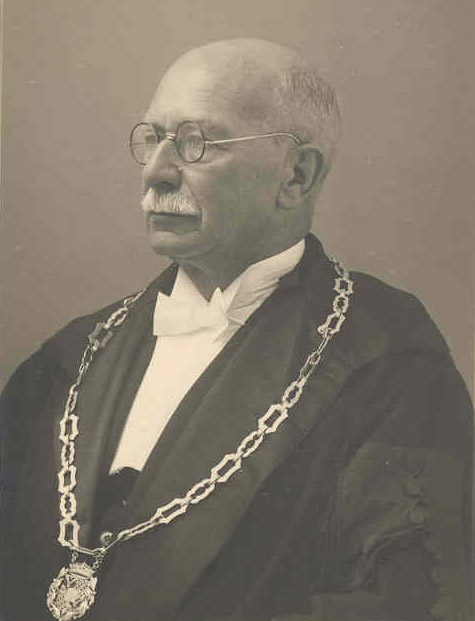

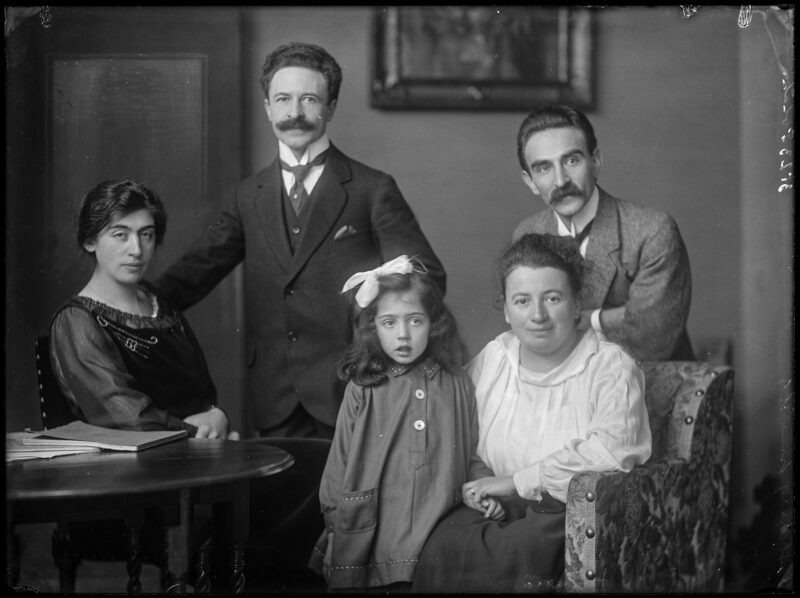

J.M.N. Kapteyn and Leo Polak

The Groningen rector who betrayed a brilliant philosopher

Perhaps he’d simply been a bit inept when the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD) was questioning him at the Scholtenshuis in Groningen. Perhaps he hadn’t meant to badmouth the philosopher, and perhaps the latter’s subsequent death was simply a coincidence.

At least, that’s what the pro-German UG rector magnificus Johannes Marie Neele Kapteyn (not to be confused with professor of astronomy and theoretical mechanics Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn (1851 – 1922), after whom the Kapteyn Institute is named) insisted once the Second World War was over, when he was made to answer for the death of the Jewish philosopher and lawyer. Polak had been arrested on February 15, 1941, and imprisoned at the Scholtenshuis, the infamous SD headquarters. He was the first Jewish person to be deported, and he was murdered on December 8, 1941, in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

This all took place after the Germans had got hold of a letter that Polak had written to the arts and philosophy faculties. In this letter, he lamented how he had not only been suspended from his work as a professor but had also been banned from faculty meetings. ‘As far as I know’, Polak wrote, ‘the University of Groningen is the only university to add this injustice to the injustice already done by the enemy.’

But this letter was meant for faculty eyes only. The only reason the Germans even knew what it said was because Kapteyn had shown it to the SD. ‘By accident’, Kapteyn argued. He’d just happened to have the letter on him when the SD summoned him to the Scholtenshuis in late 1940.

Short sentence

He later said he’d actually been trying to defend Polak, and he had ‘unwittingly’ taken the letter from his portfolio. SD officer Dr. Scholz asked him about it, ‘taking it from my hands in spite of my protests’.

Kapteyn was irked that Polak kept criticising the university

Besides, said Kapteyn, things ‘weren’t as bad’ in late 1940. He figured people would ‘excuse’ Polak for ‘such a trifle’.

This constituted Kapteyn’s successful defence when he was prosecuted in 1948 for his NSB membership, his close ties to the SS, and his betrayal of Leo Polak. The court decided there was no ‘proven causality’ between Polak’s arrest and Kapteyn handing the letter to the SD. Kapteyn made off with a short sentence. Since he’d already spent a year in an internment camp, he didn’t have to go to prison.

Two letters

However, people’s views on the rector have been changing over the past few years. Research by UG historian Stefan van der Poel and former NIOD researcher Gerrold van der Stroom, among others, has shown that the SD didn’t have one, but two letters. Kapteyn had taken at least one of these with him under the loud protestations of the faculty secretary.

On top of that, he had been to the SD headquarters more than once. So how accidental were these incidents?

Kapteyn is kind of a controversial figure in the UG’s history. It all started in 1940, when he was suddenly appointed rector magnificus. While he had in fact been nominated for the job, he was only third on the list. But the university appointed him after being pressured by the occupiers, since the Germanic scholar and rune expert had German sympathies. ‘100 percent Dutch, who fully understood Germany and the German people because of his background’, he would later write about himself.

