Women in science

Groundbreaking and capable

‘Finding a balance between enjoying your work and being good at it’

Roelien Bastiaanse has been a key figure in the Linguistics programme for years. Yet she ended up in this job more or less by accident. ‘I never aspired to an academic career. After I graduated I worked in a rehabilitation clinic for aphasia sufferers when Frans Zwarts (ed.: then professor of linguistics and former rector magnificus) offered me a position at the RUG. But in order to be able to work at the RUG, I first had to get my PhD.’

She became interested in aphasia, a language disorder caused by brain damage, when she was studying linguistics in Amsterdam. ‘I had an enthusiastic instructor who taught a class in the subject. Before that I’d never even heard of aphasia. But from his very first class I knew that I wanted to focus on it.’

Out of all her scientific achievements, Bastiaanse is proudest of the influence she has had on the way open brain surgery is performed. ‘Before, during awake brain surgery patients were only tested on their use of nouns, but together with my colleagues I was able to show that verbs should be included in these tests, to prevent essential parts of the brain from being cut out.’

Although she confirms her colleagues’ and friends’ description of her as very ambitious, she stresses that her career is not just about her own achievements. ‘I love the fact that I’m able to help my international PhDs build a career in their own countries. I will stay in contact with them for the rest of our lives. I truly cherish that, as well as recognition I get as their supervisor’, she says, smiling warmly.

She thinks her job is the best job there is, but becoming a professor was never her ultimate goal. ‘The true crown in my work is finding a proper balance between enjoying my work and being good at what I do.’ And she is convinced that if someone is truly good at what they do, they will automatically be noticed. ‘The position of professor should be awarded to the best candidate, be they male or female.’

‘The person in this self-portrait, Ron van Zonneveld, has had a great influence on my scientific career. He was the theoretical linguist and I was the neurolinguist: together we did a lot of research where he came up with theories and I did the experiments. This resulted in some of my greatest articles. He was a colleague turned friend, turned husband, so he is the most important person in my life in every way.’

‘Most people still think professors are men’

Marjo Buitelaar has been professor at the faculty of Theology and Religious Studies since September 2016. She is currently heading up an NWO-funded research project into the Mecca pilgrimage. When her parents moved to Saudi Arabia in her first year of her anthropology studies, it led to her interest in Islam.

‘When I visited them for the first time, I was moved by the Arabic language. Back in the Netherlands I started studying Arabic for fun’, Buitelaar says. It ended up taking her to Morocco to do field research into hammams (bath houses for women), and she later returned there for her PhD research into Ramadan.

One of her primary goals as a professor is to use her research to contribute to adequate information about Muslims. ‘I think it’s such a shame that people have such a biased view of Islam. And over the past few years this has only become worse: people associate it with violence, the suppression of women, and terrorism. But this is unfair to the majority of Muslims and it prevents their integration in the Netherlands. Because integration has to come from both sides’, she says.

The professor is thoughtful: she pauses often and chooses her words carefully. When asked which scientific achievement she is proudest of, therefore, she has to think for a bit. ‘All the research I’ve done has been published in both scientific journals and Dutch publications aimed at the general public’, she says, indicating the bookcase in her office which houses, among others, her popular scientific book on Ramadan.

Buitelaar is clear about the position of women in science. ‘I don’t think men and women can generally be said to have a different professorial style, but you do often notice different touches. And most people still think professors are men. So wittingly or unwittingly, it’s still the wanted norm. But I do think that image is changing. At our faculty, a male professor biking into the courtyard on his cargo bike which he’s just used to take his kids to school would have been unheard of twenty years ago.’

‘This mug says “I love Mecca”. There are so many varieties of “I love…” mugs. This one is a great example of how religious feelings, meanings, and practices are always shaped and therefore changed by culture. The mug also shows that no Muslim is just a Muslim. The desire to express how they feel about Islam in a format that is popular all over the world and has many varieties shows that the pilgrims who buy souvenirs like this are “children of their time”. I am incredibly fascinated by the embedding of religion in daily life.’

