Stolpersteine for war casualties at the UG

Thirteen lives remembered

‘Look at him’, says Mineke Bosch. ‘With his small round glasses and the minute book for the Groningen Zionist Student Organisation under his arm.’

There are a few more photos of Groningen student Meijer Stern, always wearing the same glasses and carrying the minutes book, surrounded by other members of the Jewish student association. Bosch knows his parents weren’t happy that he was a member. ‘They felt he should trust God and shouldn’t be in a rush to go to Palestine.’

She also knows that together with Jewish physicist Boris Kahn, Meijer played music during the inauguration of the new rector in September of 1940, when collaborationist Johannes Kapteyn was made university boss during the war: they played Debussy and Loeillet.

Lives intertwined

Five months later, the new rector orchestrated the arrest of Jewish professor Leo Polak, who died less than a year later in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Meijer Stern and Kahn didn’t survive the war, either. ‘Right there is when all those lives intertwined’, says Bosch. ‘I think that’s so moving, but so painful.’

If we methodically researched it, we’d find much more

Bosch learned about Meijer’s existence when she was working as a secretary for the UG Representation Fund. This fund aims to increase the university’s visibility in the city of Groningen. One way to do that is through Stolpersteine: small, copper stones in the pavement in front of the houses victims of war used to live: Jews who were dragged from their houses to be deported, or resistance fighters.

Thirteen of these stones were placed over the past few weeks, and they’ll be officially revealed by current rector magnificus Cisca Wijmenga on Wednesday, May 4. Bosch wrote a booklet for the unveiling, digging into the lives of the people the stones are for.

Scarce information

The research was difficult, she says. Even though the information on them was scarce, these people came to life for her, even if only for a short time. Not just Meijer Stern and his music, but also Jetteke Polak, Leo Polak’s daughter, who protested during a speech by a new, German professor of internal medicine who had replaced a Jewish professor. As a result, she was arrested, eight months after her father had been detained. She was murdered in Auschwitz in November of 1942.

Another student she researched was Kars van den Bergh, a member of student association Vera. He was part of a gang that robbed printing presses to steal ration cards. But then he assisted in a weapons drop in June of 1944 that the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD) was aware of. Kars was injured, arrested, tortured in the camp in Vught and executed by firing squad ten days later.

The university didn’t really stay strong during the war

Writing the booklet enabled Bosch to briefly have a relationship with the students and researchers from back then. But she also noticed something else, which is that we don’t actually know who exactly we should be commemorating. ‘No one ever thoroughly researched victims of the Second World War from the UG’, she says.

Take that picture of Meijer Stern. Two of his fellow members, who we can assume were enrolled at the university, are unknown victims: Julius de Vries and Emanuel Kats. Their names are not on any of the plaques at the Academy building. ‘I think if we were to start methodically researching it, we’d find much more’, says Bosch.

Track down names

A book on the history of the University of Amsterdam has entire lists of casualties, she says. ‘Sure, many Jewish people were forced to move to Amsterdam, but they didn’t, or in fact, couldn’t, register there. So that doesn’t explain the difference.’

That desperately needs to be figured out, she feels, because she’s worried the Jewish community is not currently properly represented in the UG’s commemoration tales. ‘We might have to track down a thousand names of people who were students back then’, she says. ‘But that shouldn’t be too difficult.’

It’s especially important today, says Bosch. ‘It’s important for us to remember them. Let’s be honest: the university didn’t really stay strong during the war. I think it’s important that we remain aware of the people who were excluded and murdered. So few of them are left and it’s us, the members of the academic community, who had a meaningful relationship with them.’

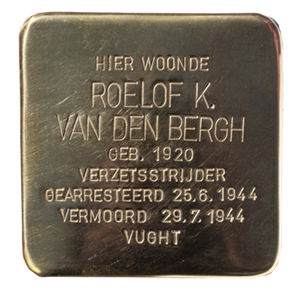

1Kars van den Bergh

medical student

Stationsstraat 3

Kars was nineteen years old when he started studying medicine in 1939. He joined the Dutch Reformed student association Vera, which is telling: Vera members were much less likely to to obey the German occupying forces than other associations. Many of them refused to sign the loyalty declaration and went underground.

