Petrus Camper and colonialism

The things we don’t see…

This exhibition is about the things you don’t see.

Not included: the skull belonging to a Khoekhoe woman who died approximately 250 years ago in a little town now called Gordon’s Bay, to the east of Cape Town, South Africa. She was a mother of grown children and her voice has even been described. However, a day after her death, she was robbed from her grave. Her head was sent to the Netherlands.

Another object that’s not included in this exhibition: the same woman’s ears in formaldehyde, preserved so everyone could see the dark colour of her skin.

Other things have been excluded as well: pieces of skin in formaldehyde, various body parts, even genitalia, and many more skulls. This exhibition explicitly doesn’t show any of the human remains that once belonged to famous anatomist Petrus Camper, who worked as a professor in Groningen from 1763 to 1773.

Legacy

The exhibition makers didn’t think it was right. The exhibition ‘Entangled Stories’, which opened last week at the University Museum, shows the way Camper’s legacy is interwoven with colonialism and the development of scientific racism. That means we can no longer pretend that the human remains that have been in the UG’s possession for the past two hundred years are simply ‘objects’.

This is an ancestress who isn’t where she’s supposed to be, which is in her grave

‘We may see these specimens as something that’s been studied for the past 250 years, or something to gape at in a museum. But for others, they may be an ancestress, someone who isn’t where she’s supposed to be, which is in her grave on the other side of the world’, says museum director Lars Hendrikman.

The exhibition is part of the international research project Pressing Matter: Ownership, Value and the Question of Colonial Heritage in Museums by the Dutch Science Agenda. The project focuses on the way colonialism still affects Dutch society. The treatment and restitution of ‘colonial objects’ is an important part of this project. Petrus Camper, while seen as a hero in the Groningen history of the university, owned many of these objects.

The ‘lively orang’

On Sunday, 9 June, 1772, the VOC ship ‘Ritthem’ arrived at the island of Texel, after a three-month journey that started at the Cape of Good Hope. On board was a ‘lively’ orang-utan from Banjarmasin, Borneo.

‘The animal is in poor condition, and very sluggish, but also not in the least menacing, and lets people handle it as much as they want. It also likes white wine, and knows how to remove the cork from the bottle, as long as it is not stuck too fast in there. But since it is sensitive to the cold, it will therefore roll itself up in a wool blanket and then disappear back into its cage.’

Earlier attempts by Camper and other scientists to transport a live orang-utan to the Netherlands had failed. But this one was given to Willem V’s zoo in July.

It was outfitted with a leather collar around its neck, with a chain that was fastened to a long iron pole. The animal managed to escape from his collar once, after which he climbed the beams in his cage and opened a bottle of wine. It took three men to wrestle him to the ground and put the collar back on, a little tighter this time. They also nailed the chain to the floor, so he couldn’t escape again.

Unfortunately, the ‘lively orang’ quickly fell ill and died on 22 January, 1777. Camper dissected the animal, later writing: ‘It’s not unlikely that the lack of proper exercise, adequate food, and the lack of warm air they are normally used to, were the main cause of the premature death of this animal in our cold region.’

Anatomical research

Internationally, Camper is mainly known for his measurements of ‘facial angles’, which he used to categorise people in various ‘national characters’. As far as he was concerned, this had nothing to do with racism: he was simply making a classification. But nineteenth-century racial scientists co-opted his work, and his reputation has suffered from this.

In his own time, he was famous for his comparative anatomical studies. He was one of the people in the Netherlands to dissect people of colour. He also studied countless animals, ranging from anteaters and rhinoceroses to John Dories and lions. Except he needed a way to get them.

‘We knew that the colonial relationships played a part in getting human and animal remains to the Netherlands’, says guest curator Lisette Jong. ‘We’re not just talking about the Khoekhoe woman’s skull, but also skulls of other enslaved people, as well as orang-utans from Borneo and elephants from Sri Lanka.’

Sending objects

Camper used his extensive networks of acquaintances and former students all over the world, asking them to send him objects.

There’s another side to who he was and what his legacy is

He even managed to get hold of a Cape lion and bluebuck. Both of these animals are sacred to the Khoekhoe people, but went extinct a long time ago. The taxidermied specimens were most likely lost in the 1906 fire at the Academy building. Other animals, like two young elephants, were shipped alive to the Netherlands, where they were kept in horrible circumstances, if they survived the journey at all.

Those are the things this exhibition wants to draw attention to. ‘We want to look beyond the hagiographies’, says guest curator Paul Wolff Mitchel. ‘There’s another side to who he was and what his legacy is that rarely has been brought into the conversation.’

Provenance

Camper wasn’t the only scientist who went about his work this way. But his collection, which has been at the UG since 1820, is an ideal example of how science worked in the eighteenth century. Researchers went on an archival search to find as much information as they could on the various objects, by linking them to Camper’s letters, among other things.

