waybackmachine

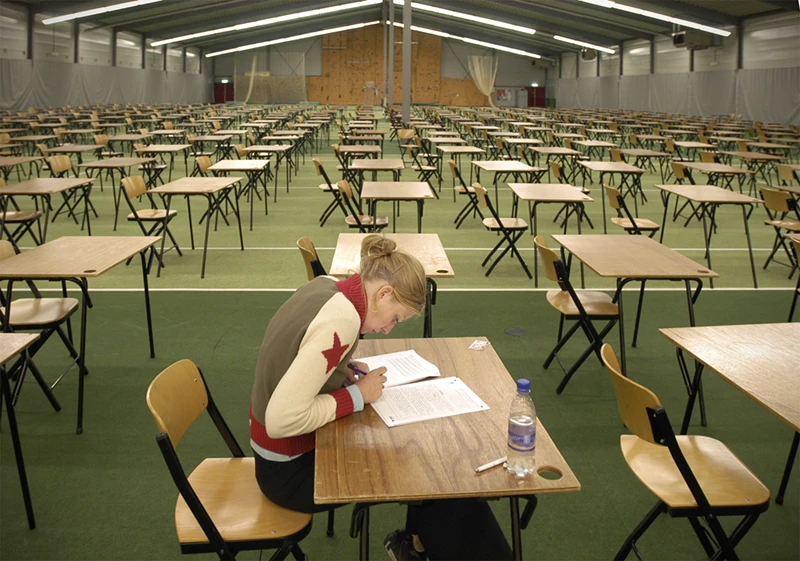

Sports centre ACLOThe academic welfare state

In the sixties, the vast green fields were still called Paddepoel Noord: flat lands stretching from the Reitdiep to the horizon, where the wind could do as it pleased. That is, until the UG built its large WSN building (which was later renamed the Duisenberg building) and, all the way in the south western corner, the Academic Centre for Physical Education, these days more commonly known as the ACLO.

In January 1990, the campus was named after Groningen Nobel Prize winner Frits Zernike. The campus has been under construction one way or another since then. In 2023, the lands have largely disappeared, and the campus houses more than four thousand employees and approximately 35,000 students from both the UG and the Hanze University of Applied Sciences, as well as laboratories, educational facilities, high-tech buildings, and approximately 150 businesses.

After several locations all over town, the ACLO opened its final doors in September 1967 at University complex De Paddepoel, as it was then known. It was a modern and contemporary sports centre comprising a sports hall, three smaller venues, and fields and courts, mainly for football and tennis.

Today, approximately twenty thousand UG and Hanze staff and students use the sports facilities. But the Hanze hasn’t always been welcome. Two years after the sports centre opened, applied sciences students were allowed to use it, as well. Three years later, however, they were asked to leave again, as the minister felt the subsidies only applied to the research university.

Sports and sex

The centre was being built during the time of flower power and massive student protests, against the Vietnam war and in favour of free sex. But it is perhaps not as well known that this was also the time that sports became increasingly popular and accessible.

This development wasn’t as obvious as it might seem. Until the second half of the twentieth century, exercising was seen as a privilege for those who were well off. At the university, this meant the student associations and their wealthy members. The ACLO changes this. Anyone who didn’t belong to a student association suddenly had affordable access to exercise.

The numbers speak volumes. When the centre opened in 1967, it already boasted thirty different sports associations and six thousand members, which was around half the total student population at the time. In fact, Groningen was the sportiest student city in all of the Netherlands.

UG historian Klaas van Berkel, who wrote three volumes on the university of the north, aptly describes the ACLO as ‘the oldest part of the academic welfare state’.

Forerunner

The initiator of this ‘welfare state’ was Frits Buytendijk (1877-1974), a versatile and flamboyant professor who taught general physiology in Groningen. He was one of the forerunners of sports medical research – something completely new at the time.

He managed to convince the International Olympic Committee to set up a laboratory for this type of research, where Buytendijk and fifty international scientists started work in 1928, the year the Olympics were held in Amsterdam.

Buytendijk had long been convinced that exercise was good for a person’s health, but at the time, very little was known about it, and some people even openly doubted it or warned people about ‘those foolish sports’. But the professor saw all its advantages: exercise is relaxing, brings people together, makes them feel like they belong somewhere. There was one argument the university liked in particular: exercise made people better students.

After the war, the university was growing rapidly, and with it grew the number of students looking for a place to exercise. The University Sports Centre at the Antonius Deusinglaan, the current UMCG complex, had grown too small and was falling into decay. The little sports field belonging to the centre had also disappeared, according to a sad note in the 1959 annual report.

Cry for help

Other student exercise areas were also in poor condition. Many a time, matches had to be cancelled because ‘the fields were completely unsuitable for use’. In spite of all the cries for help, this continued for years.

Because of that, sports associations had to stop letting in members, training sessions were cancelled, a fledgling club didn’t make it because there was no accommodation, and people weren’t allowed to swim for more than an hour.

Fortunately, the solution came a few years later, in 1967. After that, the sports centre grew steadily. While some associations never joined ACLO, such as the rowers at Gyas and the Donar basketball players, many others did find their home there, ranging from gliding planes to football, from horse dressage to padel, and fitness to ice skating.

Applied sciences students

After a debate that had lasted more than ten years, the ACLO finally started accepting students from the university of applied sciences as well. Not that their motives were particularly pure: the politicians in The Hague were cutting funds which threatened to eradicate student sports altogether if the university didn’t allow this ‘merger’.

That is why today, sixty (former) UG and Hanze athletes’ photos adorn the Olympic Wall in the sports centre, as both a tribute and a showcase of student sports.

Would the Dutch volleyball players have become champions at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta without the guidance of their coach Joop Alberda, who started out his athletic career at University Complex De Paddepoel?

Would gymnast Epke ‘The Flying Dutchman’ Zonderland have become the king of the horizontal bars at the 2012 London Olympics without professor Frits Buytendijk? Would short-track skater Xandra Velzeboer have won Olympic gold in Beijing last year if that desolate little corner in Paddepoel Noord had never been converted?

Sources for this article include ‘Sportcentrum Illustrated’, the magazine created for the sports centre’s fiftieth anniversary in 2017, and part 3 of ‘Universiteit van het Noorden’, by UG historian Klaas van Berkel.