Scamming internationals

Hunting the housing mafia

UK journalists Leonie en Nina go undercover and get in touch with people offering non-existent apartments in Groningen. The swindlers hide behind names like Sandy He and Martinez Herben. The UK locates the swindlers, but the whole thing turns out to be more complicated than they thought.

Previously

Fake IDs, excuses, lies, repeated requests for money transfers. In the first part, we found that Sandy He and Martinez Herben are using the same method to con students looking for a room or apartment all over the world. In part 1, we went to an apartment at Het Hout which Martinez Herben was offering for rent for an upfront payment of 1,200 euros. It quickly turned out to be a fake apartment. Martinez Herben is not punished, however. He can continue his scamming ways.

The conclusion

Shortly after the failed acquisition of Het Hout 12, a new advertisement pops up in one of the Facebook groups offering rooms and apartments for rent. Cruz Perez Alvaro is offering a house at the Reitdiephaven (number 225). We tell him we are interested.

He then refers us to the owner and provides us with an email address. At this point, we are no longer surprised to find out this is Martinez Johberg Herben, the same conman who offered up Het Hout. He (Alvaro/Herben) gives us the same line as before: he has been living in England for a month, he will be staying there four years for work, and the apartment at the Reitdiephaven can be rented for a shorter or longer time.

In the meantime, we spoke to the Groningen housing corporation Lefier about Het Hout 12, who ultimately rents the apartment out. They say that they are not aware of any wrongdoing in connection to the apartment. ‘If we suspect anything illegal is going on, we involve the police.’

‘But we have the “offer” on Facebook, a rental contract for Het Hout 12, email exchanges, and more’, we reply. ‘How much evidence do you need?’

Lefier does not seem to believe in the idea that prevention is better than cure, at least based on their response: ‘Unless someone comes to us and says: “Hey, I rented this”, and the apartment is already inhabited by someone else, we will not take action.’

Trysha McKay

But back to Alvaro/Herben and Reitdiephaven. We decide to take him up on it once again. This time Nina pretends to be Trysha McKay from Bulgaria, looking for a place to live in Groningen from Budapest. After several exchanges via email, Martinez Herben sends us pictures of the apartment at the Reitdiephaven.

They are the exact same pictures he sent us of Het Hout: the slightly kitschy living room, the luxurious bathroom, and the same small kitchen that does not even remotely match the rest of the apartment. It shows how brazen this particular conman truly is. Once again, he wants 1,200 euros transferred to his account before we can do business.

<DIALOOG TRYSHA MARTINEZ>

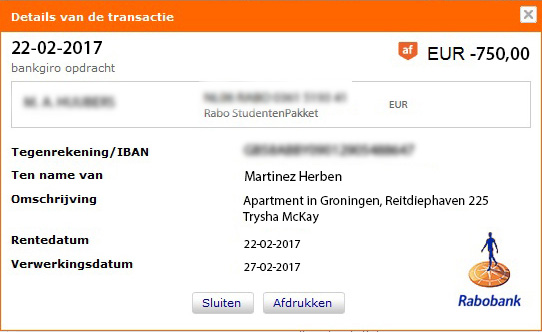

We pretend to pay the 750 euros and make a screenshot the ‘bank transfer’ which we email to Martinez Herben.

<SCREENSHOT TRANSACTIE>

Martinez Herben is pleased and seems to take the bait when he sees the bank transfer. He says he will come to Groningen to hand over the keys. On an overcast Tuesday evening, we cycle over to Reitdiephaven 225, eager to finally meet this man. But we wait, and we wait. The bottle of champagne we brought to celebrate getting the keys never makes it out of the bag: Martinez Herben does not show up.

Something is off

But he does contact us one more time. Despite the transfer we sent him, he has not received the 750 euros yet, he writes angrily in an email. We say that something must have gone wrong, but Martinez Herben seems to sense that something is off. He breaks off all contact.

We are no closer to unmasking this conman. We pool our resources: the entire UK team gets together for a ‘hack-a-thon’ in the hopes that we will be able to unearth this Martinez Herben somewhere. After hours of investigation, we strike gold by trying different variations of the name. We find our Martinez Herben, although his name turns out to be Martin.