Kars soon joined the resistance. He was part of a gang who robbed printing presses. He later left for Rotterdam, where he helped people leave for Belgium. His participation in a weapons drop led to his demise. His gang was betrayed and Kars was injured. He was arrested and died by firing squad on July 29, 1944.

Sluit

2Jacob Domela Nieuwenhuis Nyegaard

alumnus

Pelsterstraat 33

Jacob, also known as ‘Koo’, was working as a lawyer in Groningen when the Germans invaded. He’d graduated from the UG with a degree in law in 1926. He married in 1927 in Denmark but settled in Groningen after all.

After the invasion, he fought hard to oppose the German occupation. His house at the Coendersweg served as de facto headquarters for the Ordedienst, a group of people preparing for what came after the war.

Jacob was shot to death on the stair in his house on September 25, 1944, when the Gestapo tried to arrest him.

His 74-year-old father who was staying with him at the time found him there and was ultimately arrested and taken to the Scholtenhuis after going on a public tirade against Hitler and the Nazis from the open window of his murdered son’s house, and wearing orange clothes in public in protest.

Sluit

3Boris Kahn

Physics Laboratory custodian

Coendersweg 4/2

‘Young scholar, excellent Hebraist, artistic man. Health: good.’ This is written on Boris Kahn’s personnel card for the Jewish grammar school in The Hague. And: ‘Previous employ: custodian physics laboratory and mechanics lecturer at University of Groningen.’

Kahn, being Jewish, had been forced to move to Amsterdam in 1944, leaving his house at the Coendersweg behind.

He’d only been employed at the UG for two years. Kahn was born in Switzerland in 1911, the son of Russian parents, but moved to the Netherlands as a child. He went to university in Utrecht, started working in Groningen in 1939, and played music when the new rector was installed in 1940.

But he was relieved of his duties that same year. He taught in schools in Leeuwarden and Groningen for another year, but that, too, came to an end in 1941. He was arrested during a raid in 1943 and a request from the faculty to put his name on a list of ‘protected Jews’ was denied. Kahn was deported to Sobibor and was murdered there on July 23, 1943.

Sluit

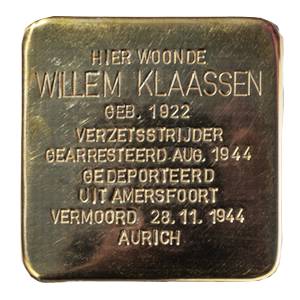

4Willem Klaassen

medical student

Schuitendiep 1b

Willem Klaassen never knew what a ‘normal’ university looked like. When he started his medical studies in 1941, Jewish employees were already banned from working.

Not much is known about his time in Groningen. It is known, however, that he quickly became involved in disseminating the illegal magazine De Ploeg, of which between five hundred and four thousand issues were published each month in Groningen and The Hague.

In 1944, Willem moved to Amersfoort, where he was arrested in August after several distributors of De Ploeg had been detained. He ended up in the concentration camp Engerhafe in East Frisia, where he was forced to build tank moats. The prisoners were worked to death. There was no medical care and hygiene at the camp was bad, which led to many disease outbreaks. Willem died of an illness on November 28, at twenty-two years old.

Sluit

5Denis Mesritz

law student

Oostersingel 130b

By German definitions, Denis Mesritz was half Jewish. Nevertheless, he was able to escape the restrictions somehow. He easily passed his candidate’s exam in law at the UG and earned the title of master in 1942.

In the meantime, he was heavily involved in the student resistance movement. He was involved in the Raad van Negen, an organisation consisting of representatives from all Dutch universities and technical colleges. Denis supervised the creation and publication of their journal De Geus.

Once he’d earned his degree, he set up shop as a lawyer in The Hague. There, he founded another illegal magazine in 1943: De Toekomst. He also took over editorial duties of the popular magazine Ons Volk when its leadership was arrested in January of 1944.

