Abuse survivor Marco burnt out

The bruises don’t go away

Once, when he accidentally dropped a plank that was balanced on two computers, Marco Strijker had to stand next to his father, who was working. ‘That way, he could turn around and hit me, then go back to what he was doing.’

Strijker, now twenty-six, was abused by his father until he was eight years old. Many memories have faded, but he remembers enough to know what was done to him. The physical and mental humiliations continue to impact his life to this day, he says.

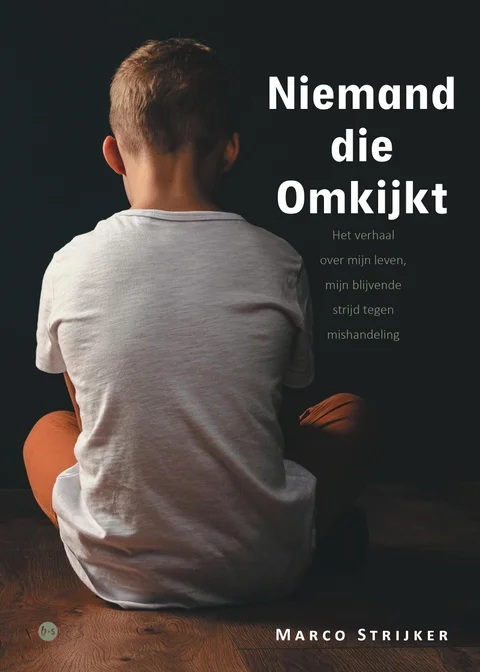

During his time as a student – Strijker studied business administration in Zwolle and moved to Groningen during that time, where he completed his master last year – his past came back to haunt him. Now he’s written a book, Niemand die omkijkt (No one looked after me) as a way to process his experiences.

Threats

His parents separated when he was less than a year old. His father abused his mother, and she moved with her two sons to a crisis shelter. Once they found their own place in Ruinen, a village 40 minutes south of Groningen, a visitation schedule was arranged: Marco would spend a weekend with his father every two weeks.

That’s when the physical abuse began.

I became very good at hiding what was happening

Because Marco and his brother would come home with bruises, his mother contacted Child Protective Services multiple times. But his father always managed to keep his visitation rights.

‘I became very good at hiding what was happening’, says Strijker. His father threatened to kill anyone young Marco loved if he spoke up ‘and I didn’t want to put anyone in danger’.

One of the most traumatic experiences he had was the time he had to spend a night in the basement as punishment, without knowing the reason behind it. With only a pillow, he was sent to the cold, dark space. ‘That was under the pretence of: if you don’t want to sleep here with us or be part of this family, then you can sleep in the basement.’

Limit

This continued until he was eight. ‘Parents can do a lot before a child takes action’, says Strijker. But at one point, he reached his limit. ‘One morning, I woke up much earlier than my father, and I felt that I had to do something.’

He gathered his things, sneaked downstairs, and tried to call the police. ‘I had imagined that I would be saved, that they would come with three police cars.’ When he couldn’t manage to make the call, he decided to go to the police station, walking down the street with his belongings stuffed in a pillowcase.

After only forty metres, someone from the neighbourhood intercepted him. ‘I’m having a fight with my father, and he’s going to kill me’, Marco told him. The man took him to his grandmother’s house, and the police were called. Eventually, they decided that Marco should go back to his father, because that’s where he was supposed to stay for the weekend.

To this day, Strijker doesn’t understand it. ‘How can you take a child back to the person he’s so afraid of when he says his father is going to kill him, without even having a conversation?’

During the remaining hours he had to spend with his father that weekend, he constantly thought they would be his last. But in the end, his attempt to run away did work, because Marco’s mother didn’t need to hear much to know that something was wrong. After that, he never had to see his father again.

Lonely

A childhood like that leaves its marks, Strijker discovered during his time as a student. ‘For example, I have low self-esteem. I’ve always had self-hatred, but it became stronger during that time.’

I was used to doing everything by myself, so I just kept doing that

For most students, those years are a period when they make many new friends. Marco, on the other hand, felt very lonely. ‘I isolated myself and was on my own a lot. I was used to doing everything by myself, so I just kept doing that.’ These were patterns he had learned in his childhood that he wasn’t aware of.

Presentations, which he had to give regularly during his studies, caused him extreme stress. ‘My vision would just cut out, and I had panic attacks.’ It went wrong during a presentation for his internship, where he didn’t even have to stand in front of the group. ‘All I had to do was sit and write down things that caught my attention.’d

When a question came up that he knew more about, he raised his hand to further explain the topic. Meanwhile, the discussion continued, so he thought the moment had passed. Until a woman focused her attention on him, and he had a blackout. ‘I was in a tunnel and only saw her’, he says. ‘Apparently, I gave the correct answer, but I didn’t realise it.’

Self-insight

Another internship placement, team development company Inn-spiratie, ultimately helped him move forward. Strijker continued working there during his master. ‘It brought me a lot of self-insight. They told me that my greatest strength was being able to do everything alone, but that it was also my biggest pitfall.’

He also owes his book to Inn-spiratie. When they asked him to come up with a very ambitious goal, the plan to write a bestseller was born. ‘There’s no real definition of it, so I decided it would be considered a success if 42,840 books were sold.’

There’s a constant voice in my head criticising me

That number isn’t random: ‘That’s how many children are abused in the Netherlands’, says Strijker. It’s an estimate, but professionals see it as the minimum. ‘These are the children we know about.’

The proceeds from his book go to the Het Vergeten Kind foundation (The Forgotten Child), which works towards providing a safe home and organising outings for children facing difficulties at home. ‘They take away their stress and allow children to truly be children.’

Relatable

Promoting the book is challenging for him, because he has to share his story each time. But it’s worth it: he has already been able to donate 5,000 euros. ‘And I believe there’s something relatable for everyone to read, even if you’ve never experienced abuse.’

On a personal level, his fight against abuse continues. Depressive feelings come and go. ‘It doesn’t take a lot to make me feel down’, says Strijker. ‘Not every day is all doom and gloom, but there’s a constant voice in my head criticising me. I’d rather not utter the literal words, but essentially, I just think, “What an asshole, I should be dead.”’

However, he has learned a lot over the past years, partly thanks to therapy. ‘I now realise that you don’t have to do it alone. I always thought you did, but there are some things where you can go further together. I wish I had known that earlier.’

Niemand die omkijkt (available in Dutch only) can be ordered here.