‘The guts to try new things’

Cisca Wijmenga is at the absolute top in her field. Her home reflects her creativity and success. It is a stately town house with an understated but stylish and modern interior. The walls are covered in stylised photographs and the furniture is austere but colourful. The Spinoza recipient researches Coeliac disease and mainly studies intestinal bacteria. ‘In addition to a new treatment method we want to develop a test which we can use to track down patients very quickly. Many people don’t even know they have the disease.’

Wijmenga’s voice is soft. ‘I really enjoy the creative process as part of my research. Figuring out how we’re going solve something so complex.’ Using ‘we’ instead of ‘I’ and her modest way of speaking are typical for Wijmenga. ‘I truly enjoy having all these young people around me. In the long run, they do all the work. All I do is follow their work and come up with ideas.’

She smiles proudly: ‘Last week we were at a conference in England where people from my group did a poster presentation. I just love seeing them work like that. They were so enthusiastic up there.’

She and her colleagues put a lot of energy into supporting her pupils. ‘When they have a presentation we make them practise it seven times, in front of the entire department. The difference between the first and the last presentations is just staggering! It’s great to see people grow in their field.’

Thanks to her many prestigious grants, Wijmenga has had a lot of room to do innovative research. It is an opportunity she feels all scientists should have. ‘In the Netherlands, if you stick out too much you’ll get your head cut off.’

She prefers to stay off the beaten path. ‘When we started our research into intestinal flora five years ago, we didn’t know anything. Today, two women in my group are considered authorities in the field. I’m so proud of the fact that we have the guts to try new things.’

‘This picture of my research group was taken during the Spinoza Prize award ceremony. I insisted on having them there: they are my inspiration.’

‘I don’t feel like a token female!’

When she was in high school, no one would have thought that Marthe Walvoort would ever become an assistant professor in chemistry. ‘I couldn’t make heads or tails of chemistry in school. I was so frustrated. I just wanted to know how it worked’, the researcher, who is quick to smile, says. ‘But I had a really cute guy as a tutor. He was a chemistry student and the way he talked about it was so inspiring. So then I started studying chemistry.’

The whiteboard in her study is adorned with the structural formulae for various sugars – her passion. During a six-month stay in Oxford she was introduced to the wonderful world of sugar molecules. ‘I had a very passionate professor and was impressed by his research. His fascination for the chemistry of sugar molecules was contagious.’

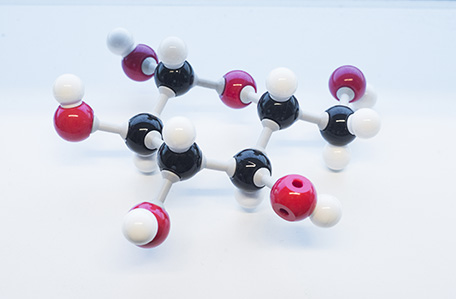

What is so great about sugar molecules? Smiling broadly: ‘They may seem simple, but even in all their simplicity they occur in nature in very complex structures. This in contrast to other substances such as amino acids that only form straight chains. That makes copying sugars a real challenge for chemists.’

After finishing her PhD in Leiden, Walvoort worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for three years. It was a very informative experience. ‘Research is held in extremely high esteem in the United States and many people at MIT are immensely driven. The pressure was really high, which means I got a lot of experience. But there’s not a lot of room left over for other things. Here at the RUG people are driven as well, but they are also more relaxed. They know work isn’t everything. In the department at MIT I was the first woman to get pregnant. Here in Groningen several people have three or four children, which is great.’

Back in the Netherlands she started working at the RUG through a Rosalind Franklin fellowship. ‘When I returned from the US there weren’t many positions available. Without that fellowship I wouldn’t be here, and I might have left academics altogether. But I don’t feel like a token female, though! You need to be really good to get one of these spots.’

Walvoort has been running her own lab in the Linnaeusborg since November 2015. She is currently doing research there together with two PhDs, a post-doctoral student, and three regular students. ‘I really enjoy supervising students and PhDs – making them see the light. To me, success means people in my group being happy.’

‘This is a 3D model of a sugar molecule. For me, it represents the simplicity as well as the complexity of sugar. And it makes it real.’

