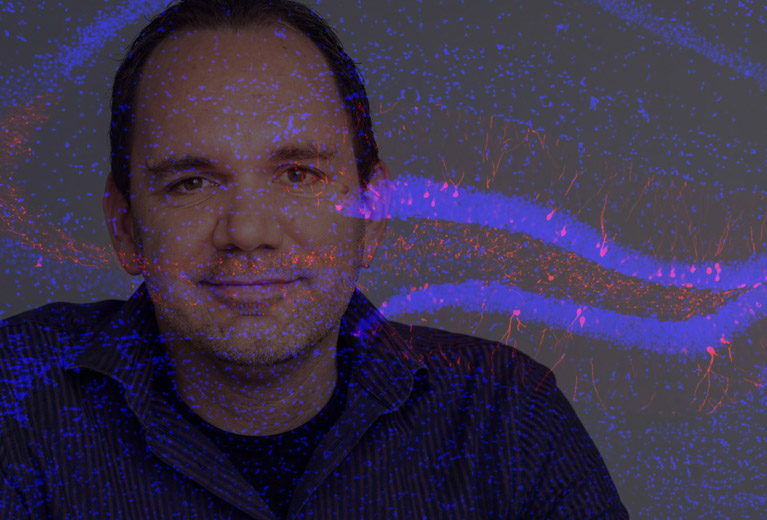

Robbert Havekes and his sleep-deprived mice

Finding lost memories

It’s a nice idea, the thought that your head is filled with memories. That everything you’ve ever experienced, read, or learned is stored somewhere in your brain. When you forget something, that knowledge isn’t lost forever; your brain is simply blocking the way to it. If you can unblock that, you can retrieve the memory.

Neuroscientist Robbert Havekes thinks this is possible. In fact, in an article published in Current Biology in December, he, his PhD student Youri Bolsius, and former Groningen post-doctoral candidate Pim Heckman showed that it can be done. He used sleep-deprived mice, the lost memory of a bottle, and an asthma drug that’s been on the market for decades.

Havekes has been studying the effects sleep deprivation has on the brain for years. It shouldn’t be news to anyone that sleep deprivation leads to a host of problems. It’s linked to burn-out, depression, excess weight, and heart problems, as well as memory loss.

‘Sleep is very important to the learning process’, Havekes explains. ‘Your brain continues to process and store information while you sleep.’

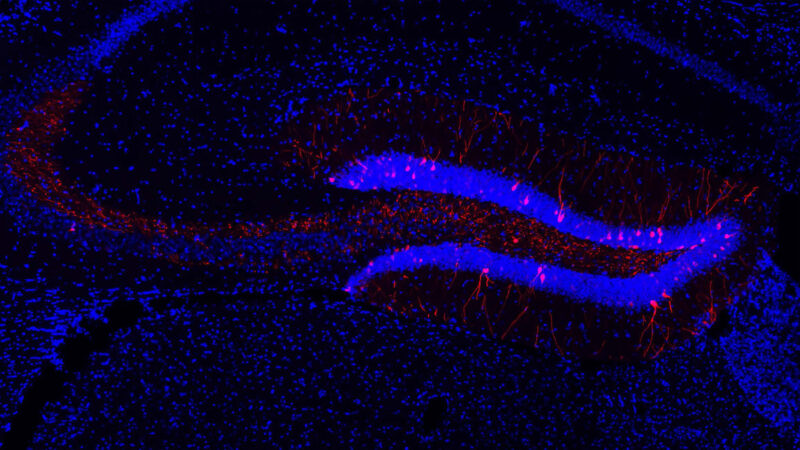

If you don’t sleep well or at all, that information isn’t stored properly in the hippocampus region of the brain. That becomes a problem if you have to take an exam the next day. ‘Even though you studied, you’ll have a hard time remembering the material.’

Forgetful mice

It’s this kind of memory loss that Havekes reproduced in the mice he uses for his research. He put them in a large container with several objects, such as a cube, a bottle, and a ball. Next, he split the animals into two groups. One group was kept awake for five or six hours, while the other group was allowed to sleep.

