What sleep deprivation does to your brain

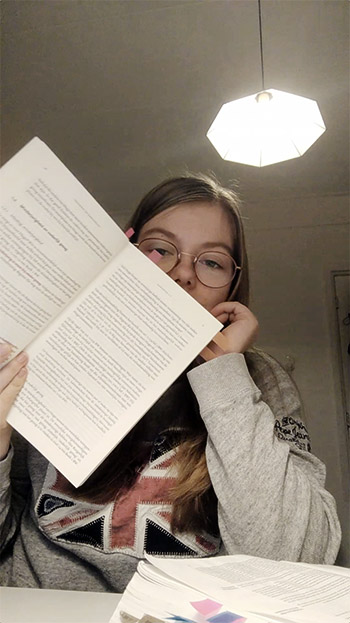

Pulling an all-nighter

9.30 p.m.

Today was not a productive day. But my Civil Rights 1 exam waits for no man, and it is coming soon. I take another look at the clock and consider pulling an all-nighter. Surely I should be able to pull off studying for the whole night?

It’s 9:45 when I prepare myself to work. I’ve made a large pot of tea and a plate of cookies. Armed with a highlighter, I get to it. I can do this.

Expert

‘You do understand that I have to discourage doing this?’ neurobiology lecturer Peter Meerlo asks. He warns that studying all night will have a negative impact on my hippocampus, the part of my brain that stores information and forms memories. ‘The hippocampus is extremely sensitive to sleep deprivation.’

Although studying an hour past your bedtime won’t do much harm, Meerlo says, I’ll definitely start feeling the effect if I stay up all night. I’ll become less alert and increasingly tired.

11.00 p.m.

After fifteen minutes, I turn back to my book. But it’s not as easy. I’m feeling kind of chilly and I’m having a hard time concentrating on the material. I force myself to keep going; I have to learn this stuff.

Expert

‘The brain is continuously engaged in two processes at once’, neuroscientist Robbert Havekes says. He studies the influence of sleep deprivation on the hippocampus. ‘On the one hand, your brain is busy actively soaking up all that’s happening in the present moment.’

For example, when you’re talking to your roommate or biking home from class. ‘On the other hand, it’s involved in a process of consolidation, processing information you soaked up earlier.’ For instance, what your professor said during a lecture earlier that day. This is a process you’re not consciously aware of.

The first, active processing of information goes into standby-mode when you sleep. You’re out cold and don’t pick up any new information. But the consolidation process doesn’t shut off when you sleep; your brain processes what happened during the day.

Sleep is important because it allows all the information you absorbed during the day to be ‘converted’ into stored information or memories. But you need your rest during the day as well: ‘If you don’t take a break after every 45 minutes of studying’, you “overflow”’, says Havekes. ‘You stop being able to take in information as easily as before.’

Midnight

The material won’t stick; I have to read every sentence three times before I understand it. I’m starting to panic. If I can’t even understand this basic stuff, how will I ever get the rest?

Expert

My experience aligns exactly with Meerlo’s predictions: ‘Your prefrontal cortex is becoming more sluggish. This part of your brain is in charge of regulation your emotions, among other things. If the area is less active due to fatigue, you become more impulsive. Your emotions become uninhibited.’

That’s great if you’re with friends and you’re going out and staying up all night, but it’s less convenient during an all-nighter like this. I’m even more stressed about the exam than I already was.

1:30 a.m.

In spite of the stress, I keep going. I’ve put a pillow against my back to be more comfortable. The caffeine worked wonders; I’m raring to go. I read, highlight, and summarise. All in all, I’m feeling pretty productive. Fatigue? I don’t know her.

But around one-thirty, I hit another slump. Whenever I look down at the book, it’s as if gravity is pulling on my eyelids. They close. I decide it’s time for a snack break. A grilled cheese sandwich and a cup of soup should do the trick. Once I’ve eaten my way out of the slump, I return to my books.

Expert

‘A study using mice showed that after five to six hours of sleep deprivation, your neurons start breaking their connections to each other’, says Havekes. A neuron is a nerve cell, forming the basis of your nervous system. ‘The neurons in the hippocampus are important if you want to absorb information when you study. But because those connections are broken if you’re not sleeping, the information can’t be processed.’

One of the proteins involved in breaking the connections to other neurons is cofilin, which becomes overactive when you’re suffering from sleep deprivation. ‘These broken connections can be repaired through sleep’, says Havekes, ‘but it’s already too late to consolidate any information you picked up earlier.’

02:00 a.m.

03:00 a.m.

I fell asleep on my book. It’s three in the morning as I drag my tired body over to the couch to continue reading. I’m not sure that’s such a good idea though; the couch is much more comfortable than my hard desk chair. Nevertheless, I allow myself a little comfort. A passage marked in bright yellow shows me where I left off. I soldier on.

Expert

It turns out my biological clock is upset. ‘Most people have the hardest time around three in the morning’, says Meerlo. ‘They tend to perk up a little around four or five, because that’s when their biological clock starts back up. If you’d gone to sleep like any other night, that’s when your body starts waking up again.’

After that high, however, is the inevitable low. ‘The need for sleep becomes so great that it pretty much takes over. It’s best to stop studying when this happens, because you will not take in any information’, Meerlo predicts.

05:00 a.m.

What should you do?

It turns out an all-nighter is never a great idea. The more neuronal connections you wreck, the less information you take in. What can help is going over material you’ve already learned right before you go to sleep. This activates the consolidation process, allowing your brain to process the information while you sleep. You can study while you snore.

Havekes recommends studying at 45-minute intervals, taking a fifteen-minute break in between to do something completely different, like walking your dog or taking a quick power nap. It doesn’t matter what you do as long as you temporarily stop the flow of information to allow your brain to activate the consolidation process.