‘You have to be extraordinarily excellent’

Originally from Romania, Dorina María Buda came to Groningen in 2014 as a Rosalind Franklin fellow. She researches tourism geography and dark tourism. ‘I want to know why people travel to conflict-ridden and war-torn places. You might not expect it, but many people actually do that. The term dark tourism is a media buzzword, but I’m mainly interested in emotions. What are the experiences of these travelling tourists and locals?’

What is the objective of her research? ‘To be perfectly idealistic: world peace. But I’m realistic: if I can make even the smallest contribution to people’s understanding of this phenomenon it would be great.’ In addition, Buda is determined to put tourism research on the map. ‘In the Netherlands, tourism is limited to an applied sciences field. But I hope to be able to show that it’s more than just an industry. It’s a phenomenon worthy of scientific attention.’

Buda’s house has been decorated in a modest style: a large couch and a small dining table and a chair fill the living room. Buda works hard. Really hard: ‘In the four years since I’ve started working here I’ve published many papers, I’ve been in national journals, I received a Veni grant, got into the Young Academy, and I supervised students.’

When it comes to the position of women in science, she does not mince words. ‘As an (international) woman, you won’t make it if you’re just good, whether you’re a Rosalind Franklin fellow or not. You have to be extraordinarily excellent: innovative, original, driven. As far as I’m concerned it’s a myth that women are not as ambitious as men, or that they work less.’

She names the Veni grants as an example. ‘Approximately fifty percent of people applying for that grant are women. But the actual grants are awarded to a much smaller percentage.’ That is a phenomenon that must change, Buda feels. ‘There are so many initiatives besides the Rosalind Franklin fellowship that support women in Groningen. But the changes are being made at a snail’s pace.’

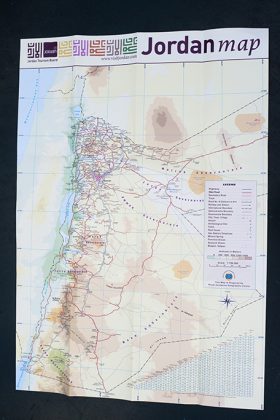

‘For me, maps are one of the accessories used in travel, tourism and wider mobility. Maps represent spatial relations linking places and peoples, and for critical tourism and cultural geographers like myself, maps are socio-cultural and political constructs.

In my work, I unpack tourism geography constructs that have shaped our assumptions about how we can know, measure and experience the world. I advocate for more embodied, emotional and affective ways of knowing and representing the world, especially in places and times of socio-political turmoil.’

This is a simplified version made for mobile view. Visit the desktop version for a rich styled article.

‘Finding a balance between enjoying your work and being good at it’

Roelien Bastiaanse has been a key figure in the Linguistics programme for years. Yet she ended up in this job more or less by accident. ‘I never aspired to an academic career. After I graduated I worked in a rehabilitation clinic for aphasia sufferers when Frans Zwarts (ed.: then professor of linguistics and former rector magnificus) offered me a position at the RUG. But in order to be able to work at the RUG, I first had to get my PhD.’

She became interested in aphasia, a language disorder caused by brain damage, when she was studying linguistics in Amsterdam. ‘I had an enthusiastic instructor who taught a class in the subject. Before that I’d never even heard of aphasia. But from his very first class I knew that I wanted to focus on it.’

Out of all her scientific achievements, Bastiaanse is proudest of the influence she has had on the way open brain surgery is performed. ‘Before, during awake brain surgery patients were only tested on their use of nouns, but together with my colleagues I was able to show that verbs should be included in these tests, to prevent essential parts of the brain from being cut out.’

Although she confirms her colleagues’ and friends’ description of her as very ambitious, she stresses that her career is not just about her own achievements. ‘I love the fact that I’m able to help my international PhDs build a career in their own countries. I will stay in contact with them for the rest of our lives. I truly cherish that, as well as recognition I get as their supervisor’, she says, smiling warmly.

She thinks her job is the best job there is, but becoming a professor was never her ultimate goal. ‘The true crown in my work is finding a proper balance between enjoying my work and being good at what I do.’ And she is convinced that if someone is truly good at what they do, they will automatically be noticed. ‘The position of professor should be awarded to the best candidate, be they male or female.’

