38 years of research on Cousin

Protector of an island

‘Empty white beaches, the only footsteps I saw were my own. I was surrounded by seagulls, sterns, and noddies, it was amazing! They practically landed on my head. There were even birds and geckos in my house. But in the end, that’s all there is: just you and the animals.’

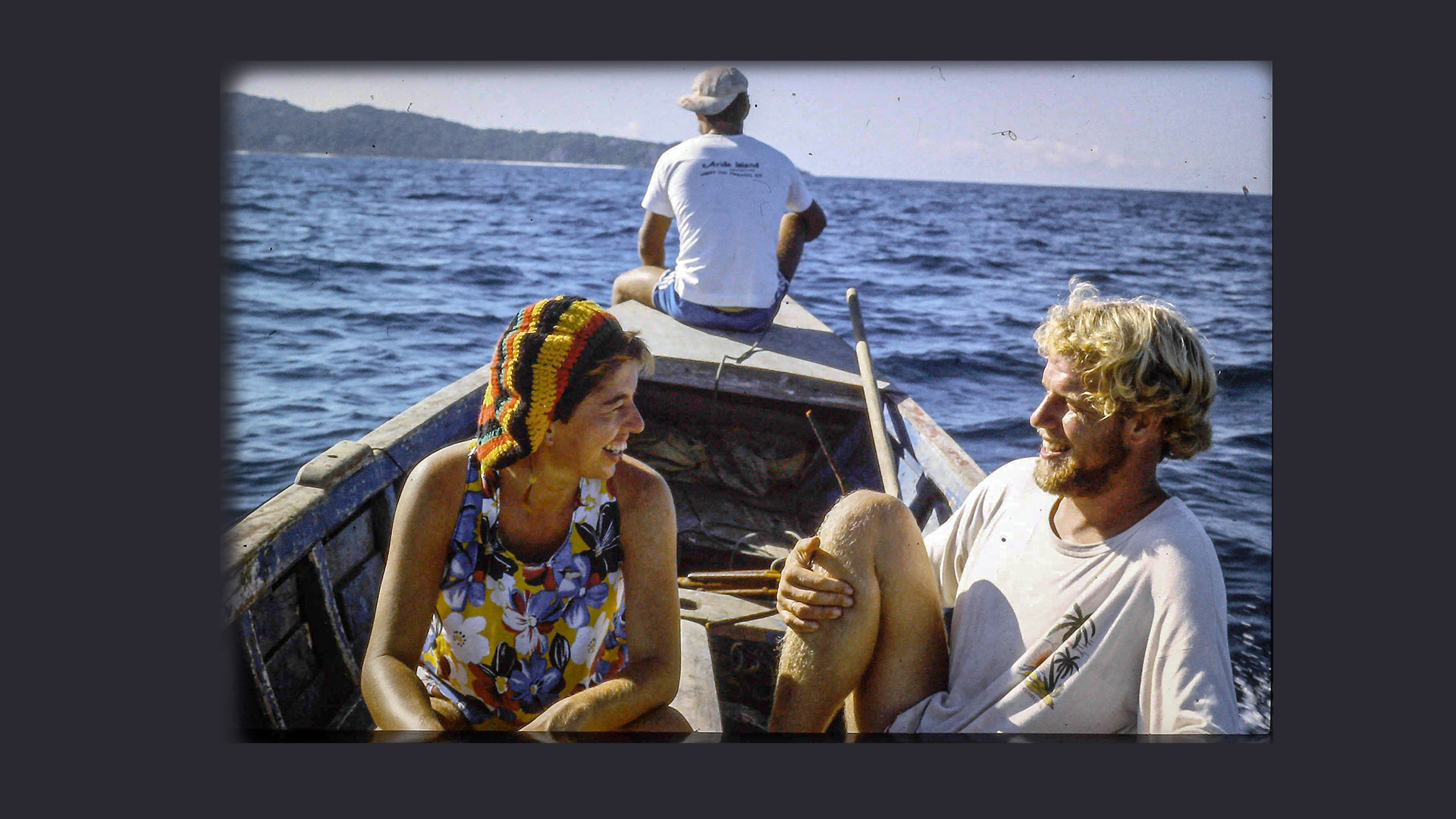

Evolutionary biology professor Jan Komdeur still remembers what it was like when he first set foot on the tropical island of Cousin, one of the islands in the Seychelles, in 1985. ‘My wife and I moved there to live in a coconut shed, which was just four posts and a metal roof.’ But at least that shed was surrounded by pearly white beaches, tropical rainforest, waving palm trees, singing birds, and lizards sunning themselves.