Four months later, it was curtains for Denis. He was arrested on the train to The Hague and murdered on March 19, 1945, in the Rathenow concentration camp.

Sluit

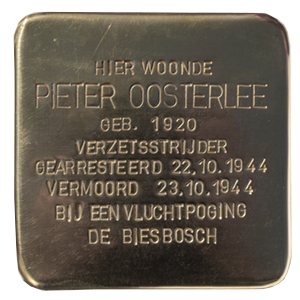

6Pieter Oosterlee

medical student

Oosterstraat 36a

‘He was all too aware of the risk. But he loved the Netherlands and its citizens’, wrote Pieter Oosterlee’s parents in the Nijmeegse Dagblad on May 12, 1945.

The Groningen medical student had been shot to death seven months earlier during an escape attempt from the Germans.

Shortly after he’d started his studies in Groningen, Pieter moved back in with his parents in Nijmegen, where he became an active member of the National Organisation for Helping People in Hiding. He helped British pilots escape to Lisbon by guiding them through the desolate Biesbosch area and arranged identity cards for people in hiding.

When the area south of the Biesbosch was liberated in the fall of 1944, he was in charge of contact with the Allied Forces. However, he was betrayed and arrested on October 22. He was imprisoned in the Juliana school in Tiel and murdered the next day as he attempted to escape.

Sluit

7Benjamin Pais

medical student

Oude Kijk in ‘t Jatstraat 69a

It’s possible that Benjamin Pais and his fellow medical student Mark Zilverberg knew each other. Perhaps they even relied on each other for support when they were being transported to Auschwitz. Their fates are just so similar.

Benjamin was a medical student who lived with his wife Sera Meijer and her parents in the Oude Kijk in ‘t Jatstraat. But he was detained and deported to Westerbork on New Year’s Eve 1944.

He was held there for four months and then transported to Theresienstadt on April 5 and to Auschwitz on May 18. He was part of a transport of sick people from Schwarzheide to Bergen-Belsen, which also included his fellow student Max. Benjamin died in Bergen-Belsen on March 1, 1945.

Sluit

8Jetteke Polak

medical student

Van Houtenlaan 52

Her father, well-known professor Leo Polak, had already been arrested and transported to a concentration camp. But that didn’t stop Jewish Jetteke Polak from demonstrating while the new, German professor of medicine held a speech. This professor was replacing Jewish Leonard Polak Daniels, who’d been relieved of his position.

Together with five other students, all male, Jetteke, who was a member of Magna Pete and the Dutch Zionist Student Union, set up shop at the Academy building to see which professors entered the building. After all, most professors and student representatives were boycotting the event.

The students ended up being arrested. The men were transported to camp Amersfoort and all but one were released. Jetteke was sent to the women’s concentration camp Ravensbrück near Berlin and was murdered in November of 1942 in Auschwitz.

Sluit

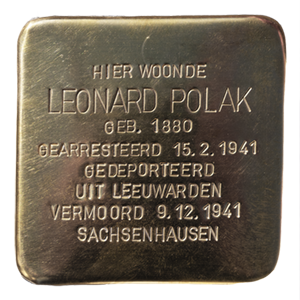

9Leo Polak

philosophy professor

Van Houtenlaan 52

If only Leo Polak had taken his family to the New School for Social Research in New York when he was offered a professorship there in December of 1940. Instead, he decided to protest his suspension from his job as a professor in November of 1940.

The famous philosopher and freethinker wrote indignant letters to his colleagues at the arts and philosophy departments, as well as to rector magnificus Kapteyn, calling the German occupying forces ‘the enemy’.

The rector showed these letters to the Germans, who used it as a reason to arrest Polak on February 15, 1941.

Polak was interrogated at the Scholtenhuis and then transported to the prison in Leeuwarden. In the meantime, he was officially fired, his pension was revoked, and his family was kicked out of their house.

