Fraudulent findings

When archeologists lie

It’s a good thing that archaeologist Marcel Niekus has such an amazing eye for detail. It’s also good that he has an almost photographic memory of every flint artefact he ever touched. Years after he has held an arrowhead, a blade, or a celt, he can still remember exactly what it looks like. He knows where the shavings were struck off, the exact curve of the percussion bulb, the patina shine of the stone.

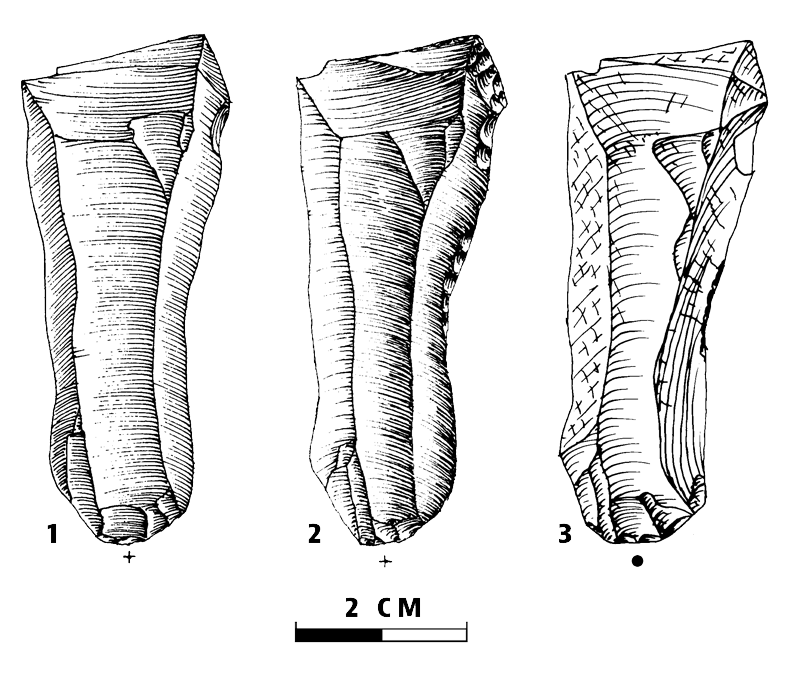

So in 2002, when he was checking the literature about the Ahrensburg culture in the Netherlands – the last reindeer hunters to pass through Europe until approximately 9,000 BC – he noticed something. A drawing of a blade that had been ‘found’ on the Ginkel Heath and written about in the eighties bore a remarkable resemblance to a drawing he had made of a blade that was supposedly discovered in the Frisian village of Sintjohannesga. He had studied the same object eight years ago.

Suspicious

Niekus went through his notes from eight years ago, and voila! The flint tool, which well-known amateur archaeologist Ad Wouters had donated to the Fries Museum, had already been ‘found’ somewhere else and described in detail -by Ad Wouters himself. ‘No single flint has the same pattern’, Niekus explains. ‘The shape, the flake scars, they’re all completely unique.’

It was suspicious.

Was Niekus surprised about the deception? Not really. Wouters was well-known for passionately defending a fraudulent amateur archaeologist, Tjerk Vermaning, both as a witness in his court case in 1975 and also in the book J’accuse in 1999. All the same, Wouters also had a good reputation and enjoyed international fame. ‘But I could take my drawing, which I’d done in pencil on transparent paper, put it on the published ink drawing, and see that it was a perfect match.’ But that’s all he had: a single drawing.

That is, until he was asked to contribute to a Festschrift to honour a colleague’s retirement who used to manage an archaeological warehouse in Nuis. The warehouse contained the blade from Sintjohannesga as well as other artefacts supposedly from the same location; Wouters had donated them all to the Fries Museum in the nineties. The warehouse also held a particularly special bruised blade, also from Sintjohannesga: large, with clear markings. Its origin was not suspicious. Wouters had never claimed the bruised blade.

Bruised blade

Niekus decided to look into it. He went to work, with help from retired archaeologist Dick Stapert and his wife Lykke Johansen. There was nothing wrong with the bruised blade: it was clearly a great find. But the other artefacts that Wouters had donated weren’t, and it soon became clear that the Sintjohannesga blade wasn’t the only object with a suspicious origin story.