The other professors at the university were furious. They either avoided the celebrations that followed his appointment or refused to congratulate Kapteyn. ‘Pretended he wasn’t there in the faculty room’, Polak later wrote in his diary.

Pro-German university

But Kapteyn had the support of the Germans, and the professors who’d said his appointment was an ‘insolence’ were soon described as ‘deutschfeindlig’ in the SD’s reports to the home front. Public protest quickly died out.

You don’t end up at the SD with a letter in your pocket if you don’t plan to hand it over

Groningen quickly became known as a pro-German university. Kapteyn encouraged professors to sign the Aryan certificate, even though 80 percent of people in Groningen were against this. When a numerus fixus for Jewish students was introduced, he implemented it without question, and he said nothing when Jewish professors were relieved of their duties.

In November, Leo Polak was told he was no longer welcome at the university. In his diary, he wrote that Kapteyn and the secretary wanted ‘me to leave quietly […] to prevent the university from closing’. ‘Colleagues were discouraged from interacting with him’, says Van der Poel.

But Polak decided to make a fuss. In December he wrote the faculty to ask why they’d stopped inviting him to PhD ceremonies and exams. He realised he’d been relieved of his duties, but he felt the faculty was acting ‘as though I wasn’t a Groningen professor at all’.

No action

Kapteyn must have been vexed. ‘He was extraordinarily irked that Polak kept criticising the Groningen university’, says Van der Poel.

So while Polak didn’t receive an answer, his letter did end up at the Groningen branch of the SD. Van der Poel found out a few years ago that the SD had had the letter translated and published in their weekly report Meldungen aus der Niederlanden on January 7. This must have been the letter that Kapteyn had ‘accidentally’ taken with him and which had ‘accidentally’ been taken from him.

But the SD took no action just yet. While they did note in their publication that Polak was ‘einer der deutschfeindlichsten Elemente der Groninger Universität’, they left him alone.

Five weeks later, the faculty answered Polak after all, saying that being relieved of his duties meant he couldn’t do any work for the university. That’s when a furious Polak wrote that Groningen was the only university to ‘add this injustice to the enemy’s injustice’.

This letter was mentioned in the February 11 edition of Meldungen. This time, the Germans did decide to intervene: ‘Seine Festnahme ist veranlasst.’

Three days

Kapteyn’s ineptitude would have been perfectly understandable if it had only happened one time. He claimed he had the first letter with him because he wanted to discuss it in a Senate meeting, and these meetings were often months apart. But it’s also clear that faculty secretary Enk didn’t want to give the letter to Kapteyn. He later said that Kapteyn had practically ripped the letter from his hands and refused to return it.

He absolutely knew what would happen

Moreover, Polak’s second letter found its way to the Scholtenshuis in just three days. ‘Kapteyn acted incredibly quickly’, Van der Stroom writes.

And another thing: Kapteyn never felt the need to warn Polak that the Germans had interrogated him. According to him, the philosopher was advertising his anti-German sentiments anyway. He must have known he was being watched.

When Polak had been captured, Kapteyn took no action. ‘The disappearance of the Jewish intellect was simply the inevitable consequence of the new order’, wrote historian Klaas van Berkel.

Rewarded

The Germans were big fans of Kapteyn. Even outside the ‘Polak matter’, says Van der Stroom, he was likely in regular contact with the SD. According to them, he was ‘der deutsche Sache ehrlich verbunden’.

Van der Stroom even thinks Kapteyn was rewarded for his betrayal. Immediately after Polak’s arrest, letters were sent to and from the SD about funding a book on Kapteyn’s rune research. Polak must have told them about this research. ‘The SD undoubtedly wanted to keep Kapteyn as an informant and sought to charm him even further’, he writes.

Not that such a book was ever published. German researchers felt the rune expert’s conclusions were a bit fantastical sometimes, and Kapteyn had to make do with the honorary title of Untersturmführer.

Van der Poel isn’t certain he was ever actually rewarded. He does know that Kapteyn’s post-war defence is nonsense. ‘You don’t end up at the SD with a letter in your pocket if you don’t plan to hand it over’, he says.

While Kapteyn always insisted he was ‘an intellectual’ and ‘naive’, that kind of reasoning just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. ‘He absolutely knew what would happen’, says Van der Poel. ‘Jews had been coming to the Netherlands with stories about concentration camps since the thirties. His colleague, Polak-Daniëls, had committed suicide. Kapteyn knew that Polak’s arrest meant he would be sent on to a camp. And he knew that it was more than likely that he would die there.’

Sources for this article:

Gerrold van der Stroom, J.M.N. Kapteyn en Leo Polak, en Ludwig Erich Smitt. Dubbelvoudig verraad en overmoed aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen tijdens de Duitse bezetting (1940-1942) (Amsterdam 2018)

‘“De zaken moeten nu eenmaal loopen”. Kapteyn als rector van de Groningse universiteit (1940-1942)’, in Groniek. Historisch Tijdschrift 32 (1999) 311-319

Klaas van Berkel, Academische Illusies. De Groningse universiteit in een tijd van crisis, bezetting en herstel 1930-1950 (Amsterdam 2005)

Klaas van Berkel en Stefan van der Poel (ed), Nieuw licht op Leo Polak (1880-1941). Filosoof van het vrije denken (Hilversum 2016)