Maaike Muller’s travelling installations

Science for everyone

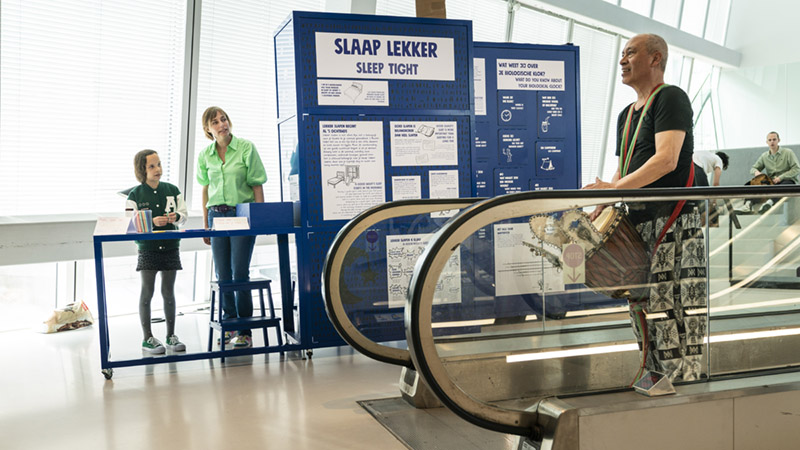

What happens when you sleep? How do you ensure you get a good night’s sleep? Why are some people early birds and others night owls? Over the past few weeks, her eye-catching blue installation piece at the Forum would answer these questions: visitors could even have a lie down while being educated.

The Slaap Lekker (Sleep Tight) installation, which has since moved on to the library in Sneek, is meant to playfully teach people about how to improve their sleep. Maaike Muller, public engagement programme manager at the Aletta Jacobs School of Public Health, has made it her mission to bring health research to the people so it can actually have an effect.

The School is a partnership set up by the UG, the UMCG, the Hanze University of Applied Sciences and NHL Stenden and intends to ensure that people live longer and healthier. According to the RIVM, highly educated men, on average, live 6.3 years more than their counterparts with limited education; in women, the difference is 3.9 years. The difference in healthy years is even bigger: people with limited education of either gender will start suffering health issues approximately fourteen years earlier.

‘A lot of policy has been written to try and do something about this, but the problem hasn’t been solved yet. That doesn’t seem fair’, says Muller. She wants to do something about it.

Healthy choices

She knows it isn’t easy for people to change their lifestyle. After all, not everyone has the means to make healthy choices. ‘It’s important to keep that in mind when trying to tackle this form of health inequity’, she says. ‘At Aletta, we want to get rid of the notion that people are entirely responsible for their own health.’

We want to get rid of the notion that people are entirely responsible for their own health

She says that scientists need to understand what people think is important. ‘If you’re doing research to improve people’s health, you have to try and understand your target group’s situation. We all know that a carrot is more important than a French fry, and yet many people pick the fry. Why?’

Interactive installations such as Slaap Lekker are her attempt to bring scientists and the public in the north of the Netherlands closer together. ‘That’s the most important aspect of my work: to convey knowledge equally to both.’

Exhibition

When Muller started at the Aletta School three-and-a-half years ago, they asked her to make two installations, but her ambitions were bigger than that. ‘I love applying a public engagement strategy to cases like this, because it will enable me to continue building on things I make today.’

Together with an exhibition designer, she created the exhibition Chronisch Gezond (Chronically Healthy), which consists of various installations that have been separately travelling around the region. ‘I love bringing science to places people don’t expect it, so they can just sort of come across it’, says Muller. ‘The installations often achieve that.’

In order to appeal to a wide audience, the installations always contain interactive elements. In the installation Schep Maar Op (Dig in), you can play a game in which you have to race through a supermarket. Or you visit a snack wall, where you can open the little doors to hear people’s opinions on the sugar tax.

Interested

She loves seeing people enjoy her installations. She once went to a festival with suits that made people’s bodies feel old. ‘Children were crying with laughter because they suddenly couldn’t get up from a chair.’

I want to convey knowledge equally to both the public and scientists

Nevertheless, it’s always a tense moment when a new installation is revealed. ‘You can only hope that it’ll work’, she says. There’s no reason for her nerves, though, because passers-by usually start to get interested as soon as they start building. ‘With good reason: the installations are really big and brightly coloured.’

However, things didn’t quite work out for Muller’s very first installation, although it wasn’t for lack of interest. It was called Klein Venijn (Small but Nasty) en was about viruses and bacteria. It was first set up in the Forum, the first stop of most of her installations, but was only open to the public for a single day. ‘Ironically, it was a virus that ended up shutting it down’, she says, laughing.

That was the first Covid lockdown. ‘It was a complete coincidence that we’d picked that theme. We just a had a really enthusiastic scientist in that particular field and I figured it would be a good idea to start with that energy.’

Learning experience

After a few weeks in the Forum, the installations travel through the north of the Netherlands, to schools and libraries. Muller depends on funds to finance everything. Some of them are paid for by the EU. ‘Some locations can afford a contribution, which is great, but schools usually don’t have the budget. So we have a little fund to help them out.’

At one point, Muller got a phone call from a high school student who was working on a project about sugar. ‘She’d seen the Schep Maar Op installation at the Forum and was wondering if we could come set it up at her school. It made me so happy to be able to arrange that!’

Everyone should feel free to make their own choices

A lot of students help create the installations, says Muller. They’ll go to neighbourhoods to talk about people or design parts of the installations. But they can also be found on site with the finished installations to talk people through them. ‘I hope it’s a great public engagement learning experience for them and that they’ll use their experiences in their future workplace.’

To test whether the information the installations are supposed to convey actually comes across and sticks with people, Muller also collaborates with the UG’s Institute for Science Education and Communication (iSEC). They do impact studies by observing visitors and asking them questions. ‘We can learn from that and adjust our installations where necessary.’

Her goal for the future is to change people’s way of thinking. People complain so much about everything that’s wrong with the world, she says, and she wants to know what people do want to see? While a lot has to change when it comes to public health, energy, and the climate, Muller says, ‘those decisions shouldn’t just be made by policy makers and scientists. Everyone should have an opinion on these issues.’

When it comes to people’s health, it’s important to strike the right chord, she says. In her conversations with people, Muller has noticed how some people will talk animatedly about everything they’re doing to stay healthy, while other people feel like they’re being held accountable. ‘You have to be careful how you talk to people. You don’t want to patronise them.’

After all, she says, health is a very personal issue. ‘Everyone should feel free to make their own choices.’

That’s what her installations are for: to make information accessible without judging people. ‘I think it’s very important to make science fun and show people how it can impact their future. And then they can decide for themselves what they want to do – or don’t want to do – to stay healthy.’