Movember: sense and nonsense

Hairy men everywhere

Chris Smit’s beard

Associate professor of biology Chris Smit has had his impressive beard for five years now. ‘I have to compensate for my bald head’, he jokes. ‘Actually, my son has never seen me without it.’

Once upon a time, his beard was even longer, but it was always getting in his way. ‘It was difficult to handle’, he says.

He trims his current beard whenever his wife complains about it. Usually he does it himself, but every now and again he indulges in a visit to barbershop De Zware Raaf. On rare occasions he may even use beard oil. ‘It smells great, but I’m actually not into that stuff so I don’t use it very often.’

tekst prostaatonderzoek 1

Prostate research #1

Prostate cancer? Don’t panic

Igle Jan de Jong, oncological urologist at the RUG, does not have a moustache. And he certainly refuses to grow one during Movember, the month when men grow their moustaches to raise awareness and money for prostate cancer and research into the disease. ‘I will never grow facial hair’, he says, determined.

Bart Vanhauten, radiotherapist at the UMCG, does have a moustache, as well as a beard. He grew them during his last summer vacation. But he refuses to shave them at the end of Movember.

Both men’s professional careers revolve around prostate cancer. One focuses on research and treatment, while the other irradiates it. But they both agree: ‘prostate cancer is not that big a deal.’

Excess of treatment

This might seem like a curiously cold stance. But the numbers support their ambivalence. Because while 80,000 Dutch men are currently living with prostate cancer and 11,000 new men are diagnosed each year, the disease develops extremely slowly and is responsible for only 3.5 percent of all 72,000 cancer deaths in men.

Prostate cancer will happen to any man who lives long enough, says Vanhauten. The question is, how big a deal is it? ‘Most men die with prostate cancer, but not of prostate cancer’, he explains.

‘99 percent of people who get it live for another fifteen years or more’, De Jong adds. ‘You will always lose that remaining one percent, whether you actively treat them or not. Prostate cancer is not the biggest threat to men’s lives.’ But an excess of diagnosis and treatment is a problem.

Kevin Kelly’s beard

Student of artificial intelligence Kevin Kelly has a wonderful red beard and gets compliments all the time. He and his beard have been inseparable for nearly a year. ‘Last Christmas I decided to just let it grow’, he says.

It doesn’t take much to keep it neat and tidy. ‘Mostly I just keep it kind of trimmed and make sure it doesn’t get too wild.’

He doesn’t have strong feelings about the Movember movement. ‘But I’m aware of it. Friends of mine have participated’, he says. But there is little chance he would shave his beard and moustache off at the end of November, even for charity.

tekst prostaatonderzoek 2

Prostate research #2

Surely we have to do something?

Every day, people show up at their GP to ask for a PSA test, the standard method for detecting prostate cancer. The problem is that this popular test is ‘sub-optimal’, Vanhauten says, with evident contempt. In other words, it doesn’t do what it’s supposed to.

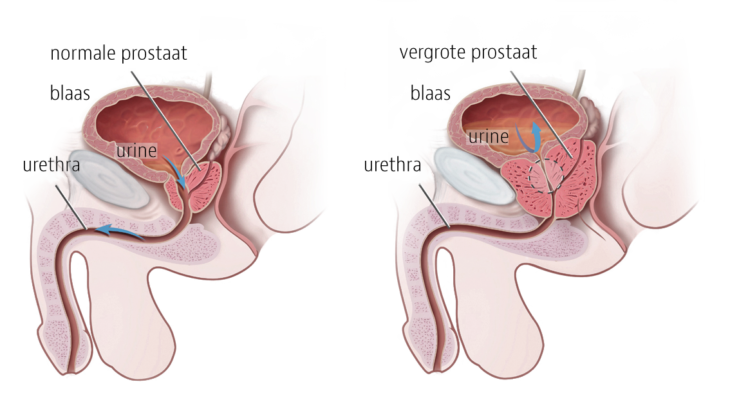

‘PSA is a protein made by the prostate gland’, De Jong explains. ‘Most of the protein is ejected with seminal fluid, but some of it always ends up in the blood. But when the prostate is enlarged or suffering from some other issue, a greater amount of proteins end up in the blood.’

The problem is that an increased PSA level isn’t necessarily indicative of anything. A high reading can be completely normal, while some people with prostate cancer have a low reading. Vanhauten: ‘The only real use PSA has is as a marker for how the disease is progressing. If someone’s PSA level goes up after surgery, we know that the disease is active again.’

