painted on the wall of a cave? It was discovered only two weeks ago. Yet, Piet Mondrian too used straight black lines to depict another universe behind the one we live in. His ideal world.

‘There’s something about straight lines’, Nick Weber, who was awarded his PhD for his biography of Mondrian, muses. ‘There’s a certain quality in Mondrian’s works, that offers relief from the discordant, the upsetting. His designs are immensely satisfying.’

Weber was only twelve years old when he saw his first Mondrian. Of course he had never heard of the abstract painter. He had no idea that the painting that so caught his attention was Composition in Blue and White, the very first abstract painting ever purchased by an American museum.

Weber was only there because his mother’s work had been awarded an honorable mention and would be displayed in an exhibit at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. She took her son along. ‘Of course I was restless; I was not in love with the idea of all my parents friends clucking over me. I asked my father if I could wander upstairs.’

Fifteen minutes later he dashed back down, exhilarated. ‘Daddy, you have to see this!’ That initial moment of shock, of breathless discovery, has never left him. ‘This painting took me somewhere else. I thrilled to it. It was as primal as the first time I ate a banana split, or the first time I heard a piece of music that I really liked’, he says.

This painting took me somewhere else. I thrilled to it

Even at that tender age, he saw what Mondrian wanted to reveal. ‘He was looking for another universe, another way of seeing. A composition that would have qualities of rhythm, joy, euphoria, satisfaction, pleasure. Pleasure untainted by anything else. There is no possibility of death: what you see in his paintings is going to last forever.’

The myths

What do we really know about Mondrian?

A lot of ink has been spilled trying to unravel and interpret Mondrian’s life and work. But Weber is trying to do something new with his biography. He only used primary sources for his research. ‘I only write what we know’, he says. ‘No one has any business misrepresenting another person. A biographer should be meticulous.’

To enter Mondrian’s universe is to encounter a singular form of beauty. No one else lived like this, and no one else painted this way. Many imitated his style, some of his contemporaries copied him, and in time the motifs he invented would appear on dresses and ladies’ shoes, from discount stores to haute couture, just as his name would be used to confer a certain panache on hotels and apartment buildings, but none of that was the same thing. The artist’s existence on rue du Départ, and the art he made there, harnessed manic enthusiasm with exquisite control, both at their extremes. Most people live by half-measures, or follow someone else’s ideas.

Mondrian had created, in his rudimentary living quarters and bright airy work space, a private sanctuary, suited only for its sole inhabitant. What to others would be selfdenial was for him the pathway to nirvana. Possessed by the fierce determination of a messiah, but with none of the self-consciousness of most messianic types, he used the ideal life he had created for himself to make paintings which, even when physically small and with their elements distilled to a minimum, became secure and uplifting worlds of their own.

From: Piet Mondrian’s early Years. The winding path to straight abstraction, Nicolas Fox Weber

And so Weber talked to the few people who had known Mondrian, the man – including his art dealer. Weber read archived letters from his family and first-hand accounts written by the few friends who were intimately acquainted with the artist. He began to see that history had been unfair to Mondrian.

‘For example, there’s an oft-repeated story that he skipped mother’s funeral, even though he lived nearby, because he was busy with an exhibition. That is almost pathological; it coloured my perception of him: what kind of human being does this?’

Sexual preferences

But then Weber found a letter by Mondrian’s brother that explicitly mentions the artist’s presence at the funeral. ‘That made me furious. People repeated that story, but no one asked about the evidence’, Weber says.

There has also been a lot of speculation about Mondrian’s sexual preferences. Was he a homosexual? According to accounts of his aquaintanecs, he once broke off an engagement and otherwise seemed unable to maintain romantic relationships for long.

Also a bit odd: one female friend gave an account of a make-out session with the artist that lasted for twenty minutes – she kept an eye on the clock. But Weber refuses to speculate. ‘I tell these stories, but leave it to the reader to draw his own conclusions.’

The personality

Who creates such extraordinary paintings

All the same, records of Mondrian’s behavior did leave the researcher with an impression that there was something off about the artist. Weber calls him ‘a bit of an oddball’ who had little regard for expected social norms.

‘I talked to Ben Sanders, whose father was among Mondrian’s acquaintances. When he was ten years old he went with his mother to see “Uncle Piet” in Paris. He remembered that when they entered the atelier, Mondrian didn’t even say hello. He just said to the mother, “will you dance with me?” They danced for half an hour while the boy watched. Then they left.’

It’s not speculation to call that odd behavior, Weber says. There are other stories: Mondrian attended many social events, but always kept to himself. When he was young, he was obsessively afraid of damaging his eyes – so much that he didn’t play with his brothers in case he might wound himself.

He was hysterically afraid of spiders – he once fell asleep during a concert; upon waking up his saw a spider and started screaming at the top of his lungs. He often broke off friendships; he never married; he never maintained any close relationships.