‘The person in this self-portrait, Ron van Zonneveld, has had a great influence on my scientific career. He was the theoretical linguist and I was the neurolinguist: together we did a lot of research where he came up with theories and I did the experiments. This resulted in some of my greatest articles. He was a colleague turned friend, turned husband, so he is the most important person in my life in every way.’

‘Most people still think professors are men’

Marjo Buitelaar has been professor at the faculty of Theology and Religious Studies since September 2016. She is currently heading up an NWO-funded research project into the Mecca pilgrimage. When her parents moved to Saudi Arabia in her first year of her anthropology studies, it led to her interest in Islam.

‘When I visited them for the first time, I was moved by the Arabic language. Back in the Netherlands I started studying Arabic for fun’, Buitelaar says. It ended up taking her to Morocco to do field research into hammams (bath houses for women), and she later returned there for her PhD research into Ramadan.

One of her primary goals as a professor is to use her research to contribute to adequate information about Muslims. ‘I think it’s such a shame that people have such a biased view of Islam. And over the past few years this has only become worse: people associate it with violence, the suppression of women, and terrorism. But this is unfair to the majority of Muslims and it prevents their integration in the Netherlands. Because integration has to come from both sides’, she says.

The professor is thoughtful: she pauses often and chooses her words carefully. When asked which scientific achievement she is proudest of, therefore, she has to think for a bit. ‘All the research I’ve done has been published in both scientific journals and Dutch publications aimed at the general public’, she says, indicating the bookcase in her office which houses, among others, her popular scientific book on Ramadan.

Buitelaar is clear about the position of women in science. ‘I don’t think men and women can generally be said to have a different professorial style, but you do often notice different touches. And most people still think professors are men. So wittingly or unwittingly, it’s still the wanted norm. But I do think that image is changing. At our faculty, a male professor biking into the courtyard on his cargo bike which he’s just used to take his kids to school would have been unheard of twenty years ago.’

‘This mug says “I love Mecca”. There are so many varieties of “I love…” mugs. This one is a great example of how religious feelings, meanings, and practices are always shaped and therefore changed by culture. The mug also shows that no Muslim is just a Muslim. The desire to express how they feel about Islam in a format that is popular all over the world and has many varieties shows that the pilgrims who buy souvenirs like this are “children of their time”. I am incredibly fascinated by the embedding of religion in daily life.’

‘The guts to try new things’

‘The guts to try new things’

Cisca Wijmenga is at the absolute top in her field. Her home reflects her creativity and success. It is a stately town house with an understated but stylish and modern interior. The walls are covered in stylised photographs and the furniture is austere but colourful. The Spinoza recipient researches Coeliac disease and mainly studies intestinal bacteria. ‘In addition to a new treatment method we want to develop a test which we can use to track down patients very quickly. Many people don’t even know they have the disease.’

Wijmenga’s voice is soft. ‘I really enjoy the creative process as part of my research. Figuring out how we’re going solve something so complex.’ Using ‘we’ instead of ‘I’ and her modest way of speaking are typical for Wijmenga. ‘I truly enjoy having all these young people around me. In the long run, they do all the work. All I do is follow their work and come up with ideas.’

She smiles proudly: ‘Last week we were at a conference in England where people from my group did a poster presentation. I just love seeing them work like that. They were so enthusiastic up there.’

She and her colleagues put a lot of energy into supporting her pupils. ‘When they have a presentation we make them practise it seven times, in front of the entire department. The difference between the first and the last presentations is just staggering! It’s great to see people grow in their field.’

Thanks to her many prestigious grants, Wijmenga has had a lot of room to do innovative research. It is an opportunity she feels all scientists should have. ‘In the Netherlands, if you stick out too much you’ll get your head cut off.’

She prefers to stay off the beaten path. ‘When we started our research into intestinal flora five years ago, we didn’t know anything. Today, two women in my group are considered authorities in the field. I’m so proud of the fact that we have the guts to try new things.’

‘I don’t feel like a token female!’

‘I don’t feel like a token female!’

When she was in high school, no one would have thought that Marthe Walvoort would ever become an assistant professor in chemistry. ‘I couldn’t make heads or tails of chemistry in school. I was so frustrated. I just wanted to know how it worked’, the researcher, who is quick to smile, says. ‘But I had a really cute guy as a tutor. He was a chemistry student and the way he talked about it was so inspiring. So then I started studying chemistry.’