The passport that the conman has sent us turns out to have been photoshopped. Its actual owner is named Martin Johannes rather than Martinez Johberg. But the passport has indeed been issued by the Chinese embassy. Martin Herben lives in The Hague and works at a high school, but up until a few years ago, he worked in China at an international educational institute.

Editing a copy of a passport is simple and the end result looks very much like the real thing.

We track down his phone number and talk to the real Martin Herben. It turns out he is a victim of identity theft, and not for the first time. He tells us that a year ago a bailiff suddenly knocked on his door. He was sent by an Argentinian student who demanded the money he supposedly took from her as rent and a security deposit for a non-existent apartment. The ‘real’ Martin Herben pleaded innocent.

Martinez Herben has been misusing Martin Herben’s identity for longer to swindle students all over the world. The real Herben has no idea how internet swindlers got ahold of his passport. It probably happened when he was living and working in China. ‘In China, I looked for living space through agencies and I stayed in hotels. They always make copies of passports’, he says. ‘Everyone has a copy of your passport these days.’

Report

Martin Herben reports the identity theft to the police station in the Torenstraat in The Hague. They tell him the police will not be able to do much for him. ‘That seemed strange to me. There’s not much I can do myself, either. All the scammers have to do is alter the data on my passport and they can just keep using it.’

In the meantime, we go looking for that other swindler: Sandy He, the woman who took money from students all over Europe and whose passport was used in Groningen to cheat the Hungarian students Ibolya Vörösváry and Alexandra Ruisz out of hundreds of euros. After a long search, we find Sandy He in Calgary, Canada.

Just like Martin Herben, the real Sandy He is the victim of identity theft. She says that during her internship in Hong Kong in the autumn of 2015, she went looking for living space in all manner of ways before she was due to leave. But she had no luck. Finally, she found an advertisement for a lovely apartment in a great location on Facebook.

It turns out to be too good to be true. She emails a copy of her passport to the swindlers. That passport is later used in dozens of places around the world to take money from others. At first, the real Sandy He is hesitant to tell us her story, but eventually, we talk to her over Skype.

‘I feel so terribly guilty. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about it’, she tells us from Calgary. ‘I know people are calling me a swindler.’ The identity theft has greatly impacted the real Sandy He’s life. She is anxious and barely travels by plane, afraid she will get arrested. She uses a different name on all her social media accounts, and she has told her employer about the situation. ‘But I’m afraid it’ll come back to haunt me every time I look for a job.’

Money trail

We have one final bread crumb to follow: the money. This is easier said than done. Marie Dammen, the Belgian student who fell prey to the fake Sandy He (see part 1), transferred money to a bank account in Malta in the autumn of 2015. That account was in the name of a Mark Bugeja.

We track him down. Well, actually, we find dozens of him: there are quite a few Mark Bugejas living on Malta, where the name is as common as John Smith. None of the men can be directly linked to our case. After several fruitless attempts to get the Maltese bank to tell us the real name belonging to the bank account number, this trail ends, too.

But there is still the money trail left by Hungarian students Vörösváry and Ruisz, who transferred hundreds of euros for the non-existent apartment at the Nieuweweg 26 in Groningen to an SNS bank account belonging to a Violet Mary K. who lives in Amsterdam. Her address was included in the email as well.

Transferring money

When you transfer money to a bank account, you always have to enter the recipient’s name. But Dutch banks do not actually check if that combination of name and bank account number is correct. The Netherlands is currently working on stricter legislation to tackle this. In the future, if you enter the wrong name when transferring money to a Dutch bank account, your money is returned. For foreign bank accounts, whether the money actually ends up with the addressee is still unclear (for now).

We are unable to dig up much about Violet Mary K. online, but we do find a profile on Russia’s answer to Facebook, VKontakte. Could there really be a link to Russia, as Marie Damman’s lawyer suggested earlier?

Weird story

The profile on VKontakte contains two photos of Violet Mary. They appear to have been taken in the same house. On a Friday afternoon, we ring the doorbell at the address provided. Mary Violet K. turns out to be a middle-aged woman. We immediately recognise her from the pictures on VKontakte. Her story is a bit weird: she feigns innocence, saying the bank account number is not hers. But when we ask to see her bank card to compare the numbers, she refuses. She claims her name is being used to con people.