A projectile point that Wouters had donated to the Fries Museum had been discovered twice: once at the Ginkel Heath and at Vessem 12, an then later archaeological site near the North Brabant village of Vessem. One scraper was stamped with the barely legible code ‘EV’, which after some investigation turned out to stand for ‘Ede V’ – another link to the Ginkel Heath. And a point from the Ahrensburg culture, which had been discovered at the Havelter hill, had also been discovered, earlier, at the Ginkel Heath. All of these artefacts were connected to Ad Wouters. ‘We don’t even know if the Ginkel Heath even contained any artefacts’, says Niekus. ‘Probably not.’

Reindeer hunters

As he found out more about Wouters, a pattern emerged: a modus operandi. The archaeologists who first discovered the artefacts were either dead, untraceable, or never existed. Wouter claimed that Frisian archaeologist Minnema was responsible for the ‘findings’ from Sintjohannesga, and that Minnema had, in turn, passed them to him. But because Minnema died before Wouters donated the findings, his claims about their origins were unverifiable. Another interesting, overlooked detail: the flint the objects were fashioned from came from all over the place. Would reindeer hunters from Sintjohannesga go all the way to South Limburg to get flint? ‘That too is highly unlikely.’

Wouters published an article about a hand axe which he claimed an amateur had found on the island of Vlieland. But when questioned, the amateur in question said he had never laid eyes on the axe. Wouters also added his own artefacts to objects other people had found. ‘This would increase the value of archaeological sites’, says Niekus.

Archaeological site forgery like this has a serious impact, he says. Without a point of origin, artefacts are scientifically useless. Whenever possible, the exact coordinates and the stratum an object has been found in should also be recorded. But these blades and scrapers? ‘We don’t know anything about them – they’re useless.’

And that means that all the findings that involve Wouters – who died in 2001 – should be re-examined, says Niekus. ‘We need a black book. All the findings whose origins cannot be independently confirmed should be removed.’

And that mean that all the findings that involve Wouters – who died in 2001 – should be re-examined, says Niekus. ‘We need a black book. All the findings whose origins cannot be independently confirmed should be removed.’

Iceberg

This doesn’t only concern the artefacts from the Ahrensburg culture, a fifth of which are now worthless. Niekus is convinced that they have only found the tip of the iceberg. After all, Wouters worked throughout the Netherlands since the fifties, rather than just in Drenthe like his friend Vermaning.

The question remains: why Wouters would do this? Tjerk Vermaning not only achieved fame with his spectacular findings, he also made quite a bit of money. But Wouters gave away all his findings.

Niekus speculates that Wouters’ situation is not unlike that of Diederik Stapel, who also enjoyed a great reputation and the renown of a great archaeologist. It’s possible he was just trying to keep up the ruse.

is still respected by many, even today. Niekus spoke to one of his followers, who has several of the Havelter Hill objects. ‘You’re seeing ghosts’, the man snapped at him, when he cautiously tried to explain that the collection might not be all what it has been said to be. ‘Of course some people aren’t happy’, says Niekus. ‘But we have to start cleaning up this mess.’

The Vermaning affair

In the sixties, Tjerk Vermaning shot to fame due to his spectacular finds of flint tools in Drenthe. His discoveries from the Middle Paleolithic – the time of Neanderthals – proved that Drenthe had been inhabited at least thirty to fifty thousand years earlier than previously believed. The Drents Museum bought his findings for 10,000 guilders, he was given a financial grant to support his work, and he was awarded the Drenthe Cultural Prize in 1966.

Researchers Harm Tjalling Waterbolk and Dick Stapert at the RUG’s Biological Archaeological Institute, however, doubted the findings’ authenticity. They believed that Vermaning had created them himself and put them in the ground. This led to a controversial court case in 1975; Vermaning was accused of fraud. The case caused a great commotion, with amateur archaeologists and RUG archaeologists on either side of the battle. And although Vermaning was cleared of charges due to a lack of evidence, his artefacts are considered forgeries to this day.

Later, people wondered whether Vermaning was actually the evil genius behind the forgeries, or if he himself had been manipulated. In his book about the affair, Scherpe stenen op mijn pad, Waterbolk imagined different possible scenarios. In one, Ad Wouters collaborates with Vermaning and was in fact responsible for creating the artefacts himself.

The book infuriated amateur archaeologists, who still insist that both Vermaning and Wouters are innocent