The whiteboard in her study is adorned with the structural formulae for various sugars – her passion. During a six-month stay in Oxford she was introduced to the wonderful world of sugar molecules. ‘I had a very passionate professor and was impressed by his research. His fascination for the chemistry of sugar molecules was contagious.’

What is so great about sugar molecules? Smiling broadly: ‘They may seem simple, but even in all their simplicity they occur in nature in very complex structures. This in contrast to other substances such as amino acids that only form straight chains. That makes copying sugars a real challenge for chemists.’

After finishing her PhD in Leiden, Walvoort worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for three years. It was a very informative experience. ‘Research is held in extremely high esteem in the United States and many people at MIT are immensely driven. The pressure was really high, which means I got a lot of experience. But there’s not a lot of room left over for other things. Here at the RUG people are driven as well, but they are also more relaxed. They know work isn’t everything. In the department at MIT I was the first woman to get pregnant. Here in Groningen several people have three or four children, which is great.’

Back in the Netherlands she started working at the RUG through a Rosalind Franklin fellowship. ‘When I returned from the US there weren’t many positions available. Without that fellowship I wouldn’t be here, and I might have left academics altogether. But I don’t feel like a token female, though! You need to be really good to get one of these spots.’

Walvoort has been running her own lab in the Linnaeusborg since November 2015. She is currently doing research there together with two PhDs, a post-doctoral student, and three regular students. ‘I really enjoy supervising students and PhDs – making them see the light. To me, success means people in my group being happy.’

‘This is a 3D model of a sugar molecule. For me, it represents the simplicity as well as the complexity of sugar. And it makes it real.’

‘You have to be extraordinarily excellent’

‘You have to be extraordinarily excellent’

Originally from Romania, Dorina María Buda came to Groningen in 2014 as a Rosalind Franklin fellow. She researches tourism geography and dark tourism. ‘I want to know why people travel to conflict-ridden and war-torn places. You might not expect it, but many people actually do that. The term dark tourism is a media buzzword, but I’m mainly interested in emotions. What are the experiences of these travelling tourists and locals?’

What is the objective of her research? ‘To be perfectly idealistic: world peace. But I’m realistic: if I can make even the smallest contribution to people’s understanding of this phenomenon it would be great.’ In addition, Buda is determined to put tourism research on the map. ‘In the Netherlands, tourism is limited to an applied sciences field. But I hope to be able to show that it’s more than just an industry. It’s a phenomenon worthy of scientific attention.’

Buda’s house has been decorated in a modest style: a large couch and a small dining table and a chair fill the living room. Buda works hard. Really hard: ‘In the four years since I’ve started working here I’ve published many papers, I’ve been in national journals, I received a Veni grant, got into the Young Academy, and I supervised students.’

When it comes to the position of women in science, she does not mince words. ‘As an (international) woman, you won’t make it if you’re just good, whether you’re a Rosalind Franklin fellow or not. You have to be extraordinarily excellent: innovative, original, driven. As far as I’m concerned it’s a myth that women are not as ambitious as men, or that they work less.’

She names the Veni grants as an example. ‘Approximately fifty percent of people applying for that grant are women. But the actual grants are awarded to a much smaller percentage.’ That is a phenomenon that must change, Buda feels. ‘There are so many initiatives besides the Rosalind Franklin fellowship that support women in Groningen. But the changes are being made at a snail’s pace.’

‘For me, maps are one of the accessories used in travel, tourism and wider mobility. Maps represent spatial relations linking places and peoples, and for critical tourism and cultural geographers like myself, maps are socio-cultural and political constructs. In my work, I unpack tourism geography constructs that have shaped our assumptions about how we can know, measure and experience the world. I advocate for more embodied, emotional and affective ways of knowing and representing the world, especially in places and times of socio-political turmoil.’

‘The guts to try new things’

‘The guts to try new things’ ‘I don’t feel like a token female!’

‘I don’t feel like a token female!’

‘You have to be extraordinarily excellent’

‘You have to be extraordinarily excellent’