Groningen’s first Holocaust victim

‘His death saved his life’

Leo Polak became a professor in the philosophy department of the RUG in 1928. His field of expertise was philosophy of law and the principle of retribution.

Although he himself was Jewish, he was an iconoclast and was a leading humanist in the Netherlands.

When Jewish staff members were placed on non-active status in late 1940, Polak wrote a series of letters referring to the German authorities as ‘the enemy.’

As a prominent Jewish intellectual in the Netherlands, Polak was already seen as a threat to the Germans. But when rector magnificus of the university at the time, Johannes Kapteyn, turned Polak’s letters in to the authorities in early 1941, they were used as grounds to arrest the professor.

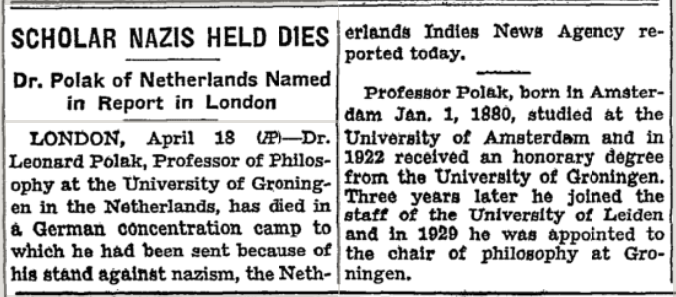

He died at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany in December 1941, a facility which was primarily filled with political prisoners.

Polak was one of the first Jewish people from Groningen to die in a concentration camp, but his legacy survives at the RUG in the form of an honorary chair and in his depiction on one of the stained-glass windows in the aula.

Reading time: 7 minutes (1,138 words)

Why did one of the preeminent newspapers in the world report on a Dutch professor’s death? It may be because Polak’s life could just as easily have not led him to a German concentration camp, but rather to New York City.

On 6 December 1940, the Dutch scholar received a standing invitation to come and teach at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan. Since 1933, the private university had explicitly sought to provide safe refuge for Jewish European researchers through an initiative called University in Exile.

‘Too late’

The offer even included visas for his family members. But if Polak took any steps to accept the invitation, according to law professor Jeroen ten Voorde, it was already too late. ‘He hesitated too long. When he finally realised he had to go to the United States, the Netherlands were occupied and he was not able to leave the country anymore’, he says.

Even though Polak clearly saw and regularly identified the threat that Hitler and National Socialism posed, it seems that Polak’s connections to Dutch society made him reluctant to leave. He was something of an academic celebrity: he was a public intellectual in the Netherlands and made frequent radio show appearances. But in his private life, Polak was a fairly solitary figure and counted few friends among his colleagues at the RUG.

‘Philosopher of free thinking’

Polak was raised Jewish, but was openly critical of all religions. He was the chairperson of the Dutch Atheists Union at one point. He was a philosopher of law. He was a humanist. He explored topics like sexual ethics, free will, retribution and criminal punishment and its origins in Abrahamic religions. He is best remembered by history as a leader of the free thinkers movement in the Netherlands. Reason, science and logic were his personal pillars.

He was a graduate of the law faculty of the University of Amsterdam and became an honorary professor of philosophy and law at the University of Leiden in 1925. Three years later, he succeeded Gerard Heymans (after whom the building housing the Faculty of Behavioural and Social sciences is named) to become professor of philosophy in Groningen.

Those personal and professional details – and how his life very nearly could have been saved – were revealed in the book, ‘Leo Polak (1880-1941), Filosoof van het vrije denken’, based on 40 years of meticulous journal entries kept by Polak, from 1901 to 1941.

Warning

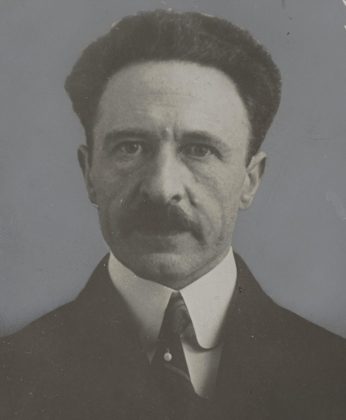

Leo Polak in 1925. Polak is visible on one of the panes of stained glass in the aula: His face is featured on the far right side, just behind Heymans.

He saw fascism coming and warned against the rise of Hitler. In the 1930s, Polak was a member of the anti-fascist Committee for Vigilance. He also provided shelter to German Jewish refugees in the early years of the war. The combination of his anti-establishment statements in public and his Jewish identity made him ‘the most dangerous Jewish person in Groningen’, according to assistant history professor Stefan van der Poel, co-editor – along with history professor Klaas van Berkel – of ‘Filosoof van het vrije denken.’