Knowing the whole story changes how we approach remains in museums

‘These objects have been disconnected from their histories’, says Wolff Mitchell. ‘But knowing the whole story, in this case of rather graphic violence and with the direct link with grave robbing, it changes how we approach remains in museums, whether they be those of humans or animals.’

Wolff Mitchell was able to unravel exactly which of the museum’s skulls belonged to the Khoekhoe woman that Camper’s former student Hendrik le Sueur sent him from South Africa. The learned Le Sueur wrote to me at the end of January 1774 that he […] had cut off the head of this elderly woman after her death and taken it with him’, Camper wrote about the skull.

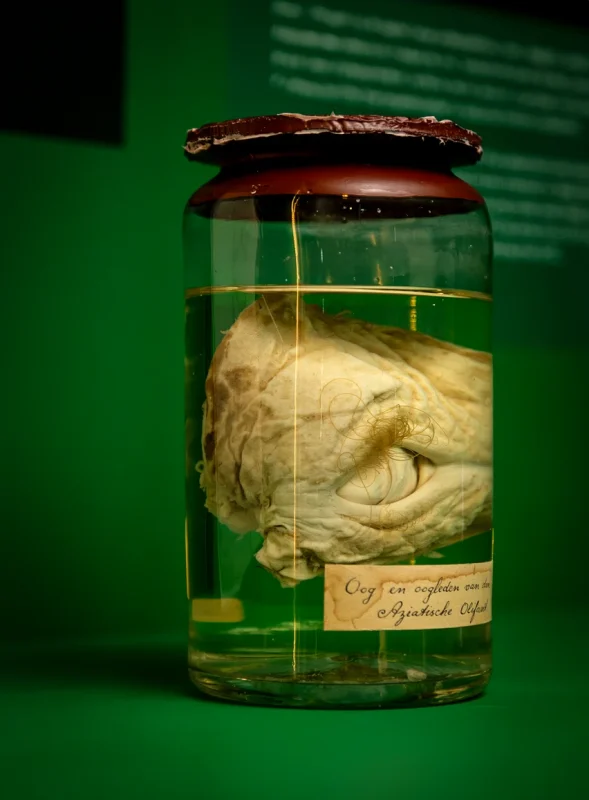

But there’s more: Jong was able to link the head of a young orang-utan in formaldehyde to some of Camper’s drawings. His former student Johannes Paulus Hoffman, stationed as a surgeon in Batavia, sent him the animal in 1770, preserved in arak, a local spirit. Upon arrival, the animal’s organs had turned to mush, but Camper made a cast of the head, stretched the ape’s skin over it, and preserved it. The orang-utan’s head is included in the exhibition, as is an elephant's eye belonging to an animal from Willem V’s personal zoo. The animal passed away after living in the zoo for five years, after which Camper dissected it at his estate near Franeker.

Empathy

Together with paintings, drawings, audio and video materials, the head invites museum visitors to take a closer look, says Wolff Mitchell. ‘Their stories enable a more empathetic gaze’, he says. ‘And that is also what this exhibition is about.’

What’s next? There are countless other objects of unknown provenance in the Camper collection. ‘Universities and museums will continue to grapple with colonial legacies in their collections and their academic heritage.’

But it’s also important to realise that Camper functions as a case study. ‘Doing further provenance research is very important and I do think we can find more information’, says Wolff Mitchell. ‘But I also think that really interrogating the collection through this contextualising lens gives us a lot more insight into his time than the focus on him as an individual.’

The elephant’s eye

Elephants, Petrus Camper determined, can’t cry. They have no tear ducts, ‘not a single trace of such an opening’. They did have eyelashes, but they certainly weren’t ‘eight thumbs long’, as some contemporary researchers sometimes claimed. ‘I will preserve the eye in its entirety, including the eyelids, to confirm all this’, he wrote in 1774.

It was one of the most important results of the eighteen long days Camper spent dissecting an elephant from Willem V’s zoo. The animal passed away in February and was transported to his estate in Friesland, where he tried to determine the differences between elephants and human beings, spurred on by the debate that argued that elephants were ‘the largest human being among animals’. They were considered to be sensitive and loyal. Some researchers even believed that elephants had sex in the missionary position. Supposedly, no one had ever seen them do this because the elephants were embarrassed.

After countless drawings and observations, Camper thought this highly unlikely. He did, however, think that the elephant was closest to human beings.

But what he didn’t do was wonder if it was okay to catch these animals and use them, which often resulted in its death. Other natural scientists and abolitionists at the time did do so. They thought the animals died of homesickness and depression over their imprisonment. Just like in enslaved people, the feeling had settled into ‘the deepest parts of their heart’.