Komdeur had been hired as a warden for the island that, at the time, was uninhabited. His job was to take care of the island, protect the flora and fauna from poachers, and to do scientific research for the University of Cambridge, where he worked at the time.

Endangered

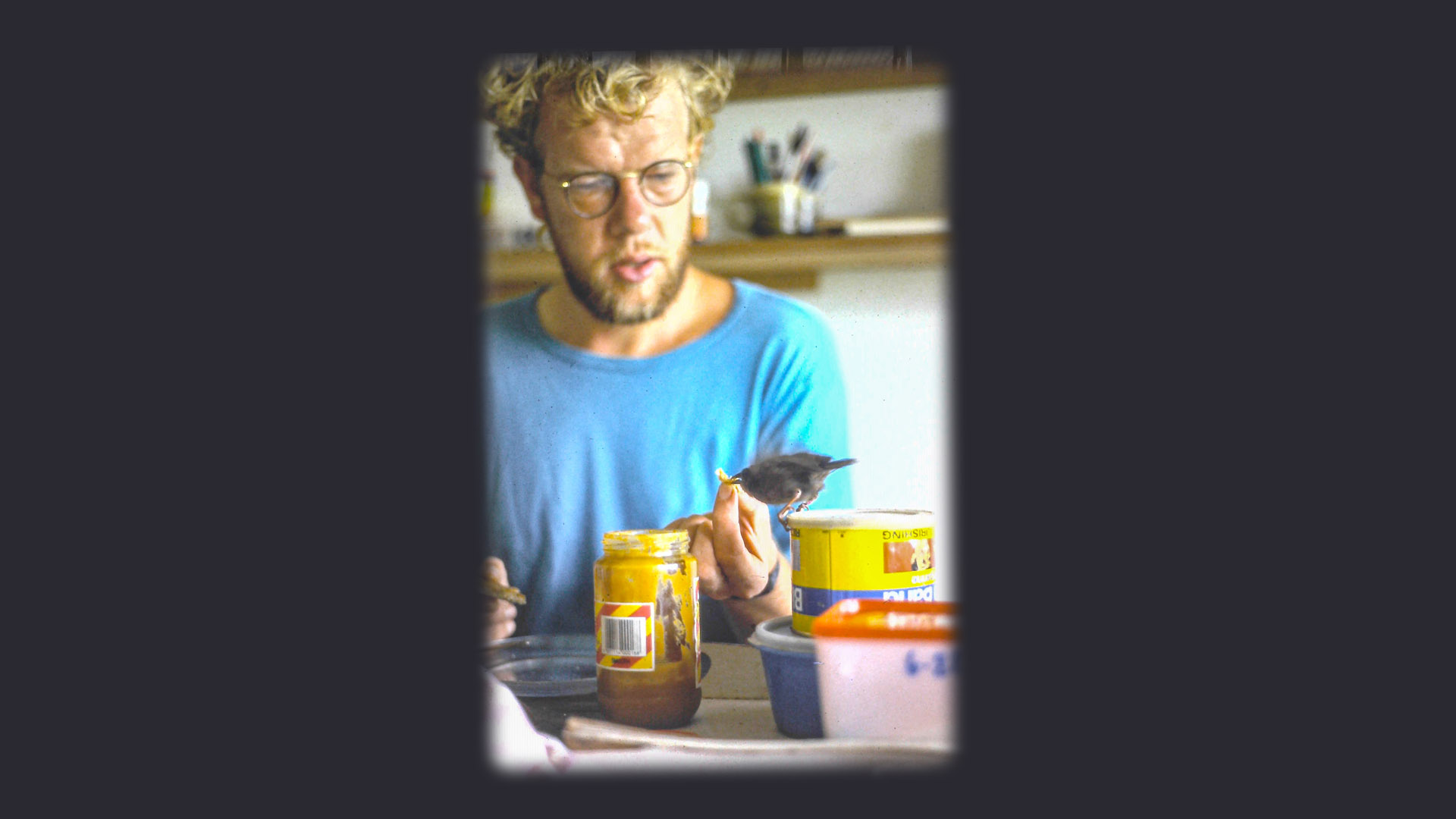

He decided to focus on the social behaviour exhibited by the Seychelles warbler, a small brown bird that back then could only be found on Cousin. Of the three indigenous bird species, this one was the least well-known, and it was endangered to boot. Komdeur found out that the warblers would occasionally get together in groups to brood and raise their young. He thought it was interesting and wondered why they did that.

