waybackmachine

The old HortusA botanical oasis became an enclosed garden

Can you imagine? Along the route that students walk from the Heymans building to the Bouman building used to be a lush garden. Sure, it’s still a garden, and students and staff love it, but it’s just not the same…

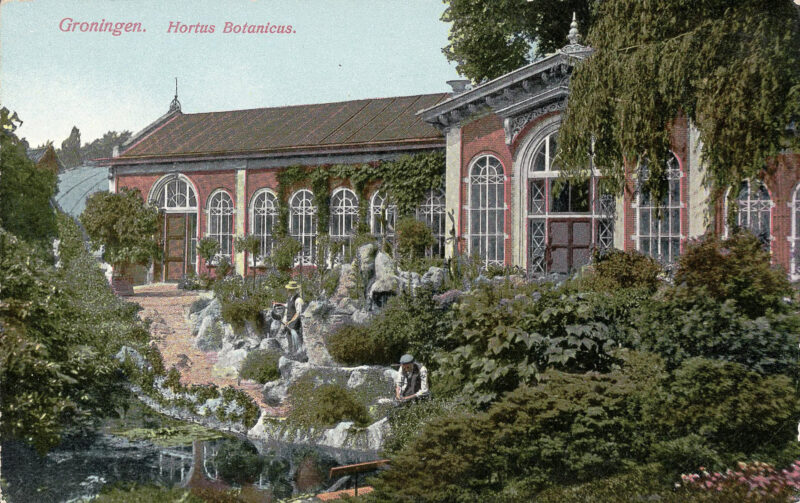

This photo was taken somewhere between 1900 and 1915, when the enclosed garden at the social sciences faculty was still called the Hortus Botanicus: the place where the university grew its plants. Initially, they mostly grew medicinal herbs that medical students would learn to recognise. Later, when the focus shifted to botany itself, they added many other plants.

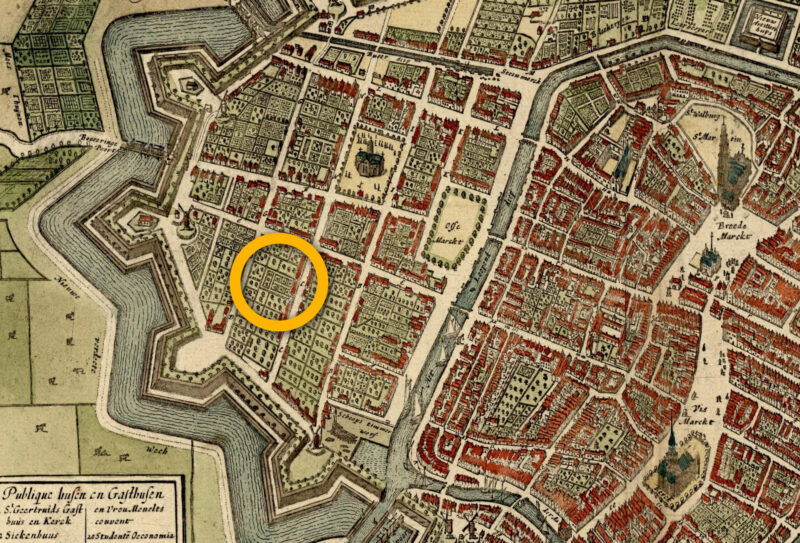

Approximately four hundred years ago, this was Groningen pharmacist Hendrik Munting’s ‘backyard’. Munting was very well travelled, and he’d learned a lot about botany during his trips: he’d even studied with the man who took care of pope Paul V’s medication! He returned to Groningen in 1626 and bought a plot of land in the Rozenstraat. Over the next few years, he kept adding bits of rented land.

Munting was also a tulip trader at a time where a single bulb would sometimes cost more than a canal house in Amsterdam. When that market collapsed, Munting had to find a different way to make money. He asked the province if he would be allowed to teach botany classes. He would allow the students access to his garden so they’d be able to study more than two thousand plants, rare rocks, animal specimens, and shells he’d collected.

Succession

In 1656, Munting was even allowed to build a greenhouse: the orangery. Since it was located on his land, the university had no choice but to have his son Abraham succeed him as professor of botany when Hendrik died two years later. When Abraham died in 1683, his son Albert succeeded him in turn.

When Albert put the house and the garden up for sale due to financial woes in 1690, the province seized the opportunity. The Hortus Botanicus became the property of the province in 1691 and the university was officially in charge. After that, no more Muntings were hired.

This is the orangery in the old Hortus. It differs from the similarly named dining facilities at the Grote Rozenstraat. The first ‘orangery’, a greenhouse, stood where the Heymands and Munting buildings are now.

Deteriation

Once the Muntings had left, the garden deteriorated. Regular people would put their own plants in the warm greenhouse, which meant the university’s plants didn’t fare too well. Then there were the professors who nearly killed precious trees by lopping off branches they wanted to use ‘for weddings’ and other special occasions. No wonder German tourists called the garden ‘bare’ in 1710.

