Maruf Dhali and the power of AI

Unlocking the Dead Sea scrolls

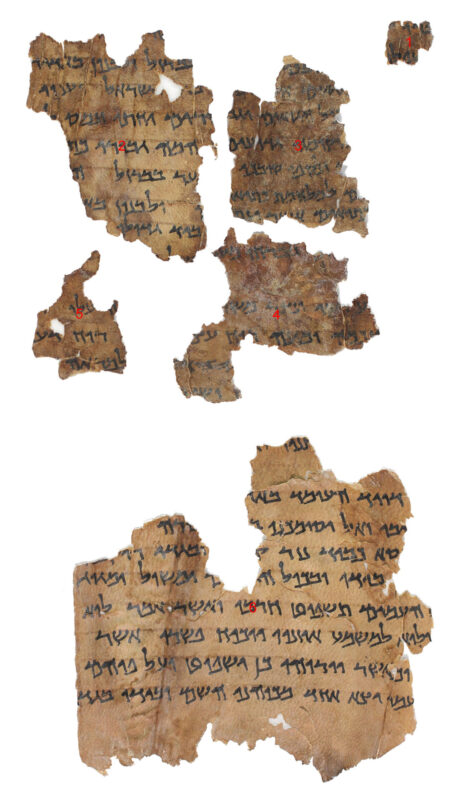

‘It is one of the biggest and most significant findings of manuscripts in the past hundred years’, Maruf Dhali says of the hundreds of scrolls that were found in eleven caves near Jericho between 1947 and 1956. The artefacts, mostly made of parchment and inscribed with texts from the Hebrew Bible, tell of historical events, but it’s not always clear who wrote about them, or even in which order those events happened.

In 2021, over two thousand years after the scrolls were inscribed, associate professor of AI and machine learning Dhali managed to find an answer to one long-unanswered question about the so-called Isaiah scroll. Was it written by one person, or were there perhaps multiple scribes?

It may sound unimportant, but evidence for or against a multiple-scribe theory could tell us more about society two thousand years ago. ‘You can link this with all kinds of other data and tell if persons were travelling from one place to another to contribute to the book, for example’, says Dhali.

AI model

Researchers were never able to find proof one way or another. ‘Because the handwriting for the whole book is so uniform, you can’t see any difference with the human eye’, Dhali explains. ‘And the differences in writing are so small that you need to compare a lot of data.’

You can’t see any difference in handwriting with the human eye

A specially trained AI model – put together by Dhali over two years – can do just that, although it still involves some human input. ‘Experts train the model by indicating which part of the roll contains the ink of the text, and which part consists of the blank page.’ The model can then compare each individual letter of the Hebrew alphabet from the 54 columns of the scroll.

Dhali and his team discovered that the Isaiah scroll had two scribes, with nearly identical handwriting. ‘The fact that they wrote very similarly suggests there was some kind of training going on’, says Dhali. ‘It shines a different light on their culture.’

Radiocarbon dating

Now he has moved on to the other Dead Sea Scrolls. Thousands of these are missing dates. ‘It means experts in some cases only have a vague idea of when these scrolls were written, and when the events described took place’, Dhali says. ‘It’s very subjective. It’s like in your childhood, when you say “I got hurt when I was five years old”, and then your mom comes in and says “No, it was when you were six years old.”’

The model’s date range is better than the subjective look of the experts

To date the scrolls and end the uncertainty, Dhali relies on a scientific technique called radiocarbon dating, in which he measures the amount of radioactive carbon present in a sample. This says something about the age of the object.

In order to do this, colleagues of Dhali at the UG isotope department have to burn the sample. ‘Of course we don’t want to burn the whole scroll’, he says. ‘Luckily they only need a very small part of the sample, only a few milligrammes.’

But thanks to AI, he doesn’t need to date all of the scrolls that way. ‘As a starting point, we would only need to measure about thirty documents.’ With the information from this, an AI model called Enoch can calculate the age for related documents from the periods in between those carbon-dated manuscripts, by looking at the handwriting, for example.

Earlier date

It’s a model that Dhali and his colleagues have been working on for almost four years. ‘We finished the article explaining this model in 2022, but it’s still under review because it was such a big and complex article’, he says. ‘There are many expert fields related to the model. We did chemical analysis for the radiocarbon dating, there are physics involved, archeology, artificial intelligence for the model, mathematics, and religion.’

The model doesn’t give an exact date, but rather a date range during which the scrolls could have been made. ‘But it’s better than the subjective look of the experts trying to date a scroll’, Dhali says.

As it turned out, in virtually all cases the radiocarbon dating on the scrolls indicated an earlier date than the experts in the field thought. ‘The experts relate one event to another’, Dhali says. ‘So if your initial assumption for one event was that it happened later, then you would put every other related event later as well.’

It would take years if people had to read all these documents

Dhali was even able to solve another mystery surrounding the Isaiah scroll using radiocarbon dating. ‘We had already shown that the scroll featured two different handwritings, but some people still argued it might be one scribe who wrote at two different times, for example with a fifty-year gap during which he could have gotten injured, so his handwriting could have changed over time.’

It might sound convincing, but Dhali’s dating technique showed otherwise. ‘Our model says that even though the handwritings are different, they’re written at the same time’, he says. ‘The pieces of the scroll were just as old.’

Searchable archives

For another project, he’s working with the municipality of Groningen and several Dutch archives to make old documents searchable. ‘They have documents from the 1700s or 1800s that are interesting from a historical perspective, but they have no labels to indicate what they’re about, like a particular family or area. They could be registers, documents from tax authorities around that time or fines, for example. But currently, we cannot do much with them.’

Ideally, he says, they could be searched by an AI system. ‘It would take years if people had to read all these documents, even those from the municipality alone’, says Dhali.

But using AI for this is not an option at the moment, so he hopes to turn it into a citizen science project. People will be able to join the project somewhere next year. ‘We’ll ask them to indicate which part of the document contains a date, which part contains the main text, and which part contains the added remarks, for example’, Dhali says. ‘Those are things that even a kid could do easily. But with AI, it just ends up a mess.’

That doesn’t mean that an AI cannot learn how to do these tasks. ‘We’ll continuously feed this system the documents that citizens have labeled, in the hope that we can train it.’

Dhali is optimistic this will work. ‘Generally, if you have at least a hundred documents that are labeled like this, it’s a good start. That’s already quite a robust system that could recognise the different labels.’ From there, he says, you can keep on improving it. ‘There is no end to perfection.’