'My parents are sacrificing a lot'

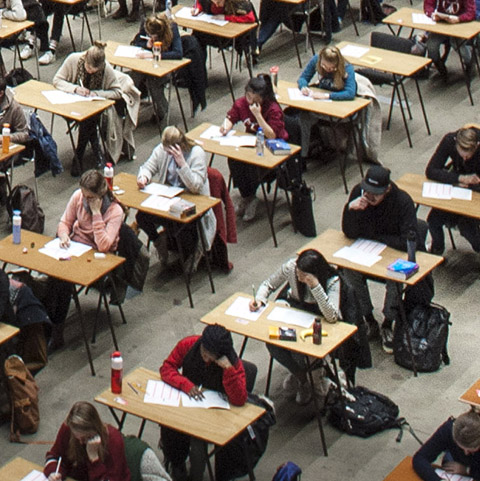

Internationals feel pressure to perform

It’s remarkable, according to psychological counsellor Rike Vieten with the Student Service Centre: there are almost as many international as Dutch students who request an intake interview. ‘In 2019, there were a thousand requests from internationals, and 1,300 from Dutch students’, she says. Interestingly enough, there are approximately seven thousand internationals in Groningen, as opposed to 25,000 Dutch students.

The international requests are from both EU and non-EU students, but Vieten has noticed that it’s mainly students from outside the EU who find themselves struggling. ‘Factors like high tuition fees, parents’ expectations, the visa requirements, and climate and cultural differences all play a role. The people who come to us for help often suffer from a combination of issues.’

Every student has problems sometimes. Vieten says that it’s essential to have a network you can count on. ‘But that stability falls away when you move somewhere else.’ She doesn’t have a quick fix, but she can give students a bit of advice: ‘Share your story with the people around you, try to find the balance between your own culture and local customs, and prepare for the differences in the educational and health care system if you’re moving to a different country.’

UKrant spoke to four UG students from outside the EU. What issues have they encountered in Groningen, and is the pressure to do well really that high?

The Student Service Centre has workshops, courses, and personal guidance for students who are struggling with psychological, financial, or legal issues, are handicapped, or want to improve their study skills.

Vladyslava Panasovska (22), pre-master in European economic law, Ukraine

EU students don’t have to pay all that much to study in the Netherlands, but people from outside the EU, like Vladyslava, have to hand over a lot more money. When she’d finished her bachelor in international & European law at The Hague University of Applied Sciences, she came to Groningen for a pre-master in European economic law. ‘Fortunately, they only charge the legal tuition fees for a pre-master, but the master will cost me fifteen thousand euros next year.’

‘My parents are sacrificing so much to pay for this’, says Vladyslava. ‘We’re saving up together. We came up with a budget strategy, but that means we won’t be going on holiday this year.’

I want to make a change in Ukraine

Vladyslava is grateful to her parents. ‘But sometimes I feel guilty as well. I feel like I have a moral duty to do well. My parents would never say that, it’s just how I feel.’

She’s also motivated by the war in Ukraine, which broke out in 2014 and is still going on. ‘My hometown was occupied by pro-Russion forces’, says Vladyslava. ‘I’d just graduated high school, but the ceremony was cancelled. We were forced to move to Kiev.’

The incident made her ambitious. ‘I want to make a change in Ukraine. I want to help my country with what I’m learning in my studies. That’s also why I’m volunteering at the Ukrainian embassy in The Hague.’

Vladyslava went back to Ukraine when the coronavirus hit the Netherlands. She misses the university’s atmosphere, community and facilities that used to motivate her and has struggled to finish the pre-master. She’s afraid that she’ll have to pay the tuiton fee for non-EU students for an online master’s programme.

Zafar Jon Niyazov (22), master in chemical engineering, Uzbekistan

Studying abroad is not an opportunity that many Uzbeks get, so Zafar knows how privileged he is. ‘The difference between the rich and the poor in Uzbekistan is vast’, he explains. ‘I’m only here because my parents had the opportunity to work in Denmark. It adds a little extra weight to my education, knowing that my friends in Uzbekistan don’t get this opportunity.’

He’s grateful to be doing his master in chemical engineering in Groningen after finishing his bachelor in chemistry, but he also feels the pressure. ‘My family put a lot of work into getting me here, so I have to live up to that expectation. I can’t just take a gap year. I’m here to study and I have to work hard.’

My friends in Uzbekistan don’t have this opportunity

Zafar knows that an Uzbek applying for a job in Europe will probably be less attractive to employers than an EU citizen with similar qualifications. ‘I’m also working on my soft skills, like communication and frankness. I’m teaching myself by striking up a conversation with a stranger every single day. I think it will help me compensate for the other aspects.’

In Groningen, he mainly struggles with the segregation between Dutch students and internationals. ‘People with the same cultural background seek each other out’, says Zafar. He can see it happening during lecture breaks, but elsewhere as well, like when he was looking for a room. ‘Every single ad said they didn’t want internationals. That’s a bummer, but I can’t really blame them. It’s in our nature to want to be with like-minded people.’

Zafar is back with his family in Uzbekistan, but he’ll be back in September. He expects his second year will be a challenge, because of the restrictions to lab work and real-life classes. He tries to ignore the news about Covid-19 as much as possible, so he doesn’t get stressed.

Yoga Wang Mahendra Alam (24) and Rakka Deaprilando Malik (22), bachelor in international business, Indonesia

Yoga and Rakka were studying management economics in Indonesia when they were presented with an interesting opportunity to finish the second half of their bachelor programme in Groningen, in the international business department. They’ll be receiving two degrees: one from the UG and one from their Indonesian university.

But once they arrived here, they realised things were very different on the other side of the world. Both say the pressure to work hard is much higher in Groningen. ‘The way we’re supposed to study is fundamentally different as well. In Indonesia, we mainly used textbooks, but here we have to read a lot of academic articles’, says Rakka. ‘Exams are also different from the way they are at home. Here, they’re using actual cases that are difficult to solve. That took a lot of getting used to.’

The ECTS requirement was hanging over me like a dark cloud

As if that wasn’t enough, they ran into another stressor that most European students don’t know about: non-EU students in the Netherlands receive a residence permit from the government. One requirement of this permit is that students get at least thirty ECTS each academic year.

A depression prevented Yoga from getting those points last year. ‘While I was struggling to make it through my courses, this regulation was hanging over me like a dark cloud’, he says. ‘Added to that was the stress I felt from Indonesia. Graduating university isn’t an achievement, but a milestone you absolutely have to reach. That can weigh heavily on you if you’re not feeling well.’ Thanks to support from his study adviser, he was able to stay.

Yoga and Rakka are taking a little longer to finish their degree, but they certainly don’t regret their adventure. ‘I’ve changed in such a positive way’, says Yoga. ‘I had to go through this to come out stronger on the other end. Coming to Groningen was the best decision I ever made.’

Yoga is still in Groningen. He’s doing well. The corona measures have given him more freedom to study. Yoga’s still happy with his decision to come to the Netherlands. Rakka hasn’t replied yet to our request for an update.