waybackmachine

The Physics Lab Ironless experimenting at the Westersingel

See the tram wires at the top of the photo? They caused a lot of trouble for one of the most modern laboratories Groningen had ever seen: a building constructed with practically no iron, allowing physics professor Herman Haga to study the Earth’s magnetic field.

Nails, studs, pipes; they were all made of copper to ensure nothing would mess with Haga’s readings. And so, just for a little while, Groningen had the most modern physics lab in the world.

Haga started campaigning for a better lab the moment he arrived in Groningen in 1886. He immediately realised that the rooms in the old Academy building weren’t up to par for his work.

Whenever students walked past, or when it was particularly windy, the wooden floor would vibrate so much that it disrupted his readings. But when he moved to the basement, his readings were affected by the caretaker’s pump handle, since he lived in the basement.

Things needed to change, and this led to the construction of a hypermodern new building on the corner of the Westersingel and what’s now the Kraneweg, in 1892. The vibration issue was solved by building on top of the old Cranedwinger bulwark, which meant the ground was settled and even. Because there was no iron anywhere in the building, Haga was able to do cutting-edge research.

This made it all the more frustrating when the city of Groningen decided it didn’t care about any of that and build tram rails on the Kraneweg. The electric cables were underground, which meant that experiments could only be done at night.

As modern as the building had initially been, twenty years later, it was already outdated. The number of students had increased, as had the number of professors. In 1927, two extra storeys were added on top of the building, and the inside was renovated, as well. The new build did use iron; since research into x-rays was now the latest thing, the metal was no longer an issue.

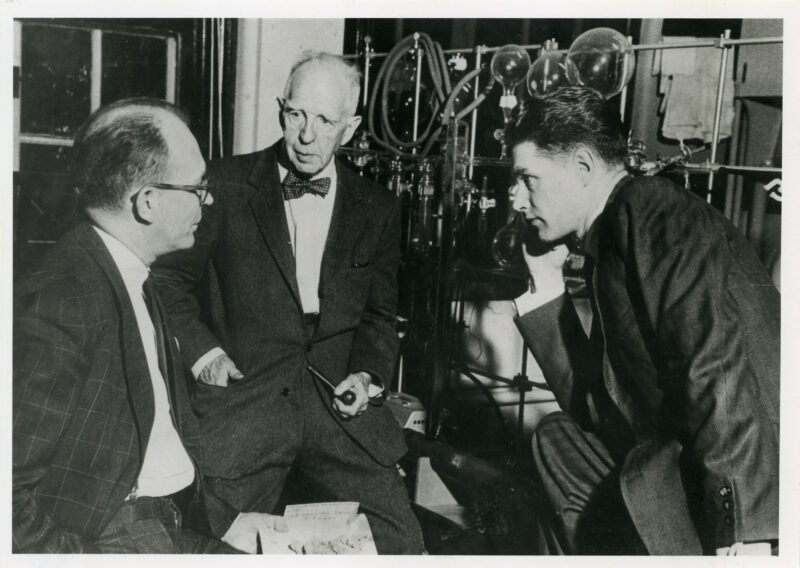

Frits Zernike, the man who would win a Nobel Prize in 1953 for inventing the phase contrast microscope that revealed living transparent cells, also got his own space. His laboratory was separate from the rest of the building and was outfitted with a double concrete floor to prevent the traffic passing by on the Westersingel from disrupting his research.

The next renovation took place in 1962. The teaching labs were increased in size, laboratories for optics research were added, and Zernike’s department of theoretical physics was expanded. A tower was added to house the Van de Graaff generator: a particle accelerator used for nuclear physics research.

Famous physicist Hessel de Vries was given a lab that featured a thirty-metre deep well so he could perform his ground-breaking research into carbon-dating. In 1949, American scientist William Libby had discovered that the amount of radioactive C14 in the atmosphere could be used to date archaeological finds made of wood, among other materials. But it was De Vries who realised that this amount wasn’t stable across the year, and he also refined the measurement methods so they could be used in practice.

This research probably would have led to a Nobel Prize in 1960, but a private tragedy prevented this. Spurned by his secretary, he murdered her in 1959, after which he took his own life.

The Physics Laboratory was in use until the nineties, after which the Noorderpoortcollege took over. By that time, it was in a terrible state. The building had been renovated so many times that there was almost nothing left of the original structure. Noorderpoort decided to strip the interior and start anew; they built a gymnasium behind the large stained-glass window of a classroom.

Sources used for this article: Klaas van Berkel, Universiteit van het Noorden, parts II and II (Groningen 2017, 2022) | Noble Science E-gids (Groningen 2017) | StaatinGroningen.nl