proof of god

Astonish and admire

In 2014, an unusual question found its way to astronomy professor Peter Barthel. Professor, does God exist? asked then 7-year-old Anco.

Barthel’s answer received a lot of media attention and published in the newspaper Trouw.

Fans praised Barthel’s open-minded view, while the world of theology criticised him.

For Barthel, this was reason enough to elaborate on his answer. On Friday, 24 February, his definitive answer will be published as a book.

Barthel is convinced that everything revolves around astonishment.

To find the answer to the question of whether there is a God, you have to think about your role and place in the world.

Reading time: 8 minutes (1500 words)

Astronomy professor Peter Barthel is a passionate man. On 24 February his essay ‘Professor, does God exist?’ will be published. Playing with a beer coaster, he starts talking before he has even been asked a question. ‘Scientists should be aware of their privileged position.’ With a questioning look: ‘Did you know that you pay three euros each year so I can do my job? Surely you should get something in return for that?’

With ‘something in return’, Barthel means scientific knowledge. After his PhD in Leiden and his post-doctoral career in the United States he landed at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in Groningen in 1988. He works on objects and processes in the larger universe – a hard, exact science – but also on science communication. That, plus the fact that he sometimes participates in public debates about science and religion, led to him being asked an unusual question in 2014.

Question

‘Professor, does God exist?’ asked 7-year-old Anco. People who wanted to do so could ask the university questions because of its 400th anniversary. Anco’s question went past different theologians for a while, until then dean Geurt Henk van Kooten decided the question should not be answered by a theologian, but by astronomer Barthel.

Scientist Barthel, himself a ‘critical member’ of the Protestant Church, gave it a lot of thought and discussed it with theologians Carel ter Linden, Klaas Hendrikse, and Harry Kuitert. ‘No, God does not exist as a person who lives in heaven, rules the world, and takes care of you. All the good and beautiful things in this world, that is what I would call God. God exists in how you and I live. People who want to take care of each other: that is where you can see something of God’, he concluded his answer to Anco. In a lecture during the Night of Arts and Science in 2014 he expounded that answer.

Polemic

Newspaper Trouw published the letter, causing an honest-to-goodness polemic. Several theologians rejected his progressive vision. For example, Barthel dismisses the Creation narrative. But the majority of the reactions he got were laudatory. The astronomer was praised for his ‘open and clear view’. Reason enough for Barthel to elaborate on his answer and disseminate it as a book.

‘My answer arose from a process, from a quest. Because I was giving lectures I often got remarks from my audience. Those questions got me thinking, and talking.’ Initially, his ultimate answer was not even remotely clear, says Barthel, his eyes twinkling. ‘But it’s really quite simple.’

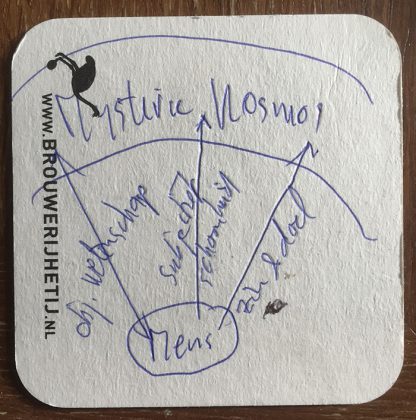

Barthel’s beer coaster. The three arrows are the ways we can approach the world and that all-encompassing mystery.

He starts drawing on the beer coaster in front of him. Three parallel arrows. Next to these arrows, he writes the words science (objective), beauty (subjective), and sense and goal. The arrows all point upward, to The Big Mystery/cosmos. For Barthel, the universe is an important part of that large mystery. It is also the reason he became a scientist. The three arrows are the different ways we can approach the world and that all-encompassing mystery.

‘First and foremost, scientists work on experiments to determine the truth. We are working on the letter of the universe’, Barthel explains. ‘The goal of scientific research is an increase in collective understanding. But people can also be astonished at its mystery in their own ways: we don’t all have to think the same things are beautiful. I call that the spirit of the universe.’

Astonishment

The last arrow represents sense and goal. You could call it religion, but you do not have to. ‘It’s about how that astonishment affects you. You can shrug at that, but I think people are basically obligated to think about their role and their place in the world and in the cosmos.’ The world cosmos comes from ancient Greek and means order. ‘But also beauty. That is why I love the word so much: to me, it encompasses everything’, he says.

Has Barthel determined his role in the world? He grins. ‘I want everyone to have their due. That everyone is helpful and brings positivity into the world. That’s what life is about.’

According to Barthel, it does not matter which views you espouse. ‘Every religion has good points. It’s about that wonder, that astonishment. That is at the core of everything’, the astronomer says. ‘Albert Einstein described himself thusly: “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.” That’s how I see myself, too.’

No conflict

Barthel squarely rejects the notion that there is a conflict between religion and science. ‘Scientifically speaking, there is absolutely no proof that there is a God in the sense of an engineer with a grey beard who created the world. But that’s not what it’s about. Why does this world exist – that’s what I’m concerned with. Astonishment is at the core of everything, and finding an answer to that astonishment.’

It is really quite simple. Call it God, call it spirituality, or call it astonishment. Call it beauty. ‘Faith is not that important, it’s about what you do’, Barthel says. He winks: ‘If everyone stuck to that, we might get God’s Kingdom on earth.’

First copy

On 1 March Barthel will hand the first copy of his book to Anco, now ten years old, at the Riemer bookstore in the Oude Ebbingestraat. Scientific journalist René Fransen and RUG professors Geurt Henk van Kooten (theology) and Franjo Weissing (biology) will discuss Barthel’s answer with the audience.

The event is free and doors open at 7.30 p.m.

The proceeds of the book will be donated to the Eric Bleumink Fund (EBF), which gives out grants to talented students from developing countries.