When the Norse discovered America

Vikings and solar flares

Well… there is definitely enough wood here, thought Margot Kuitems, when she entered the storage room in Halifax, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia in November in 2018.

Thousands of items were stored there, all packed in hundreds of carefully labelled boxes. Items that may seem insignificant to most people – scraps of wood – but the fact that they were found at the only known Viking settlement in the Americas makes them invaluable.

Future

And everything was kept, not just artefacts like the stone oil lamp they found, or a birch bark case. Every piece of wood that chief archaeologist Birgitta Wallace came across in the almost fifty years she has been researching the UNESCO World Heritage site L’Anse aux Meadows she kept. ‘She really thought about future purposes’, Kuitems says happily.

Now, that foresight was going to pay off, because Kuitems – who works as a postdoc at the Centre for Isotope Research of UG – was there on mission to select some of these seemingly unimportant finds to solve one of the biggest mysteries about the Viking presence in North America. When were the Norse there exactly? She would be using a revolutionary new method that has been put to the test only once before by the same radiocarbon (14C) specialists at the UG.

Reconstruction of one of the Norse buildings in L’Anse aux Meadows. Photo by Douglas Sprott (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Newfoundland

L’Anse aux Meadows is a special place. Situated at the most northern tip of Newfoundland it contains the remnants of a settlement. Most interesting, though, is the fact that the buildings there were built in a typical arched style that was also found on Iceland and Greenland.

Previous analyses couldn’t actually distinguish between different periods within the Viking age

Norse ornaments were found too, and evidence of metal tools of a time that the indigenous people in the area only used stone tools. So there is no doubt about it: this is a Viking settlement and proof of the fact that the Norse did go to the Americas centuries before Columbus.

However, no one knows exactly when it was built. Icelandic Sagas tell the story of Leif Erikson, the son of Erik the Red, who is supposed to have discovered the Americas and reached Vinland – as he called it – around the year 1000 AD. ‘But that was written down in the 13th century, two centuries after the event’, says Kuitems.

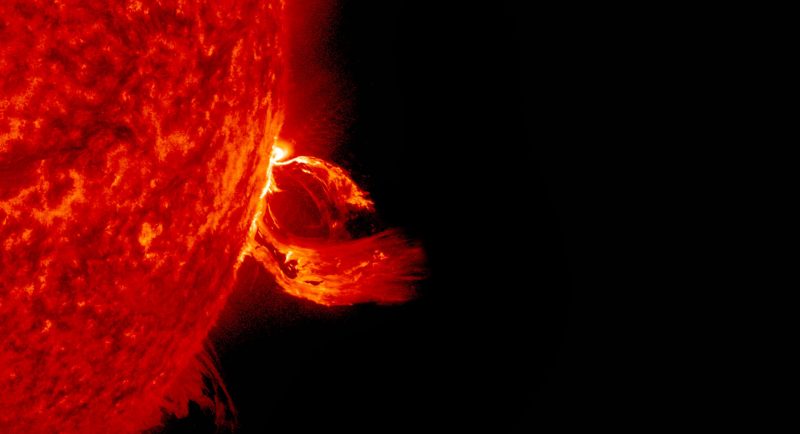

Huge solar flare in 992 AD were responsible for excess 14C in the atmosphere, that is still measurable today

Radiocarbon dating

And even though radiocarbon dating was done on 55 items found in the so-called Norse layers, it was only possible to estimate their age to a period between 7th and 12th centuries. With radiocarbon dating, the further you go back in time, the less accurate the dating becomes’, says Michael Dee, who is associate professor of Isotope Chronology at the Centre for Isotope Research. ‘Previous analyses couldn’t actually distinguish between different periods within the Viking age.’

But a brand new dating method, developed in Groningen, could.

The idea had hatched in the mind of Dee years before already, when he was designing the ECHOES project. Dee leads the ECHOES project at the Centre for Isotope Research and has been studying spikes in 14C caused by extremely powerful solar flares for years now. One is known to have occurred in the year 774 and another in the year 992 AD.

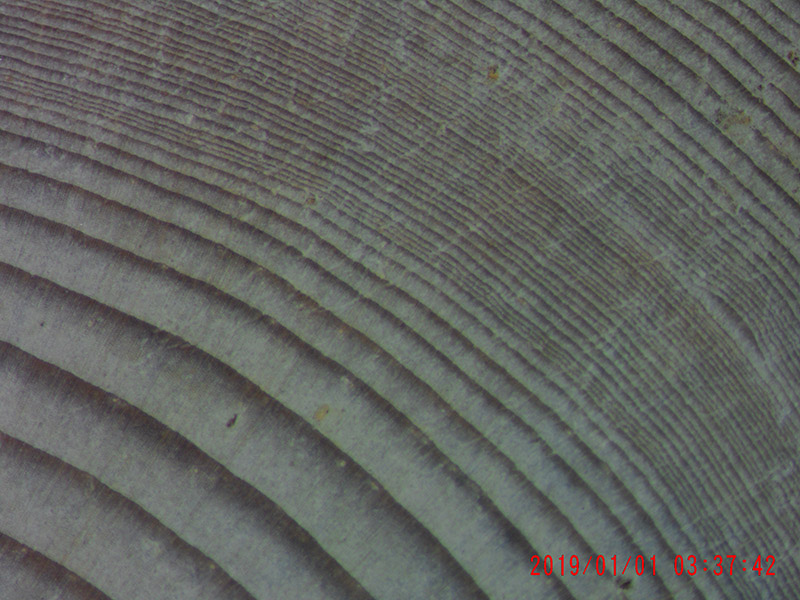

Tree-rings

These spikes were so powerful that they created excess 14C in the atmosphere which can still be measured in the rings of trees that were alive at those times and absorbed the rare isotope. If he and his team were lucky, they might be able to pinpoint the 992 spike in one of the tree-rings in the wood that was found at L’Anse aux Meadows.

