Ranko Gacesa dissects the microbiome

Tinkering with gut bacteria

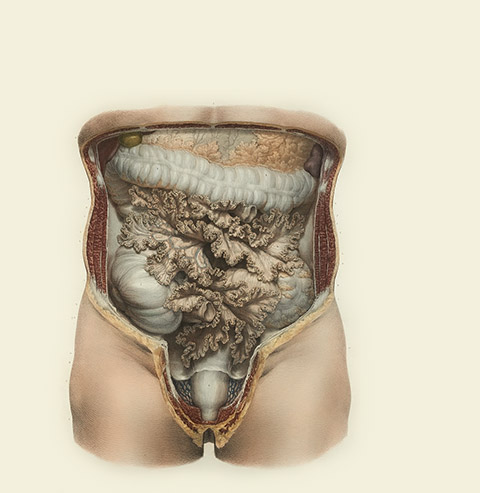

You probably don’t realise it, but your intestines form a complete ecosystem. Everyone has at least a hundred to six hundred different species of bacteria in their intestines; approximately a hundred trillion bacteria in total. That’s not an issue at all. In fact, without these bacteria, you’d have digestive issues, bowel movement issues, and most importantly, immune system issues.

This ecosystem is different in each person. Not just the number of bacteria is different, but so are the species. In fact, your gut flora has more in common with that of your roommates than that of your parents.

But how those gut flora, which are also known as a microbiome, work exactly is still a mystery. ‘Certain kinds of cancer treatments appear to work better depending on the gut flora, which means that if we could change the gut flora in a specific way, treatment might be more effective’, says researcher Ranko Gacesa.

Patterns

Gacesa’s research is part of the Dutch Microbiome Project, which was set up by UMCG researchers in 2015. The project’s goal is to catalogue the gut flora of more than eight thousand Dutch citizens. Gacesa uncovers patterns in large amounts of data. ‘I happen to be one of those people who’s good with computers’, he says.

Certain kinds of cancer treatments appear to work better depending on gut flora

Researchers collect stool samples from their test subjects. ‘A few clever tricks allow researchers to separate the gut flora bacteria’s DNA from the rest’, says Gacesa. Next, they read the DNA’s code. ‘What’s left is this kind smoothie’, says Gacesa, ‘a kind of mash of the DNA of all the different bacteria.’

Because he knows the genetic code of most of the bacteria he might find beforehand, the computer can then determine which bacteria will most likely be included in the smoothie.

Lifestyle

Gacesa also found out that the composition of a person’s gut flora isn’t genetic, which is what many people think. Extensive comparisons showed that the DNA smoothies of people who live together are more similar than those of related people. ‘It also turned out that the gut flora of brothers and sisters in a cohabiting family were more alike than those of their parents.’

That last one can probably be explained by the overlapping lifestyles brothers and sisters tend to have, especially when they’re similar ages. The large similarities in gut flora composition in people who live together is because we pick up bacteria from our environment and shed our ‘own’ bacteria. ‘Some studies even claim they’ve found similarities in the gut flora of people and their pets.’

That actually kind of makes sense. After all, a baby is born without gut flora; it only starts building up after birth. That means that the composition of your little intestinal ecosystem is largely determined by your environment.

Work together

So what happens when people move? Gacesa isn’t quite sure yet. His theory is that people’s ecosystems start to look less similar the longer they live apart, but he and his team are still collecting the data to study this further.

Some bacteria can become invasive species like those green parrots in the park

He also hopes to catalogue how all those different bacteria work together. ‘Just like animals and plants, the various bacteria in gut flora all fulfil a role in the intestinal ecosystem’, he says. ‘The general principles might roughly apply to everyone. That means that the different bacteria could fulfil the same role in different people.’

If we knew more about that, we’d be able to apply that knowledge and battle diseases with specific medication. One way this is already happening in broad lines is when someone’s intestines have been infected with the Clostridium difficile bacterium, which can cause severe inflammation. By transplanting someone else’s ‘poop smoothie’, you introduce other bacteria into the gut flora which essentially resets it, Gacesa explains.

Twenty years

It works, but we don’t know which exact bacteria cause this reset. That’s why Gacesa thinks it will take at least another twenty years before we’ll have invented pills with specific amounts of certain bacteria that will work on specific diseases.

It’s still very difficult to make any lasting changes to gut flora with short interventions. ‘The gut flora are very resistant to change, but some bacteria can become invasive species, like those green parrots you sometimes see in the park.’