In the end, it’s just you and the animals

This question ultimately gave rise to what is now officially known as ‘The Seychelles Warbler Project’, a large research project that is going on for thirty-eight years. It’s one of the spearheads at the Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Life Sciences (GELIFES) at the UG. It consists of a group of researchers from all over the world who study Seychelles warblers while simultaneously trying to save the population.

This little bird has had it pretty rough. The last count, before Komdeur started his research, is from 1968, when the island was still a coconut plantation. Back then, there were only thirty birds. In the five years that Komdeur lived on Cousin, he spent a lot of time counting and ringing birds. He also invested time in demarcating the birds’ territories. He counted approximately 320 birds, spread out over 115 territories. Quite a few more than there used to be.

Challenging circumstances

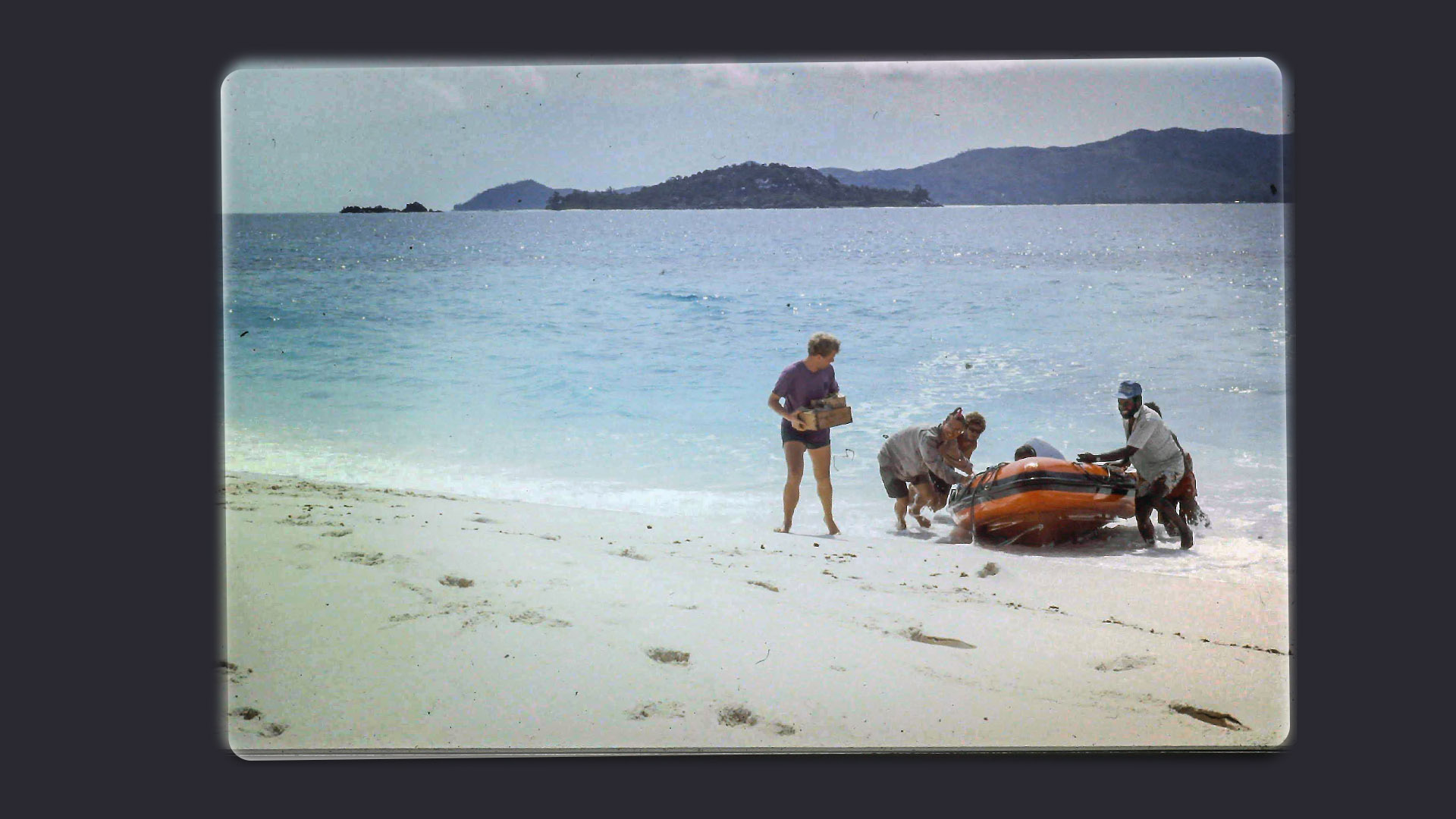

Komdeur did his work under challenging circumstances: there was no electricity, no readily potable water, and no beds. He and his wife had to catch and kill all their food; they ate mostly shark and fish. Either that, or they had to take their rubber boat and go several kilometres to the next island over to get supplies.

Occasionally, some tourists would stop by, but other than that, the couple lived alone on the island, surrounded by birds, giant tortoises, lizards, and crabs. ‘It was fantastic. Primitive, sure. We’d work like dogs, seven days a week. But sometimes... Sometimes it did get a bit lonely.’

It wasn’t without its risks either, because contacting the outside world was hard. ‘My wife got injured once and it got infected because we weren’t getting enough vitamins. Fortunately, a visiting tourist happened to be a doctor. He operated on her right on the island, without anaesthesia’, says Komdeur. ‘We later realised she could’ve just as easily died.’

Helpers

In spite of all the hardship, Komdeur still managed to discover a laundry list of interesting warbler characteristics. It turned out that Seychelles warbler breeding couples made use of helpers: birds that didn’t brood themselves, instead helping raise the chicks of others. We now know that they do this because there simply isn’t enough room on the island for every bird to have its own territory. By helping others, they ensure that their genes are still passed on, since they share them with their family.

If they don’t have a enough food they have a son who’ll leave the nest

No one knows why the warblers didn’t just fly to a different island to establish a territory there. Perhaps it’s because in the past, warblers were in fact spread out across the island, and the Cousin birds figured there wasn’t any room for them, even though the other birds had long since died out.

