Not much has changed

Still afraid of your landlord

‘I can’t believe that in a country like the Netherlands, famed for its hospitality, people are actually fleecing students’, says Daria Cieślak. Over the course of thirty months, the Polish student of international business and her roommates together paid more than seven thousand euros in excess rent. They are not the only ones.

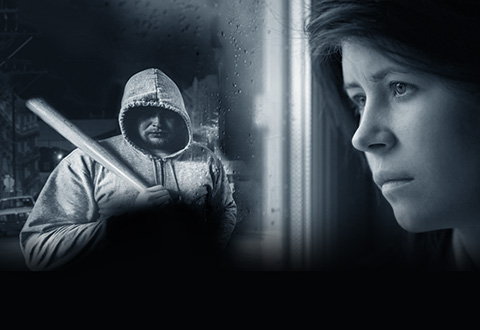

If you’re looking for students who’ve had issues with malicious landlords, you don’t have to go far: a few messages on Facebook and WhatsApp groups easily got me thirty responses. Yet only four students were willing to have their name published, and only ten others wanted to talk to me at all. Most of them refuse to have their tales published, as they’re worried about retaliation.

What are the most common complaints? Intimidation, extremely high rent and service charges, overdue maintenance, and weird demands they have no choice but to comply with.

Overpaid

Daria came to the Netherlands in 2015 and was offered a room for 355 euros a month. ‘It sounded reasonable’, she says. ‘A sixteen square metre room, close to the university. They’d just redone the kitchen.’

After a few months, however, the building changed owners and a new real estate agency started managing the property. ‘We didn’t know about this until we started getting letters from DC Wonen, a company I’d never heard of.’ The rent stayed the same, so Daria assumed everything was fine. ‘Then we read on Sikkom that some rental agencies didn’t treat their tenants very well at all. DC Wonen was on the list.’

Over the course of thirty months, I paid twelve hundred euros in excess

By then it was 2018, and Daria and her roommates decided to take a closer look at their rent. ‘We contacted Protega, a law firm that helped us with our contracts. They concluded that we were all paying approximately sixty euros too much per month. I lived in that house for thirty months, and during that time I paid twelve hundred euros in excess.’

She was furious: ‘I’m from a Eastern European family. It’s not easy for them to pay all my costs here.’

Service charges

They had been overcharged on the service costs, the money they paid for gas, electricity, water, and other services that were added to the base rent. DC Wonen said the current owner of Daria’s house didn’t know how high the service charges for the property were supposed to be. ‘In the years since he purchased the property, he hasn’t checked on these charges, nor has he kept count or saved the invoices’, the real estate firm wrote in an e-mail. ‘Protega notified him of this and he talked to them.’

The excess service charges, a total of seven thousand euros, have since been paid back. ‘It’s a large amount’, DC Wonen admits, but divided over six rooms and several years, ‘it’s not that much’.

You don’t have to be your landlord’s friend

Daria’s story had a happy ending. But many landlords use service cost fraud as a way to make extra money, and there are very few students who actually take action.

Denise Zonnebeld, founder of rental advice agency Frently, estimates that only two percent of students actually gets help. ‘They don’t know about us’, says Zonnebeld. ‘Or they’re afraid of their landlord, which they shouldn’t be. They have a business relationship with their landlord. They don’t have to be his friend.’

Taking action is definitely worth it. According to Zonnebeld, students on average overpay by 683 euros a year. Tenants should receive a final statement at the end of the year from their landlord. If they paid more than he spent, they should get the excess back. Unfortunately, that rarely happens.

Intimidation

The fact that students are hesitant to bring up high rent or other issues is understandable, though. After all, there are plenty of stories about landlords who bully their tenants out of their rooms or threaten to send people to beat them up. In 2017, landlord Wim de Vries locked a student in her room in the Folkingestraat by screwing her door shut. He was sentenced to community service. Between 2012 and 2017, 58 students made a report against their landlord.

Zonnebeld also had issues with her landlord. It inspired her to start Frently, but that had consequences.

‘Landlords weren’t used to people standing up to them. They didn’t like it’, says Zonnebeld. ‘When I had just started, someone threw a brick through my window. That was pretty scary. And someone stole my scooter two weeks after I got it. A lawyer I was friends with told me that one of the landlords had taken it.’

Nevertheless, Zonnebeld will continue to provide help to students. ‘People might hear my story and think it’s not worth doing anything. But I’ve handled more than six thousand cases and it only went wrong once.’ Plus, she emphasises, it’s worth it. ‘The average rent reduction is 157 euros and 53 cents. We can really make a change.’

Con

In addition to the service charges, there are other ways landlords con students out of their money. An anonymous student received an invoice from his landlord for replacing a rotted window frame. Irish journalism student Tadhg O’Sullivan encountered a room that looked nothing like what he thought he’d be renting.

When he arrived in town, his room in a student flat at the Vondellaan wasn’t ready yet. He thought he would be sharing a kitchen with five people, but instead it was being used by 24 people at once, and he kept seeing rats scurrying around. ‘We had issues all the time’, says Tadhg. Eventually, he left the flat.

The story of TadGh

The municipality of Groningen, after consultation with the Groninger Studentenbond (GSb), implemented a renters permit to prevent these kinds of abuses. Should a landlord or intermediary misbehave, their permit can be revoked. This only works when students actually complain, though. Unfortunately, they hardly do.

Tackling landlords is difficult, even if there is a pattern

The Meldpunt Ongewenst Verhuurgedrag (a hotline where student can complain) has received approximately forty complaints since its inception. That’s not very much, says Jan Willem Leeuwema, GSb chairman. ‘Calling the hotline is scary, since these students are complaining about people who are responsible for the roof over their heads. The shortage of rooms also means not everyone will complain.’

Anyone who did call the hotline probably won’t be seeing results any time soon. ‘Right now, they’re just registering the complaints, says Esse Velthuis with the municipality of Groningen. ‘We’re working on setting up an enforcement protocol. Tackling problematic landlords is difficult, even if there’s a pattern of complaints against them.’

Reference

What makes it even more difficult to take action against malicious property owners is that some ask for a reference from a previous landlord. The reference says whether a tenant behaved properly.

Johannes (a pseudonym) was also asked for a reference by his landlord. ‘You don’t have to, of course, but if I don’t submit one, there are ten other candidates who will take the room. That’s why I never complained about the excess rent to my previous landlord, or about the service charges he didn’t pay us back. Or the fact that the rooms were much smaller than he’d advertised.’

Johannes is also still waiting for the deposit from his previous room. ‘The landlord refused to pay it back because the kitchen looked like it had been used. Tenants feel extremely powerless, because we’re dependent on our landlords even after we’ve left. I’d rather bite my tongue than try to get what I’m owed. I don’t want to piss off my landlord.’