I think abstract art made him happy; to create a beautiful, visual universe. He lived in a world of pure lines

He cloistered himself in his studio, but not for lack of invitations. He ate every meal alone. All he did – and all he wanted to do – was paint. Is that sad? ‘I think he connected the way he wanted to’, Weber says.

‘This life suited him. It wouldn’t suit most of us, but it worked for him’ because it allowed him to focus on his work. He didn’t worry about money or fame – he only worried about the world at his fingertips. ‘I think abstract art made him happy; to create a beautiful, visual universe. He lived in a world of pure lines.’

The road to abstraction

Why did Mondrian go from landscapes to straight lines?

Too many people see Mondrian’s life as a timeline divided. On one side of the line is the young representational artist painting trees and dunes and sunsets, who learned all the classic principles of the The Hague School and worked alongside his uncle Frits – a painter who depicted living landscapes and sceneries exactly the way his customers liked them.

One very odd memento, however, augments our impressions of Mondrian in 1900. That year, he made a self-portrait. A few years after he painted it, Mondrian and the youngest brother of Albert van den Briel, a cadet at a military academy, keen about modern automatic weapons, was doing some pistol shooting with Mondrian in the basement of the building where Mondrian lived in Amsterdam. They generally used Mondrian’s discarded canvases, all of them failed portraits, as targets. The two men started firing. ‘Piet was a good shot; his hand was steady,’ Van den Briel tells us.

‘When all the portraits had been used, there was only that self-portrait left, and Piet wanted to shoot it too.’ He was determined to obliterate the canvas by riddling it with pistol bullets. Van den Briel’s brother objected, however. He told Mondrian that Van den Briel would be upset. ‘Besides, they were running out of ammunition.’

Mondrian then gave the painting to the brother to give to Van den Briel, saying ‘that it was an insignificant thing, made only to solve a technical problem—that of making the sitter’s eyes always meet the spectator’s.’

From: Piet Mondrian’s early Years. The winding path to straight abstraction, Nicolas Fox Weber

On the other side of the line is the brilliant abstract artist who fled to Paris, the man who meticulously avoided the ‘tragic’ – as he called the natural world – and carved out a totally new reality. ‘But I don’t see his life as divided in two’, Weber says. ‘From the beginning Mondrian was attracted to something universal. He just hadn’t found his language yet.’

His lifelong quest is visible from his beginnings. He became a fairly appreciated painter after he left school. But Mondrian also began experimenting with new techniques and ‘odd’ subjects, which earned him harsh criticism at one exhibition after another.

Mindless

The still life of a herring in 1892 offended the critics – couldn’t he have painted something prettier? Critics accused him of ‘lack of poetry, lack of mood’. At a 1909 exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, they said his art was ‘simply mindless. The work of a child indeed: a sick, rebellious child with a few pots of paint to hand’.

His uncle Frits was so enraged his nephew’s discomfiting style he demanded that Mondrian drop the second ‘a’ from his name. He didn’t want anyone to associate him with his now ‘depraved nephew’.

But now we can see how Mondrian was changing and experimenting to reach his goal with every new attempt. ‘He was gradually refining his art’, Weber says. ‘And he was developing, as most great artists do. There is no inconsistency here, only different stages with Mondrian always trying new things.’

Mondrian kept trying new things, says Weber, even late in life. Slowly but surely, Mondrian stopped painting reality as we see it and found ways to represent the vast universe beyond sense perception. ‘The criticism only strengthened his mechanism of self-protection’, Weber states. ‘It increased his resolve and tenacity and his will to follow his own beliefs no matter what.’

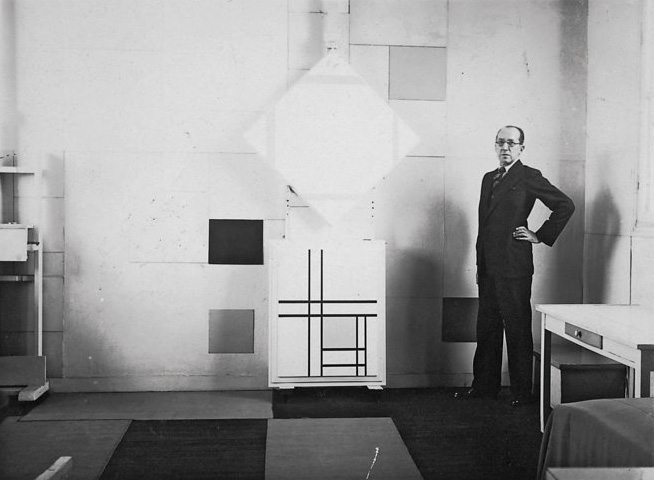

Photo Mondrian by Charles Karsten. Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut.