Navigating Zwarte Piet

Conversations with a five-year-old

There were so many of them, hung up in a line from one corner of the room to the other. The jolly fools smiled down at us with their too-red mouths, their stupid googly eyes rolling about in every direction with an expression of wild disbelief that must have matched my own.

Kids swarmed around me as I stood blocking the doorway of my daughter’s groep twee classroom. ‘Is one of those yours, kiddo?’ I asked, as calmly as I could. She pointed with pride to the wobbly round face she had cut out of black construction paper with her teensy, clumsy, harmless hands. Her very own Zwarte Piet. My stomach dropped.

No warning

Blackface minstrelsy

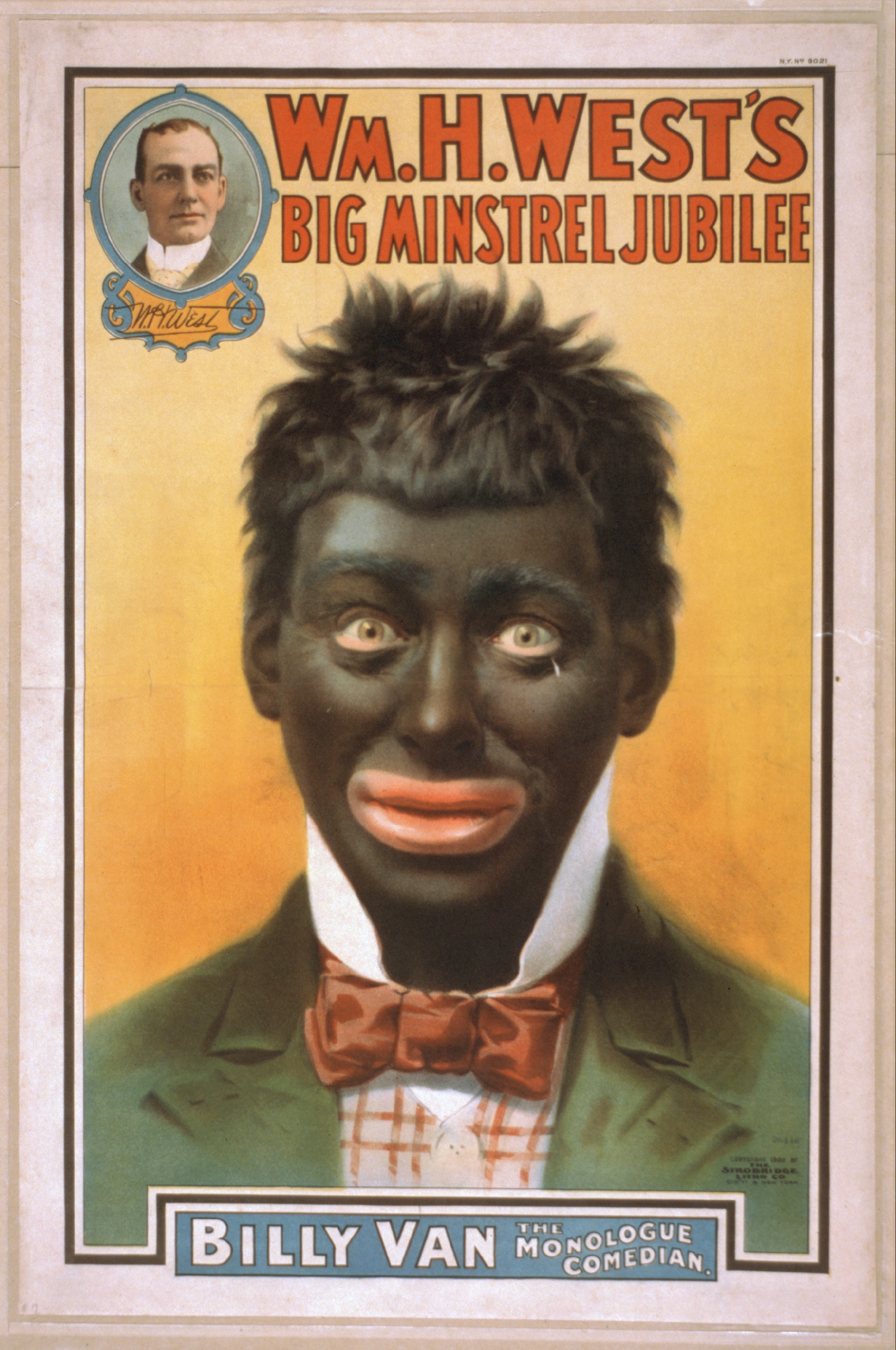

Encountering blackface can be a shock for many internationals. Blackface minstrelsy, born in American music halls in the 19thcentury but practiced all over the world, depicted black people as mentally and socially inferior.

It was an ‘all in good fun’ form of entertainment that spread racist attitudes and stereotypes so well they continue to resurface in our social interactions, legal policies, and entertainment today.

Zwarte Piet, with his exaggerated features, dandified clothes, and entertaining antics, is a caricature you both laugh at and are implicitly afraid of (he’ll snatch your kids). His similarities with blackface minstrel characters are difficult to ignore.

It was our first Sinterklaas season since moving to the Netherlands a few months before. We enrolled my not-yet-five Canadian-American daughter in the local Dutch kindergarten, hopeful she would pick up the language quickly. Everything was a challenge for her. She was still so little we often took her out of class early for a nap. She was still so little she struggled to get her shoes on the right feet. She was still so little pictures meant more to her than reasons.

So of course she was completely baffled when I told her she couldn’t make any more Zwarte Pieten out of black construction paper. ‘How could the school not warn us?’ I railed over dinner that night. ‘Do parents not get the choice to opt out of this?’

And then the Zwarte Pieten were everywhere: in the windows of the cake shop on the corner, their colourful suits deranged and cheerful; on the walls of my son’s day-care where infants stared up at them absently, their unfocused eyes drawn to the contrast of black faces against white walls; and finally, gallivanting through city centre by the hundreds, their white skin painted black as black.

With every painted Piet we saw, I felt like I had to remind my kids: this isn’t okay for you. Would they believe otherwise if I failed to speak up? But Zwarte Piet was around every corner. I got tired of the sound of my own voice straining for ways to talk about something so tricky with people so small. I got tired of taking the fun out everything. We resolved to just leave town the next year.

Something was off

Then one day my daughter came home with news: she had been moved next to one of her Dutch friends in class. He’s black. But something was off; she was worried. ‘I’m nervous, mama. What if he plays tricks on me?’

And there it was: all my talking, preaching, teaching – undone by the power of a picture and a story. Her teacher assured me that for the kids, Zwarte Piet was not about race. But without any help from an adult, my daughter’s young mind had made the very short leap from a black construction paper face to the only other black face in the room.

I tried again. ‘Hey. You know how all the kids tease you because you don’t understand much Dutch? And you feel so different?’

‘Yes, I hate it.’

‘How do you think your friend feels when kids think he is a Zwarte Piet just because he has dark skin?’ The question felt hopeless after so many futile attempts, but something must have landed. The next day she told me the two had played together all afternoon.

It was all undone by the power of a picture and a story

We aren’t leaving town this Sinterklaas season, after all. Groningen is home now and it’s where we want to be. But we are prepared for the inevitable conversations the holiday will require from us as buitenlander parents. This year my kids already know: we make rainbow Piets at school. But my daughter is a little worried about having one more reason to seem different.

On a recent walk to the grocery store she pointed out the reappearance of the Zwarte Piet dolls in the window of our local cake shop. ‘Why do we just keep making Zwarte Pieten?’ she sighed.

We decide

We stopped to consider the dark faces, the huge lips, the afros, the gold jewelry. I stopped to consider how much more a not-quite-six-year-old understands than a not-quite-five-year-old.

‘Well’, I said, ‘he’s a character in a story that people love. Telling stories is what we do; we make up beautiful things to remember who we are, or who we would like to be. And we pass them down to our kids, and our kid’s kids. And once a year we all conspire to pretend the stories are true. We set out shoes and we dress up in costumes and we exchange gifts and we try to bring something to life that makes the season feel warm and happy and set apart.’

She nodded along. This part was easy to get; no one is more willing to suspend disbelief for the sake of a little magic than a five-year-old.

‘You know, it’s really hard to change a story you love, because it feels like changing who you are. But the thing is, kiddo, those stories belong to us – we get to decide how they go. So what if one day you realise that a part of the story you thought was beautiful is actually kind of ugly?’

She didn’t skip a beat. ‘You just tell a better story.’