Your brain continues to process information while you sleep

The next day, he put the animal back into the same container. It turned out that the group that had got a good night’s sleep was able to remember the location of the objections. But the group that had been deprived of sleep after their training was not. ‘I could tell by the way they explored the objects’, Haveke says. ‘When an object had been moved, they would sniff at it more, put their front legs on it.’

To be fair, this behaviour wasn’t exactly news. In fact, Havekes and his team discovered back in 2016 that the brain cells of these forgetful mice, where specific memories are stored, show fewer synaptic connections. He also discovered that you can make brain cells ‘resistant’ to the effects of sleep deprivation by using a specific asthma drug called roflumilast.

‘This drug impacts the way specific proteins work’, he says. ‘But they work differently in the lungs than they do in the brain. In the brain, they’re partially responsible for breaking down synaptic connections.’

Blue light

However, their current research focused not on preventing memory loss, but on recovering lost memories. Then there was that other, even more fundamental question: is lost knowledge gone forever, like some scientists think? Or is it just hiding? This particular idea has been gaining strength over the past few years, mainly because of Alzheimer’s research.

To find out whether it could be done, Havekes applied two different methods to his forgetful mice. First, he used optogenetics. He marked specific cells in the hippocampus where the mice had stored their memory of the bottle. Just before the mice were returned to their containers, he shined a blue light on that particular area.

‘It worked!’ he says. ‘Whenever we did that five minutes before the animals went into the container, the memory suddenly resurfaced. That means the information wasn’t lost, it was hidden in the brain somewhere.’

However, this blue light method is complex and can’t be applied to human beings. Havekes repeated the experiment using roflumilast. He was once again successful in making the mice remember the location of the objects.

A mouse gets his first training in the exercise box. When he later forgets the objects due to lack of sleep, he will sniff as much on a second time as he did the first time. Video Lab Havekes.

Quickly forgotten

Unfortunately, the memory was only reactivated for a short time. The next day, the animals had forgotten everything all over again.

Havekes had a feeling he could do something about this and decided to do one last round of experiments. This time, he combined the light method and the roflumilast. This led to spectacular results: not only did the mice pass the test with flying colours, they also retained the memory for at least two days. ‘That memory track in the brain was permanently accessible again.’

We might be able to alleviate the effects of Alzheimer’s in an early stage

This is good news, says Havekes, because many people are struggling with memory problems, such as elderly people or Alzheimer’s patients in the early stages of the disease. ‘In its later stages, the disease damages areas like the hippocampus too severely. But we might be able to alleviate the effects of it in an early stage.’

Because, he says, we now know that it’s possible. ‘Since roflumilast is already available on the Dutch market and doesn’t present any nasty side effects when the right dosage is used, making the leap to studying this on people is much easier.’

Subliminal

We won’t know that it really works until we study it, he emphasises. ‘But mice brain cells don’t differ that much from human ones.’

Of course, you can’t open up people’s brains and shine light on them to boost the effect of the roflumilast, but there are other possible methods. ‘Such as subliminal influencing: you could ask someone to learn a list of words and then quickly flash it on a screen right before the start of the experiment. People won’t notice it consciously, but their brains will process it.’

Do we really want to recover memories of trauma and grief?

He expects Pim Heckman, who now works at the University of Maastricht, will continue the research. Havekes himself is less interested in how to apply his research to people, and more in fundamental questions. This study has engendered a host of new ones.

Bad things

‘The next step is to figure out whether this only affects spatial learning or whether it also applies to other types of declarative memory; facts’, says Havekes. One of his PhD students will soon be starting an experiment in which mice are tasked with recognising individuals.

He also wants to see if there are any other methods to recover lost memories. There are more proteins involved in memory than just the one that’s impacted by roflumilast, which means there are potentially other drugs he can use.

But, he emphasises, you shouldn’t want to recover every single memory ever. ‘The brain’s storage capacity is vast. You can tell when you’re looking at old photos and you start remembering things you thought you’d forgotten. But there are also plenty of bad things we’ve forgotten, such as trauma and grief. Do we really want to recover those memories, too? Perhaps we could develop a similar strategy to permanently erase those bad memories instead.’