How I got my money back

Scammed!

‘I am such a fool.’ The rebuke echoes in my head.

I’ve been having a lovely New Year’s dinner, surrounded by friends. But now my hands are trembling as I scroll through a message from a friend on my phone. It’s evidence that the person I paid to bring a package from my home country to the Netherlands is a liar.

I’ve totally been scammed.

Gambit

A week earlier, I had been desperately looking for someone who could bring some stuff for me from China. My notebook, my favourite perfume, and a brand-new phone which allows me to use my Chinese SIM card here. Things like that cannot be sent by mail, and the most common solution for Chinese students is to pay someone who is travelling anyway and let them take it in their luggage.

Yes, it’s a gambit. But it’s also the only option.

And then I saw the message in a group chat: ‘Returning from China to the Netherlands on January 7, I could bring your items for a fee.’

The information provided looked sound. The guy – who went by an alias of one single emoji: 😊 – seemed to know his way around the Netherlands. That made sense, since he said he came from Fuzhou, a region in China from which many people migrate to developed countries – either by legal or illegal means.

We made a deal. I paid him the shipping fee, had my parents in China send him the package, and waited for my notebook, perfume, and new phone.

Ghosted

But here I am, staring at the screenshot my friend and fellow UG student Chen has sent me. She just found out that the same guy scammed her twice in two weeks. The first time was at the end of December. She wanted to send her cat to the Netherlands and paid the person who was supposed to arrange this a large amount of money on the grounds of various formalities. But then he stopped replying and ghosted her.

The same guy scammed my friend twice in two weeks

The second time the man used another social media account to set up an elaborate play in which he tried to trick her again and was ‘helping’ her to track down the first person. Again, she sent him money. Again, she was ghosted.

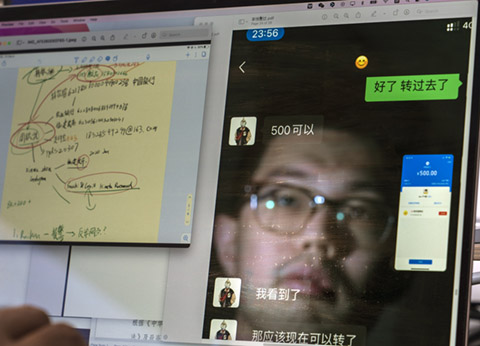

‘Look’, she texts me, showing me the screenshots of his social media account. ‘He’s using the same two accounts to play different characters, that’s what gives him away.’

I look, and realise this guy has also taken my phone, my notebook…

It keeps ringing in my head: ‘I am such a fool.’

Old ladies

In 2019, 13 percent of Dutch residents aged fifteen and over indicated they had been victims of one or more cybercrimes. However, only one in twelve went to the police. Fraud Help Desk, the Dutch anti-fraud hotline, received about 530,000 reports of online scams last year, a number that has been growing rapidly in recent years.

Though you may think this only happens to old ladies who are just not that internet savvy, think again. ‘We see that everyone, from highly educated people to lower-skilled people, is falling prey to these scams’, says spokesperson Tanya Wijngaarde of Fraud Help Desk. ‘Even people who themselves work in IT. There will always be a moment that you are tired, a little less attentive.’

Also, scammers often target specific groups and cater their messages to their specific situation. Like – in this case – Chinese students.

No help

Just like Chen, I was scammed before, too. Last time, in December 2020, I kept all evidence and reported the scam to the Dutch police, Facebook, my bank, and my insurance company, but they all told me: sorry, we cannot help you. The letter from the Dutch police is still in my drawer: ‘Every day, the police receive many new cases. We cannot address all of them.’

So I didn’t feel like going to the police again. My friends told me to forget about the whole thing. ‘You’ll never get your money back’, they said. My parents told me: ‘Son, we can buy you a new phone.’ Even Chen said: ‘I’m giving up. Nobody can help us.’

Should I really let this guy get away with it?

But I was so angry. Should I really let this guy get away with it?

Chen and I started digging. Putting together what we knew, we found reports of this man running scams going back to 2020 from posts on a website specifically meant for Chinese people in the Netherlands. In the last two weeks alone, we discovered, at least ten students from Groningen had been talked out of their money.

Most of them lost less than 3,000 yuan (approximately 411 euros) – a smart tactic, because the Chinese police only deals with cases over that amount, as prescribed by law. When it’s less than 3,000 yuan, you can’t even report the crime to the police.

But I, Chen, and Tang, another UG student, lost more than that, so I got my parents to go to the police. ‘This is a Dutch case, which means we have no jurisdiction’, we were told.

Tang went to the Dutch police. ‘This is a Chinese case. We have no jurisdiction’, he was told.

Research

We researched Chinese criminal law and found the police had to take our case, whether they wanted to or not. My parents went back, having been rejected three times already, but this time with all the documentation we had gathered. Finally, after a week of countless phone calls, discussions, searches, and even daily crying – they were successful. It took a long bureaucratic process, with different police departments trying to establish who should actually do the work, but we received a piece of paper indicating they had indeed taken the case.

Yes!

Now Chen could use my statement to get the police in her hometown to accept the case. Tang could do the same.

That meant we had almost won. The Chinese government has extremely high requirements for the police to solve crimes. So once they do take up a case, they will almost certainly take it to the end.

Threatening message

China has strict e-commerce regulations and it turned out the scammer hadn’t been discreet enough. Within no time, the police found his mobile phone number and bank card. They had him. Only one tiny problem: Covid travel restrictions prohibited them from actually arresting him. ‘But we can call him, asking him to give your money back.’

Travel restrictions prohibited the police from arresting him

We decided we could do the same. So I sent him a message, too, threatening: ‘Pay our money back or spend your new year in jail.’

Then we sat, we waited, and we hoped.

After two days, I got a notification from my bank. I quickly checked and there it was. Over a thousand euros in my account from the scammer. Chen called. She too had gotten all of her money back, as had Tang. We received messages from him as well, asking us to withdraw our report to the police, since we had our money back.

We did not.

Justice

But the question just keeps playing in my mind: we have been lucky enough to get our money back, but the scammer won’t be arrested and won’t be held legally responsible. Is this really justice? Who will stop him from doing this again?

This Sunday I got a message from a friend. He sent me a piece of chat history in another group chat in WeChat, and asked me: ‘Is this the same guy?’

It was.