Odisha, India

Where dying can take a generation

Some researchers get lucky. They don’t end up in the basement of a grey laboratory, on a shared desk. No, their work spaces look more like a holiday resort. This week part 5: Odisha.

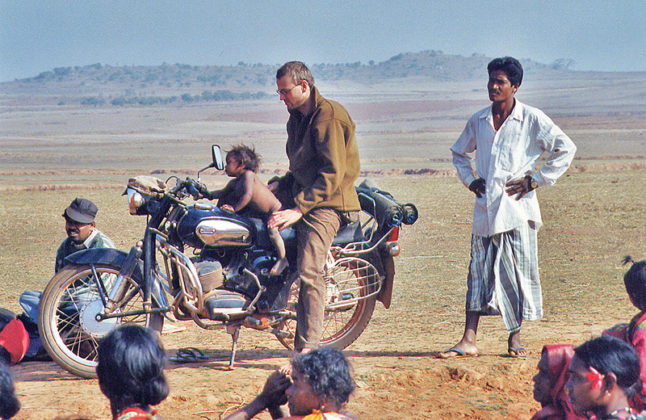

Some researchers get lucky. They don’t end up in the basement of a grey laboratory, on a shared desk. No, their work spaces look more like a holiday resort. This week part 5: Odisha.Anthropologist Peter Berger was still a student when he ended up in Odisha, in the eastern highlands of India. He went to study the remarkable death rituals that the Adivasi tribes are known for. He ended up staying for years – and even got married there. He still studies the fast-changing tribal culture and its singular ritual use of food.

‘It wasn’t a culture shock, when I first arrived there. I mean, things were different of course, but you expect them to be. That was the whole point of becoming an anthropologist in the first place. I wanted to really understand other cultures, dig deep, and challenge my own perspectives.

Koraput, the district where I lived, is very remote, situated in the highlands where the rivers flow so slowly that the people have turned them into rice fields. You see these vast green rivers and hardly any trees. In fact, when you see a group of trees – mango, tamarind or jackfruit – you know a village, with its mud houses and grass topped roofs, is probably located there.

Water buffalo

I came because of their famous death ritual. In this society, death is a process that can take a generation. After people die and are cremated they are not really considered dead; their spirits are still around. After a certain period a ritual is performed and their soul is transferred into a water buffalo by a shaman. You actually get introduced to this buffalo as: ‘This my father, or brother, or sister.’ The buffalo is fed, gets beer, everything, until finally it’s brought to a memorial location, where it is killed and the soul is released. A person is not really dead until that happens. But because the ritual is expensive – for every person a buffalo gets killed – they often postpone it. It takes place roughly every 25 years.

In the past, anthropologists came just to study this specific ritual. But I wanted to do more, dig deeper. I wanted to know how this ritual was embedded in their culture. So I asked to stay.

Low status

At first they didn’t really know what to think of me. I was probably a tourist, because I was white. So they housed me with a guy who organised village dances for Western tourists on ‘tribal tours’. He had a small shed for the water buffalo and made a wall in it, so I shared a roof with the buffalo. Later on, when they knew me better, I came to live with an old widower. He would sleep on the veranda. That was actually quite normal. Old, especially widowed people sometimes don’t have their own houses and old people don’t have a very high status.

One time, when a very old woman had a bad cough, I went out on my motorcycle and bought some medicine for here. People asked me: “Why are you wasting money on such an old woman?”

Food rituals

While learning the language, working in the fields, and experiencing day-to-day life, I found that food – even though their culinary ways are very plain – was extremely significant. It is part of every important stage of life. When a baby is born it is not even considered a person until a feeding ritual has taken place; it’s symbolically fed a little rice to make it grow into a person. The high point is when you get married – you are fed by four or five different people, which makes you a full-fledged member of the tribe. I took part in that ritual, myself. They kept asking after my wife and when she visited, the villagers had already started a wedding ceremony for us.

Even sickness is seen as food-related. An evil demon is ‘eating you up.’ A healer will try to turn the tables by devouring the attacker. And finally, when you die, you are slowly fed out of the community.

The highlands are very different now than when I first arrived over 25 years ago. Back then there were mainly mud houses and no electricity. People would gather around the fire in the evening. And it was so quiet! Now? There’s music and television and the younger people want to live in concrete houses. The place looks like a construction site. The vibe is totally different. However, I don’t think of it as a bad thing. Cultures change all the time. But it is a very interesting process to study.’