How to get all the best ideas

Brainstorming like a boss

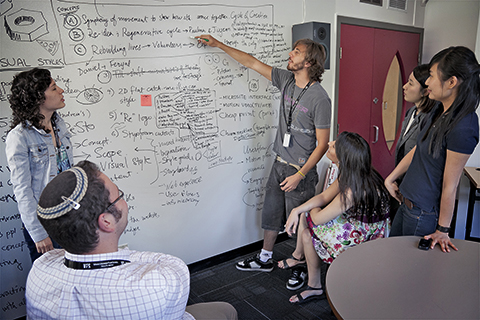

Method 1: Reserve a room and get together to discuss all your amazing, super creative ideas.

If you like brainstorming in a group with other people, you’re definitely not the only one. Whether you work for a multinational corporation looking to launch a new product, a university in need of a theme for its upcoming anniversary, or a fraternity trying to recruit new members, you probably enjoy brainstorming sessions with other people. ‘That’s actually really interesting’, says RUG psychologist Kiki de Jonge. ‘We realised a long time ago that this doesn’t actually result in the greatest output of creative ideas. But everyone keeps doing it because we feel it’s the best way to do it.’

In other words, forego getting together in that room, because it turns out we actually come up with fewer good ideas as a team than if we all go it alone. ‘That’s because there’s more constant flow in a group setting’, says De Jonge. ‘If you’re trying to come up with ideas on your own you eventually get stuck.’ That is an uncomfortable feeling.

In a group session, there’s always someone saying something. But that comes with its own disadvantages. ‘Remarks from other people distract you from your own thoughts’, says De Jonge, ‘which can lead you to forget your own ideas.’

Not to mention the other people in the group who don’t let others finish speaking, people who shoot down ideas without properly listening to them, or people who are simply too shy to speak up.

Method 2: E-mail all the members in your group assignment. Everyone will come up with as many good ideas separately. This will make sure no one gets distracted.

This method is certainly better than the first one, says De Jonge, but it’s still not the best way to come up with creative ideas. Sure, you won’t get interrupted or distracted by your teammates, but you’re also missing an essential characteristic of the group brainstorming session: when your thoughts get stuck, there won’t be anyone to get them going again.

‘Other people’s remarks or suggestions can lead to new associations, allowing you to come up with a bunch of new ideas’, says De Jonge.

Method 3: E-mail all the members in your group assignment. Everyone comes up with as many good ideas as possible and puts them in a shared drive. If you get stuck, you can have a look at the others’ ideas to get going again.

This is the best way to come up with ideas, says De Jonge. It has all the advantages of the two earlier methods, and none of the drawbacks. ‘People who got input from other people during the brainstorming sessions came up with thirty to thirty-five ideas each’, she says. ‘Without that input, people got stuck at sixteen ideas.’

She thinks we should be able to design software that presents people with the exact ideas they need to stimulate the brainstorming process (see box). It would provide out-of-the-box ideas for autonomous thinkers and more commonplace ideas for people who prefer structure.

However, there is still one little drawback to this method: brainstorming with a team of other people is a lot more fun than alone in front of a computer. De Jonge is aware of this. ‘If you must work in a group’, she says, ‘you could try using sticky notes. Write your ideas down in silence and stick them to a big board.’

What constitutes a creative idea?

Corporations are always looking for creative and innovative ideas. They need them to stay ahead of the competition. But when is an idea truly creative? How can you make sure that people come up with as many creative ideas as possible?

Ideas are creative, says organisational psychologist Kiki de Jonge, when they’re both innovative and applicable. Otherwise they’re just no use. These are not new concepts. But, says De Jonge, who is receiving her PhD for her research into creativity and flow on September 9, the people who evaluate the ideas also play a role.

Someone who needs structure to flourish will not think that out-of-the-box ideas are very creative. ‘People like that will judge them as disruptive and nonsensical’, says De Jonge. Independent and autonomous thinkers will probably reject more common ideas.

De Jonge studied how to stimulate creativity by having her test subjects judge ideas. She also asked them to brainstorm on the question of how to make people healthier.

Innovative thoughts

De Jonge found out that the difference between structure lovers and autonomous workers applied here as well. ‘In every group, we made approximately a hundred people take part in an electronic brainstorming session’, she says. ‘They thought they were working together, but we were feeding them ideas on the computer screen.’

It turned out that people who prefer structure did their best brainstorming when they were presented with ‘ordinary’, non-innovative ideas; suggestions such as: go to the doctor more often, or: take the stairs instead of the elevator. ‘This will lead them to come up with other ideas they hadn’t thought of before’, De Jonge explains. The more innovative finds would block this process.

Conversely, the more autonomous types found innovative thoughts to be more stimulating. ‘Such as: let’s add vitamins to chewing gum’, says De Jonge.

She thinks it’s because autonomous people don’t like their thought process being disrupted. When it is interrupted, for example by an idea they feel is boring, this annoys them. ‘Out-of-the-box suggestions are still annoying to them, but at least they’re worth it’, says De Jonge.

That’s important for the final result. Presenting the right idea to the right person means that both structural people and autonomous thinkers produce the maximum number of ideas. And they’ll have a good time, too.