The orangery in this picture stems from 1863. It was built after the previous orangery was close to collapsing: ‘its façade was leaning forward, there were tears in the brickwork, its window frames were rotted through, and the beams in the walls had to be supported by pillars to prevent the building from falling down’.

There was no other choice than to build a new orangery.

You probably recognise this bit. It wasn’t added to the Hortus until 1838. Famous agricultural researcher Van Hall created an ‘economical’ garden for the study of agricultural crops and fruit trees. The little experimental gardens where famous botanist Tine Tammes cultivated her plants were added later, with the lily pond in the middle.

The rest of the garden was redesigned into how it looks in top photo in 1910: it became a garden people could walk in, with winding paths that remain to this day. On top of that, the general public was allowed to visit the garden a few days a week.

Surely a beautiful old garden in the middle of the city would be something the university would be keen to preserve. Alas, after the war, the university was bursting at the seams and in desperate need of places to put students and researchers.

The university has purchased Huis de Wolff in 1918 with the intention of creating a new Hortus with enough space. However, nothing had happened since then. But this was all about to change. The Hortus was moved to Haren and the Orangery was torn down to make way for the Alpha building, so named because it housed the language programmes.

Surely a beautiful old garden in the middle of the city would be something the university would be keen to preserve. Alas, after the war, the university was bursting at the seams and in desperate need of places to put students and researchers.

The university has purchased Huis de Wolff in 1918 with the intention of creating a new Hortus with enough space. However, nothing had happened since then. But this was all about to change. The Hortus was moved to Haren and the Orangery was torn down to make way for the Alpha building, so named because it housed the language programmes.

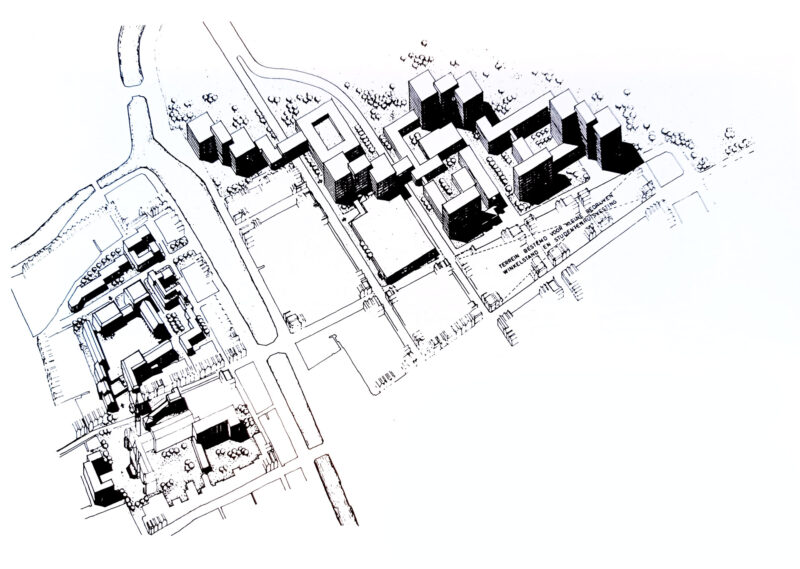

The Hortus neighbourhood actually came close to being completely torn down and replaced with university buildings. The city had plans to build wide ring roads around the city centre, and one of them would bisect the Hortus neighbourhood. In the meantime, the university had bought up dozens of derelict houses and planned to build a complex that would stretch from the Noorderplantsoen to the Noorderbinnensingel, with aerial bridges where people could cross the main roads. After the neighbourhood residents protested, the plan called off around 1975.

Diggers

Finally, some peace and quiet. Or not. In the nineties, the university once again had plans to start building. This time, the Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences. Three building blocks in the Hortus garden would create six thousand square metres of space. Residents were furious and started suing, taking it all the way to the Council of State. Not only were they protesting the high buildings, they also wanted to keep the monumental gardens. When the university wanted to tear down the little half-timer house next to the Bouman building, they even formed a human shield to stop the diggers.

There was so much trouble for nearly ten years, that the university had to withdraw most plans and return to the drawing board.

The final result is what we can see today: the Munting and Gadourek buildings, but most importantly, the large glass wall in the Nieuwe Kijk in ‘t Jatstraat through which the monumental weeping beech tree is visible to everyone in the neighbourhood.

Sources used for this article: Klaas van Berkel, Universiteit van het Noorden, parts I, II and III (Groningen 2014, 2017, 2022) | Ch. Henriëtte Andreas, In en om de Botanische Tuin, Hortus Groninganus 1626-1966 (Groningen 1976) | M. van Klinken, Plannen, stagnatie en nieuw elan. De universiteit en de Hortusbuurt in de tweede helft van de twintigste eeuw (Groningen 1996) | Ben Hofman, Niewe Stadt, 400 jaar Hortusbuurt Ebbingekwartier (Groningen 2020).