Christiaan Triebert is Alumnus of the Year

‘I was never a great student’

The city is buzzing with the news; everywhere you look, there are posters with his face on them. Christiaan is back! There are lectures, presentations, and workshops. Two years after finishing his bachelor’s degree in 2015, the young journalist was awarded the European Press Prize for his reconstruction of the coup in Turkey in 2016. He has worked for Bellingcat and Airwars. Currently, he has a position as visual investigations journalist at The New York Times.

Everyone wants a piece of Triebert while he’s here to be honoured as Alumnus of the Year during the opening of the academic year; they want to tell him something, ask him something, get him to do something. He doesn’t have much time: he still needs to prepare for a presentation, visit old colleagues, attend a dinner. He can’t find his bank card. But he talks to everyone. He answers their questions, nods affirmations, listens attentively, says a proper goodbye to everyone before moving on to the next obligation. So many people; so little time.

In a slight Frisian accent, he says he hasn’t eaten anything all day: ‘Do you mind if I pick up some food real quick?’ No problem; there’s a sandwich shop across from the UKrant offices, where Triebert had his got his start as a journalist. His first article, 10 questions about Groningen earthquakes, was designed to look like the type of articles Max Fisher wrote for The Washington Post and Vox. Back then, Fisher was a role model. Today, he is a colleague at The New York Times.

Fact checking

Triebert works for the Visuals Investigation Team. ‘Basically, all I do is fact check’, he says. But it’s a revolutionary new way of fact checking, and people pay through the nose to learn the method. In a documentary about Bellingcat, his former boss Eliot Higgins says Triebert has a special knack for what he does.

And now he’s the RUG’s Alumnus of the Year. He was awarded his prize on Monday. Triebert is honoured, but also a little uncomfortable. ‘I was never a very good student. There are so many people out there doing great things. I mean… who am I?’

Triebert studied international relations and organisation. He did a little writing in his free time, but his favourite pastime was photography. He would go up to people in the street, engage them in conversation, take their picture, and put it up on his Facebook page Humans of Groningen,

based on the well-known page Humans of New York. He documented encounters with people he would ‘otherwise have passed right by’. It’s typical Triebert: doggedly curious, he’ll always go for it.

Ukraine

So what’s his favourite UKrant article? ‘Oh, the Ukraine story, no doubt’, he says. He’s referring to two stories from February 2014. Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych turned his back on the EU, which led to protests breaking out across the country. Triebert wanted to be there. ‘They’re making history!’ he said. Copy editor Christien Boomsma sent him on assignment: ‘Talk to students and tell us their stories’.

Triebert went. In Ukraine, he spoke with leftist activists who were working with the extreme right in the country. He wrote about what it was like to be in the middle of the protesting masses when just a few streets away people were browsing expensive stores. And he loved every minute of it. ‘It was the first time I had been sent on an assignment like this. And they were paying me for it!’ He was curious, and he went for it.

‘I’m trying to eat less meat’, he says as he orders a goat cheese sub. He grew up vegetarian, but when he started hitchhiking – from Istanbul to Leeuwarden, from Groningen to Cape Town and the back east – he couldn’t maintain the diet. ‘You eat what people offer you’, he says with a shrug. ‘You don’t want to seem ungrateful.’ His hitchhiking ways are behind him now; he has a driver’s licence.

Why did all these lovely people hate others so much they went to war with them?

But hitchhiking taught him a lot – he even gave a TED talk about it in 2015. Every time a stranger picked him and his friends up, he saw it as an act of kindness – and those cumulative acts of kindness shaped his view of the world. He became even more interested in the nature of conflict. How is it that all these lovely people who were so kind and open to him could hate other people so much they would go to war?

He was curious, so he went for it – by continuing his studies. At the RUG, he studied philosophy and Middle Eastern and Globalisation studies. Then he borrowed money from his family to attend the prestigious King’s College in London, where he wrote a thesis for the Department of War Studies. The tuition was ‘exorbitant’ he says. On top of all that, living in London was impossibly expensive.

Nonetheless, he says he got a lot out of the classes taught by former journalist Ahron Bregman. ‘He had probably interviewed every single person in the Middle East’, says Triebert. Bregman was a gifted storyteller. ‘In the middle of a lecture he would suddenly segue into an anecdote about Netanyahu’s wife.’ Triebert also attended classes about warfare. They were ‘cool’, but ‘it was mainly people talking about their experiences rather than the theory behind the concepts’.