Komdeur also found out that female birds can choose whether to have a son or a daughter. This is useful, because only the female birds volunteer to be helpers, which means the brooding pairs were able to choose whether they wanted a helper or not.

‘If there’s enough food to go around, they’ll have a daughter so she can help them raise any future chicks without the parents sacrificing any food’, Komdeur explains. ‘But if they don’t have enough food, they’ll have a son who’ll eventually leave the nest to start a new family elsewhere.’

Moving brooding pairs

In 1988, Komdeur was granted permission to not only study the warblers, but also to fight for their preservation. He was allowed to move several brooding pairs to the neighbouring islands of Aride and Cousine. This led to various empty territories on Cousin.

‘This allowed me to look at something else I’d been wondering’, Komdeur says. ‘How do birds decide whether to start brooding or become a helper?’

It’s a unique opportunity to study an enclosed population

This, too, turned out to be related to the amount of food available in any given territory. It’s smarter for birds to help out their parents in a territory that has a lot of food than to go off on their own to brood in one without much food, where there’s no guarantee your chicks will have enough to eat.

In the meantime, the mission to save the Seychelles warbler has been a moderate success; the birds are no longer confined to Cousin. They’re now flourishing on five of the islands in the Seychelles. On top of that, the birds have gone from ‘endangered’ to ‘vulnerable’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Laboratory

These days, Cousin even has a permanent island warden and a modern research complex. ‘We have our own laboratory, solar panels, a fridge and freezers for tissue samples, all of that.’ There are at least ten researchers on the island at any given time, studying the warblers and other natural things on the island. Most researchers work at the UG. ‘It’s a unique opportunity for researchers to study an enclosed population’, says Komdeur. Plus, Komdeur has a lot of long-term data from those thirty-eight years.

He is still working hard on the project. He recently applied for a 2.5 million euro ERC grant to continue the study into the Seychelles warbler. The question he’s focusing on this time is how the bird is dealing with climate change.

He would love to be able to start a new study, says Komdeur. ‘The local people always welcome me with open arms, and I love them, as well. Going back there is like a warm blanket. It feels like home.’