Research during the corona crisis

Everything UG scientists have discovered

Why does the coronavirus make some people really sick while others are barely affected? Geneticist Lude Franke suspected the secret lay in people’s genes and quickly set up a study.

The first results are promising: Franke and his research team may have found DNA locations that affect whether or not a person becomes seriously ill. They are currently mapping these out. ‘This is only the start, we still have a lot of work to do’, says Franke.

Once everything is mapped out, they can figure out what’s going wrong. ‘Which genes are involved? Which tissues, which cells? Which biological processes are being disrupted?’ Once they know that, they can see if there’s any (existing) medication that is effective in treating Covid-19.

Questionnaire

In his research, Franke is collaborating with UG Lifelines and the Aletta Jacobs School of Public Health. They asked participants in the Lifelines project to fill out an extensive questionnaire. They got approximately sixty thousand responses.

Young people who live along felt very lonely

The questionnaire covered a range of subjects. One of those was the effect of the coronavirus on the participants’ well-being. ‘One interesting result was that relatively young people living alone were feeling very lonely during the corona crisis. But as the symptoms lessened, so did people’s mental distress’, says Franke.

‘This is a unique situation’, he says. ‘We set up the study so quickly. We were ready to go within three weeks. That’s never happened to me before.’

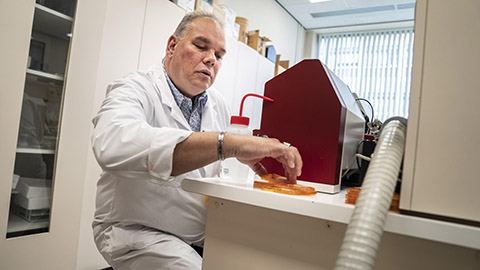

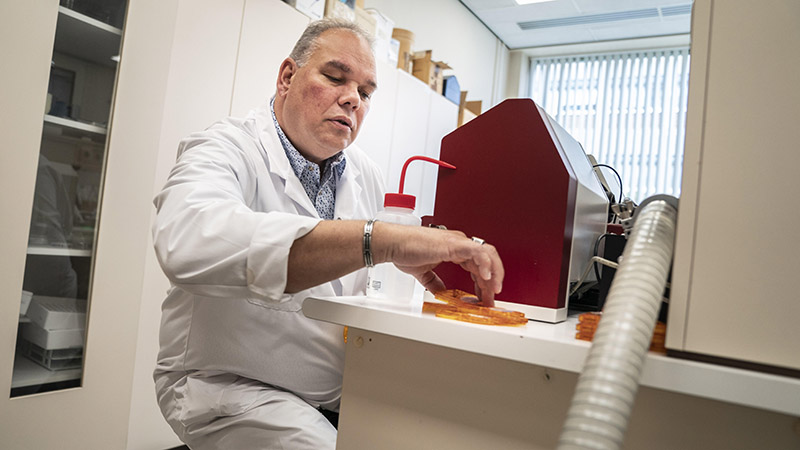

Inhaler

Researcher of pharmaceutical technology Paul Hagedoorn also moved quickly. He has been working on a treatment from the moment the virus arrived in the Netherlands. He’s been focusing on an existing drug, trying to alter the way it’s being administered: through an inhaler rather than as a pill.

‘We developed this inhaler to administer the correct dosage of the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine’, he says. ‘It can be discarded after a single use, to prevent infection.’

After three months, the study is looking promising. The first clinical batch has been manufactured by PureIMS in Roden and is ready for use. ‘The drug made it through the final round of quality control and has been released.’

Hagedoorn and his fellow researchers hope to be able to test the drug on volunteers, but they need permission from the medical ethics committee. ‘The next phase involves proving that it works, but we’re not there yet.’

Decrease infection

He believes administering the drug through an inhaler will make a difference. ‘We truly believe that we can decrease the chance of infection and lessen the severity of the symptoms.’ The drug might just inhibit the response the body has to the virus.

Give us time to show that this drug has potential

Hagedoorn hasn’t let the backlash against chloroquine discourage him. Several studies supposedly proved that the drug was ineffective against corona. ‘But all those studies are based on the drug being administered as a tablet, when the method is key’, he explains. ‘The inhaler deposits the drug directly into a person’s lungs, which means we’d need a much lower dose to reach the necessary active concentrations. And the chance of side effects becomes much smaller.’

Oral administration will never lead to the necessary concentration in the lungs, says Hagedoorn. He knows public opinion is not in his favour. ‘But give us the time and space to show that this drug has potential. We just need to administer it correctly.’

Leadership

The corona crisis has also presented a unique opportunity for research for Janka Stoker, professor of leadership and organisational change. How do leaders respond to a crisis like this? What’s considered a good leader in times of crisis? She worked together with Harry Garretsen from the UG and Joris Lammers at the University of Cologne.

The study involved approximately 750 participants, both managers and employees. The most prominent result was that in this corona crisis, leaders are less directive. ‘In other words, not as leading. They admit to it themselves and that’s also how their employees see it.’ Stoker says it makes sense, since so many employees are working from home now.

‘Interestingly enough, managers say they’re delegating less during this crisis, while their employees say they see no difference with how it was before. That’s fascinating’, says Stoker. ‘It would mean the image managers have of themselves is wrong. My tip to them would be to talk to their employees. That’s more important than ever right now.’

Masculine and feminine

What do employees consider a good leader in a crisis? What are the characteristics they’re looking for? The study has shown that employees favour managers that display both masculine traits (dominant, decisive) and feminine traits (caring, sensitive, understanding).

Employees prefer masculine traits in leaders

‘They felt the same before the corona crisis’, says Stoker. This doesn’t mean that employees prefer men over women, she emphasises. ‘But if you ask them to describe their ideal leader, they prioritise masculine traits over feminine ones.’

Nevertheless, something interesting has happened, says Stoker. ‘We did a study on the ideal leader ten years ago, right after the financial crisis. It turned out that, while people still prefer masculine traits, they now appreciate feminine traits more than they did back then.’ In other words, ten years ago, the ideal leader was a lot more masculine than they are now.

Mental health

Behavioural psychologist Pontus Leander knew he had to do something when the coronavirus hit. His goal was to find out how people felt and behaved during the pandemic. He now heads up a worldwide study that involves approximately a hundred researchers. Approximately sixty thousand people filled out the questionnaire, a process which took twenty minutes. ‘It’s unique to get that many responses to such a long questionnaire.’

People afraid of the virus often have poor mental health

The study is still ongoing, but Leander already has some results. His research team found out that people who are worried they’ll catch the virus tend to have poor mental health. ‘It’s also apparent in their negative emotions.’

The study has also shown that people who trust the government to fight the coronavirus take more action to protect themselves and others. ‘They practise social distancing, self-isolate, and wash their hands more often. It also appears they make more sacrifices to protect others and donate more money when asked.’

People who don’t feel like they’re part of society tend to not stick to the rules as much. ‘They feel like outsiders that no one listens to anyway and don’t think they should listen to anyone else either.’

Crisis communication

How does this information help us? ‘It’s potentially very valuable to public health communication’, says Leander. ‘What is the best way to communicate with society in a crisis like this?’ They’re also cataloguing the results per country. ‘It’s so we can see which policies work and which measures don’t.’

It’s the biggest project he’s ever been a part of. ‘I work a hundred hours a week sometimes. It’s literally causing me to lose sleep, but it’s totally worth it’, he says. Since a study like this had never been done before, everything was new to the researchers. ‘We’re writing down every single step in the process. We’re making a handbook in case something like this ever happens again.’