Is she a money mule, in cahoots with the swindlers? Or is she just another one of the real swindlers’ victims?

Responsibility

The university is attracting an ever increasing number of foreign students, but does not offer them much in the way of information about how to rent a room and what to look out for. Both police spokesperson Robbert-Jan Valkema and legal advisor Denise Zonnebeld at Frently feel that the RUG should focus more on prevention. ‘The tenants themselves have the most responsibility, obviously. But the RUG and the Hanze University of Applied Sciences should provide students who enrol from abroad with an information packet. Then they’ll know exactly what to expect’, according to Zonnebeld.

Even the police have trouble figuring out who is behind it all, says police spokesperson Ramona Venema after our questions about Vörösváry and Ruisz’ report. ‘In cases like these, we often find that people are using foreign bank account numbers supplied by money mules. These people make their bank account available in return for a fee. It often involves vulnerable people with no permanent address who need a little extra money. We often don’t have enough leads to actually come up with a suspect.’

Lacking

That is strange, says Denise Zonnebeld, legal adviser at Frently, an organisation that helps students with rental problems. She calls the response from the Groningen police ‘lacking’. ‘We can’t expect them to solve the problem on their own, but they are obligated to take down reports. That way they can create files. It happens way too often that the police send victims away, saying they can’t help them.’

Zonnebeld adds, ‘Students who have been swindled in Groningen often report the crime in the city they come from, which makes it unclear how many foreign students are being conned. That is why I always tell them to report it. And there should also be a unit where all the reports concerning this type of fraud are collected, maybe even an international unit. If the police were to track IP addresses and follow the money through the bank accounts, they could definitely help.’

Despite the false start, Vörösváry and Ruisz are feeling perfectly at home. However, they are still angry. Not even necessarily with the swindlers; they know they will never get the money back. But it is the police’s reaction that does not sit well with them. Or rather, the lack of reaction. ‘To be honest, we expected them to go after the swindler. But since we reported the crime, we haven’t heard back from them at all. We’re very disappointed.’

What happened to the report?

This is where our own search ends. The police can trace people based on their bank accounts, IP addresses and email exchanges. We cannot. So the question remains: what happened to the Hungarian students’ report?

That remains unclear. Ramona Venema of the Groningen police: ‘That report is part of an ongoing investigation. We’ve handed the case over to the Amsterdam police.’

But when we ask the police in Amsterdam, they are no help. They say the case is not known to them. Either the files were never handed over, ended up on the bottom of a pile somewhere or were lost.

The Public Prosecutor (OM) for the Northern Netherlands says that ‘it is really disappointing that nothing was done with the reports and that the police are treating reports like this, because we can absolutely act on these reports. They can be used to build a case and then the OM can investigate it further.’

For now, the capital police are still trying to figure out exactly where the report wound up.

The following people contributed to this project: Nicole Aldershof, Lena van Dijk, Simone Harmsen, Nina Jansen, Peter Keizer, René Lapoutre, Koen Marée, Rob Siebelink, Leonie Sinnema, Sjef Weller, Traci White and Nina Yakimova

What should you do when your identity gets stolen?

If you think your personal information has been stolen, but you are not sure if it has been used in a crime, notify the police. You can make an official report later.

But if something criminal has happened, report it. The way you report it depends on the seriousness of the offence. In the case of identity theft, you need to make an appointment at the police station. Bring as much evidence as you can: bank account numbers, phone numbers, and IP addresses are especially useful to the police. Without a report, the police cannot investigate, and you will be unable to recoup the damages from your insurance or the perpetrator.

Did you send someone your ID and do you think it is being misused? Request a new ID from the city. Each document has its own unique number. Should someone make use of your identity in the future, you will be able to prove it was not you.

Report the identity theft to CMI. They can help.

Be careful when sharing your identity documents. Check what kind of data organisations are allowed to ask for online. The Dutch Data Protection Authority’s website contains more information about who is allowed to ask for a copy of your ID.

You can use the app KopieID to make a safe copy of your ID.