The spike from 992 is a smaller event, we were not sure the signal was clear enough

Once they had done that, they would know this ring was created in the year 992 AD. From there on, they would only have to count the rings back to the bark and they would know in what year the tree was actually cut.

Seems simple, but Dee and Kuitems had only used the method once before, when they dated the mysterious island fortress of Por-Bajin to the year 777 AD. ‘We proved the method worked’, Kuitems says. ‘But then we used the 775 spike and the one from 992 is a smaller event. We were not sure the signal was clear enough.’

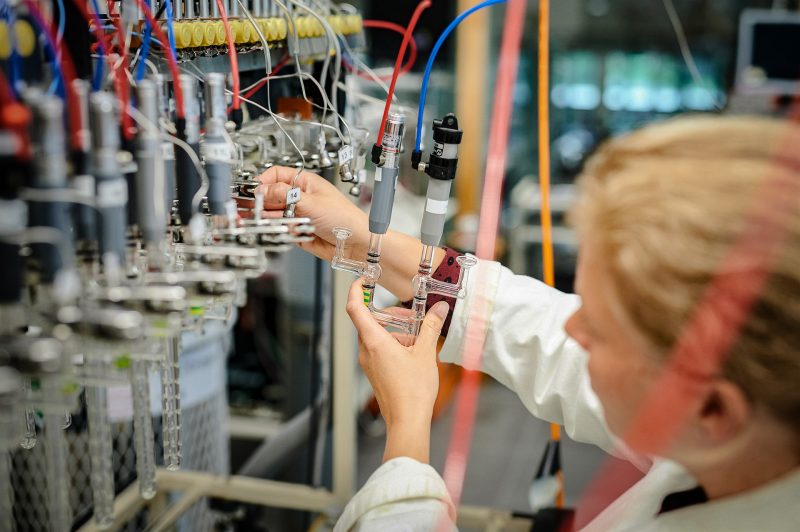

Margot Kuitems working on the graphitization of the samples

Razor

Also they would need some pieces of wood that actually had the bark still on, the cooperation of not only the Canadian archaeologists, and that of the Canadian government. ‘To find the spike, we need to split the rings with a razor and measure the 14C of each one separately. Sometimes they have a width of 1 mm, but sometimes it’s also three in one millimetre’, Kuitems says.

However, they did obtain the cooperation of both archaeologists and the government. Kuitems was able to select useful pieces of wood. But then, when she and Dee started measuring, they couldn’t find the spike. ‘We expected to find it in the outermost ten rings’, she says. ‘Which would set the date to around the year 1000 AD.’

Not finding the spike could mean a number of things: the spike might not be measurable, or the Vikings had come to the Americas much earlier than expected, or much later. Also they started to run out of wood. ‘We needed to have new samples if we wanted to keep going’, Dee says. ‘But we did panic a bit as we had spent so much time on this already. Then, the pandemic broke out, which meant we couldn’t go to Canada.’

Above: Explainer video of radiocarbon dating by the Echoes project

Lost

Luckily the Canadians agreed to send new samples by a courier service. Only for that service to lose the package! Dee still remembers the horror of those weeks. The endless telephone calls with customer service not wanting or not being able to understand that a package with a few pieces of old wood was really, really valuable. The fact that we had to go back and beg for even more samples from the Canadians.

471 years before Columbus there were Europeans cutting up trees in the Americas

‘In the end it was agreed that the replacement pieces would be flown to England with a commercial pilot and I volunteered to travel over and pick them up in London’, Dee remembers. At which point the original package was suddenly delivered to the post room, leaving Dee and Kuitems with two sets of samples!

And then, finally, they struck gold. ‘We found the spike in a tree stump that was probably used for clearance of the site’, Kuitems says. ‘There was also a big log and a branch with some smaller branches. They were just thrown aside in a swampy area. That’s why it was preserved.’

Columbus

It turned out that every item was cut in the same year, Dee says. ‘So we finally had a date. 471 years before Columbus there were Europeans cutting up trees in the Americas. And we know from plant remains found at the site that they went further south too.

We don’t know if they ever went as far as the mainland United States, but even so this traversal of the Atlantic was the first time the entire globe had been actually encircled by people.’

Now it’s time for historians and archaeologists to carry the research further, Dee says. This finding can shed more light on the surprisingly detailed Icelandic sagas about Leif Erikson and his travels and how we should read them.

Propaganda

And that’s an important story to tell. ‘There’s a growing body of evidence that the story of the Vikings going to the Americas was actually relatively common knowledge in medieval Europe. So it’s quite possible that the story the modern world has received – that it was this terra incognita across the Atlantic – was a form of propaganda, serving the purposes of the ruling European families.

This technique makes it possible to better analyse what has actually happened. We can also put to the test the stories contained in the Viking sagas. They have an enormous amount of detail in them, about contact with the indigenous American People, for example.’