Polak was transported to Sachsenhausen on May 7 and was murdered on December 9, 1942.

Sluit

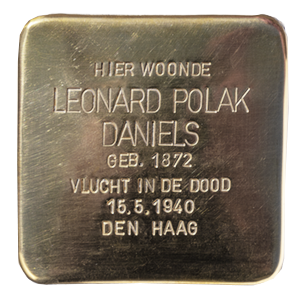

10Leonard Polak Daniels

professor of medicine

Eemskanaal 3

Professor of internal medicine Leonard Polak Daniels was already helping Jewish students who were trying to flee the German oppression as far back as 1933. Unfortunately, these students weren’t welcome in the Netherlands, which included Groningen.

By September 1933, approximately thirty-five requests had come in from Jews who wanted to continue their studies in Groningen. But the Netherlands was worried that universities would get ‘overcrowded’ and that Dutch citizens would lose out on job opportunities. Even though Polak Daniels passionately argued to accept as many students as possible, most requests were denied by the minister in charge.

Polak Daniels also refused to set foot on German soil and as rector magnificus, he turned down an official invitation to a conference at the University of Heidelberg: a unique and political act.

After the German invasion and the bombing of Rotterdam, he knew exactly what was in store for him. Polak Daniels, who was staying with his wife at their son Anselmus’ house in The Hague, decided to end his own life. Helped by his son, he and his wife each took a sleeping pill on May 14, 1940, followed by a lethal injection of potassium cyanide.

Sluit

11Salco van Staveren

medical student

Oosterhaven 17

Even during the war, there were students who weren’t a fan of Vindicat’s hazing practices. Samuel ‘Salco’ van Staveren was one of them.

The medical student had moved to the Oosterhaven on October 1, 1940 and he was the only Jewish student to join the Groene Uil, an association made up of students who didn’t want to subject themselves to hazing. At the association, he was an enthusiastic cabaret performer.

Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to enjoy student life for very long. On February 3, 1942, he was forced to move to Amsterdam. There, he was put on a transport of Westerbork. He managed to get married in a transit camp, mere days before he and his bride were transported to Auschwitz. Salco was murdered there on September 6, 1942.

Sluit

12 Meijer Stern

medical student

Tweede Willemsstraat 48b

Medical student Meijer Stern was there when war rector Kapteyn was instated in September 1940. He was one of the musicians providing music for the switch in rectors, as was Jewish physicist Boris Kahn.

But several months later, Kapteyn did nothing to prevent Jewish professors from being dismissed from their position, and he betrayed Leo Polak to the Germans.

Meijer was born and raised in Groningen. He was a member of the theatre association at the Praedinius Gymnasium and sang in his synagogue’s choir. As a student, he joined the Groningen branch of the Dutch Zionist Student Organisation, against the wishes of his parents.

He got engaged to Jeanette Cohen in 1942 and together, they moved to Amsterdam, most likely because they were forced. After that, it looks like he and his wife tried to escape to Switzerland. The pair was detained near the border in the French municipality of Pontarlier. From there, he was sent to the Drancy transit camp and then deported to Auschwitz, where Meijer Stern was murdered on September 30, 1942.

Sluit

13Max Zilverberg

medical student

Anna Paulownastraat 9a

Medical student Max Zilverberg had been at the camp in Westerbork for almost a year when his family from the Anna Paulownastraat was also taken there. After that, he spent nearly another year in the concentration camp, making him one of its longest ‘residents’. This meant he was transported to Theresienstadt on April 5, 1944, instead of Auschwitz, where he immediately would have been taken to the gas chambers. He was on a list of ‘Jews who’d made themselves useful in the construction and storage operations of Westerbork’. His fellow medical student Benjamin Pais was on the same transport.

Unfortunately, it didn’t help him one bit, because he was transported to Auschwitz after all on May 18, after which he and Benjamin were taken to Bergen-Belsen on a sick transport.

Max was there when Bergen-Belsen was liberated, but ended up dying there after all on May 31, 1945, mere weeks after the liberation of the camp.

Sluit