Kant was a sexist

And we have to deal with that

Pauline Kleingeld says it happens all the time. The copy editor of a philosophical journal will return an article to her, having changed every single instance of ‘his’ to ‘his or hers’, and ‘he’ to ‘he or she’, in an effort to make the language as inclusive as possible. She is of course entirely in favour of this principle. ‘The only problem is that it’s often incorrect’, she says. This means she ends up changing everything back.

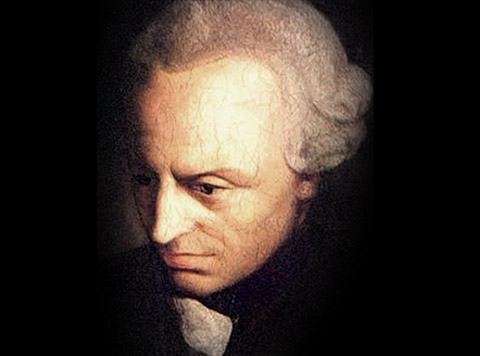

This is what happens when you specialise in the works of famous Enlightenment philosopher Immanual Kant. Kant may have been the champion of individual freedom, human dignity, and absolute morals, but the man was also a sexist. Kleingeld recently published an article on this topic in SGIR Review.

Kant’s ethics applied to all reasonable beings, just not to women

When he wrote that ‘every citizen has the right to vote’, or that every single ‘person’ has a right to independence, he wasn’t referring to men and women. ‘People’, Kleingeld explains, ‘meant men. It didn’t matter where they lived, because Kant’s ethics were universal. It applied to all reasonable beings, even those on other planets. Just not to women.’

He also had quite a few racist ideas, although he reconsidered those towards the end of his life. The ‘white race’, Kant said, was at the top of the racial hierarchy. ‘All non-white races were lacking certain qualities the white race did have’, Kleingeld explains, ‘which means they weren’t capable of governing themselves.’

Who was Kant

Kant is famous for two of his works: ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ (1781) and ‘Critique of Practical Reason’ (1788). In the first work, Kant proposed a new theory of our knowledge of reality. He said that our perception of reality is determined by the way our cognition works. One of the implications of this theory is that it’s impossible for people to know God, a radical thought at the time.

His second book deals with moral philosophy. In it, Kant defends his views on the norm for moral actions. If you want to know if your actions are morally just, you have to ask yourself according to which principle you are acting, and whether you want everyone to act according to that same principle.

In his later works, including ‘Toward perpetual peace’ (1795), Kant developed an influential view of what’s needed to reach world peace. He sharply criticised European colonialism.

Product of his time

Kleingeld is perfectly aware that ideas like these were very common in the eighteenth century. But she thinks it’s too easy to say that Kant is simply a product of his time. ‘He was very good at debating other people’s opinions’, she says. ‘Moreover, he had friends who had different opinions on the matter. His friend Von Hippel even published a book on the need for the emancipation of women!’ But whenever women wanted to debate him on the French revolution, he’d refuse and change the subject to recipes and cooking.

Kleingeld thinks this is revealing. ‘As though he didn’t even want to know he might be wrong. That women were actually capable of reason and didn’t just respond to things emotionally or based only on their “inclinations”.’

The Groningen RUG philosopher, who’s also a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences has been studying the Enlightenment philosopher almost her entire life. It started at university, when she studied Hegel and Kant for an exam. ‘Except I wasn’t finished, and I asked my professor if he could only ask me stuff about Hegel. I’d then write my thesis on Kant.’

Women

After her thesis, she wrote a dissertation on Kant. Now, nearly thirty years later, she’s known as one of the foremost experts on Kantian ethics and philosophy. ‘I gradually became more impressed by his way of thinking’, she says. ‘How he managed to defend his universalist ethics, where he said how it was morally unjust to use others purely as a means to your end. All kinds of emancipating movements were based on Kant, like the anti-slavery movement and the women’s movement.’

But it’s still uncomfortable that the man whose ideas we keep referring to had a completely different viewpoint himself.

The anti-slavery and women’s movements were based on Kant

Take women, for example. ‘The virtue of a woman is a beautiful virtue’, Kant wrote in 1764. ‘That of the male sex ought to be a noble virtue. Women will avoid evil not because it unjust, but because it is ugly.’ And: ‘They do something only because they love to, and the art lies in making sure that they love only what is good. I hardly believe that the fair sex is capable of principles.’

Women are naturally fearful, weak, and passive, Kant said. Since men are naturally more courageous and stronger, it’s only reasonable for them to be in charge. He did think women had many good qualities: they were very good at running a household. And let’s not forget: they were really good at seducing men. ‘He damned them with faint praise’, says Kleingeld.

Slave trade

Kant’s descriptions of other ‘races’ aren’t particularly edifying, either. In his classes – Kleingeld studied unpublished lecture notes – he said that Native Americans were the ‘lowest’ of the four races, because they were weak and impossible to teach. ‘Americans and Negroes can’t govern themselves’, Kant lectured. ‘Thus they serve only as slaves.’ The inhabitants of India were incapable of abstract thinking and were definitely not suited for leadership positions.

When it comes to the slave trade, he is particularly enamoured of the Mandinka people, who he says can handle circumstances no ‘man’ can withstand. ‘Each year 20,000 of this Negro nation have to be bought to replace their decline in America, where they are used to work on spice trees… One gets the Negroes by having them catch each other, and one has to seize them with force.’

Turnaround

How has someone like this been immortalised as a champion of freedom and equality?

It’s partly because of the turnaround he made towards the end of his life, Kleingeld explains. When he was around seventy years old, Kant started to criticise colonialism and slavery. That’s what people remember about him today. Unfortunately, his view on women never changed.

You can’t just leave his words unchanged, that misleading

Kant’s use of language also explains his enduring popularity. The books that made him famous never explicitly say that when he wrote ‘humanity’ he only meant the male half, or only the ‘white race’. ‘I discovered this when I was reading other, less well-known texts that he wrote around the same time’, says Kleingeld.

But now that she knows what he meant she can’t ignore it any longer. We can’t just downplay it and replace ‘him’ with ‘him or her’ in his texts. It’s simply not what he meant. But we also can’t ignore it and leave his words unchanged. ‘That’s misleading.’

Bad parts

Should we just burn his books, then? Get rid of Kant? Absolutely impossible, says Kleingeld. He is one of the founders of modern thinking. ‘If you criticise Kant, you do so on the principles he himself defended’, she says. ‘That alone means you have to give it a lot of thought.’

What we should be doing, says Kleingeld, is find out what role Kant’s convictions played in his theory. ‘You can’t just cut out the bad parts. When he changed his mind on colonialism, he adapted his political theory and came up with ‘cosmopolitan rights’, which grants citizens all over the world legal status. Before that, he just didn’t see the need.’

This means we have to figure out what else should change in order to conquer Kant’s sexism and racism. In other words, Kleingeld has a lot of homework ahead of her. In the meantime, she explains in her notes how Kant really felt about things. It may not be the most elegant solution, but it’s the most genuine one. ‘So be it.’

Translation by Sarah van Steenderen