The museum’s dilemma

What to do with the skulls

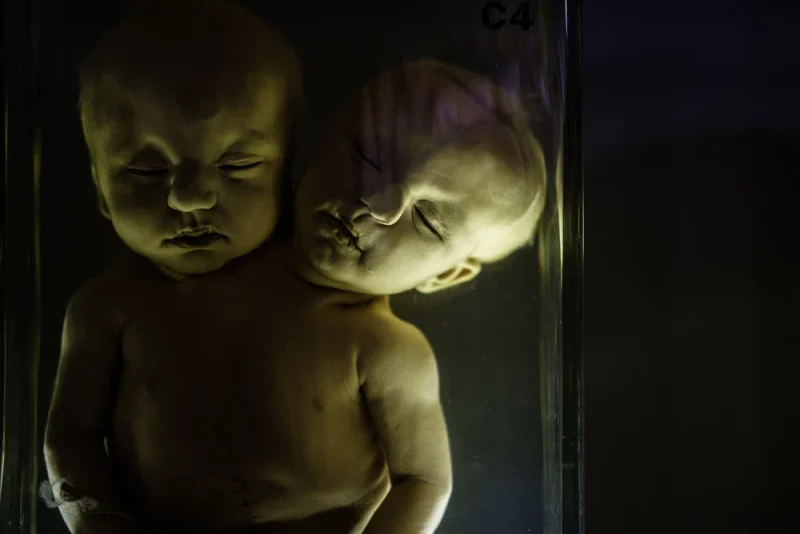

Cast in dim light are jars filled with body parts, floating in a clear liquid. The body of a man, cut into pieces length wise. A two-headed baby; a set of lungs, blackened by disease. Skeletons are lined up along the wall, ranging from tiny children’s frames to hunched-over human shapes that look like they could come alive at any moment. This is not a scene from a horror film, but a glimpse of the anatomical cabinet in the University Museum.

For most people, visiting this space is an interesting experience. Lars Hendrikman calls it the ‘wow factor’. But, says the director who joined the museum a little over a year ago, that’s not really the effect you want human remains to have on people.

Skulls

Many of the skulls at the University Museum are from Petrus Camper’s collection. He was a doctor, anatomist, physiologist, and anthropologist who collected skulls from all over the world, such as the ‘Hottentot’, or ‘resident of Madagascar’. He measured the exact ‘facial lines’ on these skulls to categorise the different types of human races.

He was an enlightened scientist who had an open view and eschewed the idea that any race was superior over another. At the same time, however, it’s clear that he often obtained the skulls without permission.

‘The question I ask myself is: can we still justify displaying human remains? And if so, what are the conditions under which we should display them?’

Hendrikman isn’t the only one asking these questions. The international museum community has been having an ethical discussion about the issue for a while, and this discussion has now reached Groningen. For the University Museum, it means that things will gradually be changing.

Tattooed skin

The University Museum owns several old tattoos. One from the late eighteenth century has been preserved by Pieter de Riemer. Another one is from Petrus Camper’s collection and belonged to an Italian sailor.

Tattoos became popular when James Cook went to Haiti in 1769. The word tattoo derives from the Haitian word ‘tattau’, which means ‘to tap’.

Initially, it was mainly sailors and mineworkers who adorned their bodies. The sailors often picked anchors, while the mineworkers had lamps tattooed, to serve almost as an amulet. Later, other symbols, like the wind rose, became popular. People were allowed to have the god Poseidon tattooed if they’d crossed the equator.

No permission

In order to understand why, it’s important to know where the various body parts, skulls, and skeletons in the museum’s collection come from.

Pretending the collection doesn’t exist is not a good solution

Some of them are skulls and specimens collected by the Groningen professor of medicine and anatomy Petrus Camper. They were given to the UG by royal decree in 1820. Another part of the collection used to belong to physician and anatomist Pieter de Riemer from The Hague. Then there are foetuses and babies in formaldehyde, or skeletons that were once used in medical education.

But over the course of years, much of the information about where these human remains came from has been lost. The providence of only a few is known, and there’s a very good chance that nobody ever gave permission for their remains to be displayed in a museum.

Deformed skeleton of a man with rickets

The ‘English disease’, or rickets, caused a lot of damage in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The lack of calcium and vitamin D, which the body produces under the influence of sunlight or absorbs from products such as fish oil, often led to serious skeletal deformities in children, especially in their spine and pelvis.

While the disease isn’t deadly, the consequences were severe. The back deformities caused people enormous pain. The museum is also in possession of the deformed pelvis of a woman from Warffum, who died because she couldn’t give birth to her baby.

Some of the remains were acquired during colonial times, which adds an extra layer to the discussion. Hendrikman suspects the debate on the ethics of displaying human remains in museums is partially informed by the larger discussion on colonial history. He realises that it’s a sensitive subject.