Ten Voorde admires the man after whom his honorary chair at the RUG is named for never taking the ethical underpinnings of criminal justice for granted and for remaining inquisitive throughout his academic life. Yet he is not as eager to enter the realm of public debate as Polak was. He recently declined to make an appearance on Nieuwsuur to discuss the trial of Geert Wilders and his alleged hate speech. ‘If I were to say something critical about Mr. Wilders, I knew I would receive threats. But Polak did not hesitate to enter public debate and say critical things about religion at the height of pillarisation. He always argued that religious beliefs were meant to be private, not public.’

Inaction

‘I think that his death saved his life’, Van Berkel says. In other words, the manner in which Polak died – in a German concentration camp – drew attention to the scholar’s work that may not have existed otherwise. Even among those who are familiar with his name, his position as a professor at the University of Leiden before coming to Groningen is barely known at that university, another commonality shared between Ten Voorde and Polak.

The story of at least one Jewish professor there is in stark contrast with Polak’s treatment at the RUG. When professor E.M. Meijers was relieved of his duties in November, his former student and professor Rudolph Cleveringa gave an impassioned speech in defence of his advisor. In Groningen, Polak’s eventual arrest was met with no apparent resistance. There is also no evidence of any formal request by the university for Polak to be released from German custody.

A lack of effort by the institution to save the professor can be explained with disturbing ease: it was the rector of the RUG at the time who almost certainly sealed his fate. Johannes Kapteyn, a professor of German language (not to be confused with the astronomer Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn, the namesake of a RUG institute and a street in Groningen), was appointed rector in September 1940 by the Dutch authorities under pressure from the German authorities – against the recommendation of the Academic Senate at the time.

Shut out

By 1 December 1940, all Jewish public servants – including university employees – had been placed on non-active status. Polak got the phone call on 22 November informing him that while he could keep his title as professor (and his income), he would be relieved of his duties. He was no longer allowed to teach, was not invited to faculty council meetings and was not informed of upcoming PhD defences or orations.

Being deprived of his connections to the academic community ‘was more painful to Polak than the average professor’, van Berkel says. ‘He truly came to life when he was before an audience.’ And he did not take that news sitting down. He immediately wrote to the university’s governing board (College van Curatoren) and the leaders of his own Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, referring to the Germans as ‘the enemy’. Polak alleged that the powers-that-be were like a dog ‘on a leash’ that was ultimately held by Germany.

Rector Kapteyn smuggled Polak’s letters out of the faculty in his coat pocket and provided them to the German authorities. Although Kapteyn would later claim that he went to the authorities seeking advice on how to handle the contrarian staff member, the letters were used as grounds to detain Polak, even though Polak was never formally charged with any crime.

Political prisoner

On 15 February, the professor was arrested and brought to a prison in Groningen. On 15 March, Polak was taken to Leeuwarden, where he was held for months. By August, he had been relocated to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp near Berlin, a facility that primarily held political prisoners. He died on 9 December 1941 from exhaustion, exposure and starvation. He was one of the first Jewish people in the city of Groningen to die in a concentration camp, 75 years ago this week.

It took the university 25 years to publicly acknowledge how Polak’s fate was sealed by his own rector. There was a remembrance ceremony in honour of the late Jewish professor in 1966, when then-rector Eduard Herman s’ Jacob described his predecessor’s actions as part of ‘a shameful period’ in the university’s history.

In 2005, rector Doeko Bosscher stated in no uncertain terms that the university should be ‘deeply ashamed’ of putting Nazi sympathisers into such prominent positions at the RUG – not only Kapteyn, but also his immediate successor, Herman Maximilien de Burlet, who was an NSB member. Bosscher asserted that the university as an institution did too little to free Polak from the hands of the Germans.

Presence

Although Kapteyn’s actions and the rest of the university community’s inaction led to Polak’s detention and eventual death, the professor’s name and likeness have not disappeared from the RUG altogether. His presence in the Harmonie complex is still evident: Ten Voorde became the first professor by special appointment in Philosophy of Criminal Law, provided by the Leo Polak Endowed Chair foundation, in 2014. A conference and Studium Generale lecture were held last year focusing on the late Polak’s legacy.

And in the towering stained-glass of the aula in the Academy Building, Polak is surrounded by his fellow academics on the window pane depicting the modern history of the university. Despite efforts to shut him out of academia in life, Polak is always present at every PhD defence and oration held in the heart of the RUG.

On 20 December at 20:00, a presentation of the book ‘Leo Polak (1880-1941), Filosoof van het vrije denken)’ will be held at the Folkingestraat synagogue. Entrance is free.