Even before he went to London, Triebert tried to get his career as a war correspondent off the ground. He travelled to Iraq to talk to the Peshmerga, who were battling IS. But once there, he started doubting himself. The area was practically crawling with journalists. ‘They were all ten times better than I was.’ What could he bring to the profession?

He felt he would be a detriment to the market as another green journalist willing to work for nothing. ‘Neither the Leeuwarder Courant nor the Dagblad van het Noorden ever paid me.’

No one was checking up on our air force’s bombardments

He found that whenever there was an air raid, he was often able to find out more about what had happened on the internet than by talking to people in the area. ‘No one was doing research that way. They just weren’t very interested.’ The Netherlands was doing a lot of bombardments, ‘but they never said which countries they were bombing. No one was checking up on what our air force was actually doing.’

He started investigating on his own; later, he would volunteer at several places, including Airwars and Bellingcat, where he was first introduced to the world of open-source intelligence (OSINT) pioneered by Eliot Higgins.

While he was still writing his thesis for King’s College (living in the much cheaper city of Kuala Lumpur), Triebert came across a Turkish revolutionary’s leaked WhatsApp conversation. He decided to investigate the contents, a project which eventually earned him the European Press Prize for innovation in journalism.

Geolocation

Today, Triebert’s speciality is geolocation: determining the origin stories of online videos and images. He inspects identifying markers in the background – like trees and buildings – and compares those to satellite images and other photos from sources like Google Maps. ‘We had complete freedom at Bellingcat. In that sense it’s kind of an anarchist organisation.’

But Bellingcat needed money, and other organisation wanted to know their method. So Triebert spent a year travelling across the world to teach journalists the Bellingcat method. He also collaborated with other open-source investigators to publish a daily puzzle on Twitter: @quiztime. Most of the time, they published a photo and asked people to pinpoint the location it had been taken.

The standards are higher now that he works at The New York Times, says Triebert. ‘We don’t publish just anything, and much more consideration goes into how we publish things.’ At Bellingcat, the parameters are looser: ‘People don’t always feel like reading a whole report.’ Another perk of his new job is that some of his research has to be done on location – more cool trips.

At only twenty-eight, and he’s already a well-respected journalist. So what will he go for next? ‘No clue’, he says. ‘But it’s not the destination that matters, it’s the journey. There is no single end goal.’

Open-source intelligence

Open-source intelligence is not hacking. It involves gathering information from public sources such as YouTube, social media, and Google Maps, as well as car registration data and Airbnb photos that are public. This information is used to identify facts about photos or videos, such as where it was taken, when it was taken, how it was taken, and who was in it.

If you want to try your hand at OSINT, try the websites below. We’ve provided you with some puzzles to solve. For more puzzles, follow @quiztime on Twitter.

Yandex; Wikimapia; Google Maps; Google Earth; ShadowCalculator

The quiz

1. The Groningen skyline in December. Where was this picture taken and at what time? Click on the picture to enlarge it.

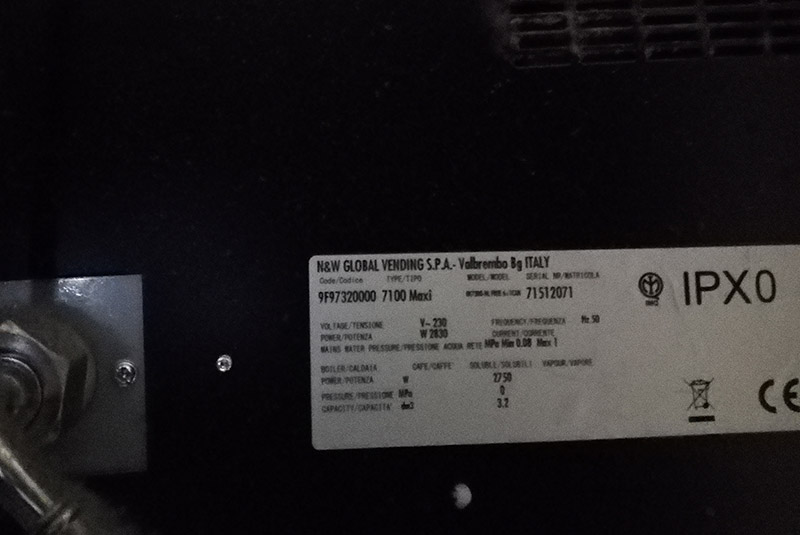

2. Who services this machine on a daily basis? And what’s the machine’s exact location? Click on the picture to enlarge it.

3. Which RUG professor does this image refer to? And where can they be found?

You can find the solutions here.