History

A final factor is that the function of the collections has changed over the past few years. At one time, their primary function was educational, to teach students how a foetus develops in utero, for instance, or what a pelvis deformed by the English disease looks like. These days, they’re mainly there to shed light on the history of the university.

Foetus in formaldehyde

This ‘pregnant uterus with hernia’ is an object about which very little is known. No one knows when this foetus died or who preserved it in formaldehyde. It was probably used for medical educational purposes. At a time when very few imaging techniques were used, body parts, including foetuses, in formaldehyde were essential to show students what happened in the human body.

But the question is whether visitors understand this. ‘The anatomical cabinet is really popular. It features in most of the social media posts on the University Museum’s interior’, says Hendrikman. While that’s good news in terms of visitor numbers, he fears most people are drawn in by the wow factor and less by an actual interest in history.

Is a fake skeleton less educational than a real one? No

‘It’s an interesting but difficult dilemma’, he says. ‘My intuition tells me we shouldn’t be displaying these human remains, but just closing the door on this collection and pretending it doesn’t exist is not the solution.’

After all, displaying the history of the university is one of the museum’s most important functions. ‘Petrus Camper’s skull collection has been a part of that history for more than two centuries’, says Hendrikman. ‘We have to figure out how to, on the one hand, do justice to the 21st-century insights into showing human remains and, on the other, the history of our own institute.’

Two-headed baby

The only thing that is known about this ‘two-headed miscarriage’ is that it belongs to the pathological collection. These Siamese twin would also have been used in medical education.

Putting body parts and miscarriages in formaldehyde became especially popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most body parts belonged to criminals, while the babies were often stillborn. Pieter de Riemer, an anatomist from The Hague, displayed his specimens in his own home. The University Museum came into possession of his collection in 1831. De Riemer would often give tours of his collection to interested parties.

Then there’s the educational value the collection represents. The museum organises tours for medical students, and these objects are used to explain what someone suffered from, how these kinds of diseases were treated at the time, and how hospitals treat patients today.

Balancing act

But Hendrikman can see another alternative, as well: ‘Are fake skeletons less educational than real human ones? The answer is probably no; they’re equally educational. The whole conundrum is a balancing act I’m currently trying to figure out.’

But he’s not on his own: he discusses the issue with his colleagues at both the University Museum and other museums. One question that arises is about the alternative. What would happen if the University Museum decides to no longer show some of these human remains? Should they have a funeral for the ones they’re phasing out?

A collection that can’t be viewed is essentially dead

He can’t say anything definitively about that second matter. For him, it’s about making a deliberation: ‘Is there any added value to burying these remains that weighs heavier than treating them with respect, the way they have been for the past two centuries?’ He’s still looking for the answer.

Sliced-up man

No one knows how this ‘sliced-up man’ met his demise. All we know is that he was twenty-seven years old and that his body was frozen after his death around 1920, after which physician and anatomist Jan Willem van Wijhe cut him into seven pieces length wise.

‘In order to cut up the torso thusly, it is necessary to freeze the body in a mixture of ice and kitchen salt; this will make him hard as a rock and the body will make a sound like a bell when hit with a hammer’, Van Wijhe later wrote about the process.

It’s an example of the ‘frozen section technique’ that Pieter de Riemer invented somewhere around 1918. This involved freezing tissue before cutting it into thin slices, which allowed for a quick diagnosis of anything wrong.

But the sliced-up man served a different goal. His specimens gave medical students a unique look at the human body.

So far, Hendrikman has decided that the human remains that are being removed from the regular collection will go into storage. ‘It’s actually becoming more important to keep them, since they’re a part of history’, he says. ‘That way, they’ll still be available for educational and research purposes.’

Some of the current collection will see this same treatment in the future. ‘They’ll be respectfully moved to the storage at Zernike, where they’re keeping a hundred thousand other objects.’

Gradual change

Hendrikman has plans for a gradual change at the museum. The first objects to go are Petrus Camper’s skulls. Why them? It’s reasonable to assume that these skulls were obtained without permission, Hendrikman explains, and they were obtained during colonial times. ‘That’s reason enough to, at the very least, not show them off or display them. We have to be respectful towards our own history, but they shouldn’t be front and centre in our collection’, he emphasises.

The anatomical cabinet will be rearranged at a later date. It’s still to be determined what it’s going to look like, but the plan is for certain objects to only be available for educational purposes going forward. However, the collection won’t be removed in its entirety. ‘It is a museum collection, after all, and a collection that can’t be viewed is essentially dead. Collections that are no longer being used for education or research lose their value.’

Hendrikman hopes to make the planned changes over the summer, but understaffing will make this difficult. One thing is certain: some of the human remains will no longer be viewable by the public in the future. It’s up to the visitors themselves to decide if they’ll be missing that wow factor.