But all these men with higher PSA values end up at a specialist who examines them and often finds the suspected prostate cancer. Off they go for treatment.

Impotence

Experts know that prostate cancer is very treatable. But the side effects of that treatment can be pretty nasty. Both surgery and radiation can lead to impotence and incontinence. ‘Radiation also causes scar tissue to form on your bowels, which causes men to feel as though they can’t hold in their poop.’ None of this sounds particularly lovely.

And in many cases, treatment is not even necessary. The PSA test may have uncovered a cancer that never would have caused any trouble. But that’s very difficult to explain to patients: ‘It’s impossible!’ says Vanhauten.

‘When young men show up, treatment is the obvious option’ he says. ‘For them, the risk outweighs the side effects. But a 78-year-old man who’s maybe had two heart attacks already and whose cancer isn’t very aggressive?’ Someone like that may never even suffer the consequences of prostate cancer. ‘But they’re so determined to get treatment it’s impossible to convince them otherwise.’

Kyriakos Pilidis’s beard

Bachelor student of physics Kyriakos Pilidis has had his beard for a year and a half. Growing it was a ‘crazy six month process’.

He doesn’t often get comments, he states. At least, not until Santa tries to upstage him at Christmas time. ‘People then tag me saying, “you should have that beard dominance!”’

tekst prostaatonderzoek 3

Prostate research #3

Do we need better screening?

Of course, that doesn’t diminish the fact that some men do die from metastasised prostate cancer. These men are usually a little younger, between forty-five to fifty years old. Their cancer is usually more aggressive, and they have a lot of life left to live. Men often wonder why they aren’t asked to participate in a population study, such as the biennial breast cancer study among women.

The simple reason? There is currently no proper testing method. ‘They did a big study into screening using PSA measurements’, De Jong says. ‘It showed that mortality rate went from 0.8 to 0.5 after fourteen years. A thirty-percent risk reduction might seem like a lot, but we’re talking very small numbers here.’

‘It’s like putting a fire station on every street corner and concluding that the chances of your house burning down are minimal’, says Vanhauten. ‘Is that really worth all the money it would cost?’

Holy Grail

The real win is being able to tell the difference between the aggressive, dangerous cancers and the benign ones. Recently, a urine test was developed that is capable of ‘skipping’ the dormant forms of cancer, says De Jong. The only problem is that this test costs approximately three hundred euros, while the PSA test costs only ten.

The data from the large Rotterdam study did suggest a possible alternative: an app that can estimate risk. It is currently being used by urologists. The cheap app appears to work just as well as the urine test. But it can only be used after a patient has taken the PSA test.

And so it’s not quite the Holy Grail just yet. De Jong: ‘Most urologists insist that the disease simply isn’t high-risk enough to warrant investing that much money.’

Justin Richardson’s beard

Nobody at the university knows PhD student Justin Richardson without his beard. He’s had it for eight years already. And he’ll never shave it off. Well… ‘Maybe when it gets too grey. That may be point that I decide to take it off.’

He trims his beard whenever it gets messy, he says. ‘And when my girlfriend says I have to.’

He has good advice for other men with beards: when you trim, take your time. ‘Otherwise, you risk taking whole chunks out.’

tekst prostaatonderzoek 4

Prostate research #4

Illusion of control

So we’re talking about a type of cancer with a high chance of survival and which often doesn’t even lead to symptoms. Yet every November men grow their moustaches. Why?

Vanhauten sighs. ‘I mean, we also have the Ice Bucket challenge, people swimming in the canals, biking up the Alpe d’Huez… although I’d rather bike down it. It’s an emotional thing.’

Events like these are often organised by patient organisations and others who have been confronted with cancer who feel the need to do something. ‘Maybe it’s just an element of this modern age’, he says. ‘We want to be able to influence everything, make it tangible. We want control, or at least the illusion of control.’

Alpe d’Huez

He knows these things are easy for him to say. He continues to plan his summer holidays every year, as many of his patients used to do only to suddenly realise they might not live to see the next summer. ‘These people want to do something! That’s why they sometimes try alternative medicine. If they feel like they’re doing something to take back control, they can handle the treatment better as well.’

But Vanhauten secretly hopes that people don’t become too aware of the possibility of prostate cancer. So many men go to their GP to get checked out simply because their ‘neighbour had a thing’.

‘We should just let this whole thing pass us by’, he says. ‘If you don’t want prostate cancer, that’s fine. Just stay away from the hospital. Because before you know it, you’ve caught it.’