Concerns about money and climate

No kids for us

It’s 2005. A primary school teacher asks her kindergarten class what they want to be when they grow up. Nienke Koedoot (23), today a student of pedagogical sciences, is four years old. She looks at the white piece of paper in front of her.

Drawing slowly, she draws what she imagines her future will look like: a torso with a set of arms, legs, and a head. That’s future Nienke.

Then, she draws another figure on the paper. It’s a lot smaller and being held by the bigger figure. ‘What do you want to be when you grow up, Nienke?’ the teacher asks, looking over her shoulder. Nienke looks up and answers firmly: ‘I want to be a mommy.’

Nienke remembers how one by one, her classmates started saying stuff about her drawing. ‘They were like, that’s not even a job’, she says, laughing. ‘But I simply knew that I wanted to be a mother. From when I was very little.’

More hesitant

Back then, wanting children was fairly obvious, but it no longer is. Several international studies have shown that young people are considerably more hesitant about having kids, in part because of their concerns about the climate.

My child would grow up in an even worse financial situation than I did

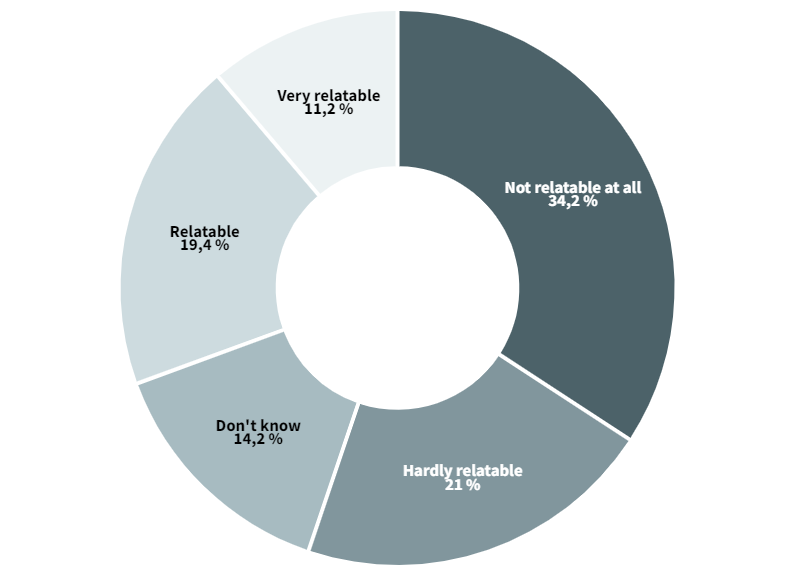

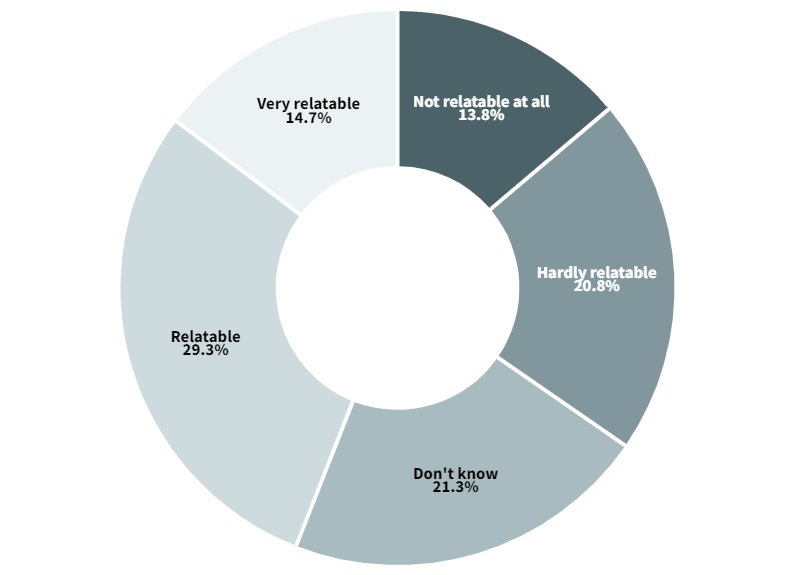

An UKrant survey held among 614 UG students showed that at least 22 percent of them definitely do not want children. Another 24.3 percent aren’t sure whether they want to be parents. Nearly half of the students – 44 percent – say they think fewer and fewer of their friends want kids.

Asked why they didn’t want children, 39 percent said they simply wanted a child-free life. But the biggest reason was concerns over the political and economic instability in the world: 54 percent of respondents checked this answer.

No house

Biology student Irene ten Have (24) is one of the students who thinks finances will get in the way of a picket fence scenario. She used to always say she wanted to be a mother. ‘But I don’t necessarily feel that way anymore.’

I have growing doubts about whether I should have children

She’s combining her studies with a job she’s held for the past five years, but she doesn’t think she’ll be able to afford a home in which she can raise a family. ‘While my salary has gone up, my spending power has actually decreased. I can also see new parents around me struggling to keep their heads above water, financially speaking.’

Irene doesn’t want that. ‘I honestly wonder sometimes if it’s even feasible to want kids.’

What if my kid is queer? They’ll feel unwanted

Many other students consider the rising housing prices an obstacle to their desire to have children. ‘Most young people will never be able to buy a house’, one of the respondents says. Media studies student Jørgen Henriksen (24) isn’t optimistic, either. ‘The idea that I’ll ever be able to own my own home is so far-fetched.’

Compared to earlier generations, young people today have to invest considerably more money in order to purchase their own space. ‘I also expect the economy to tank even further’, Jørgen adds. ‘So if I do have a child, they’ll grow up in an even worse financial situation than I did.’

His current budget certainly doesn’t include children. ‘In Norway, where I come from, single life is already really expensive. I’d rather spend my money on myself and my future girlfriend or wife.’

Right-wing politics

Another factor for students is a lack of confidence in the political situation. ‘The current climate of right-wing politics doesn’t exactly encourage me to start a family’, says one of the respondents.

I feel like more and more friends are considering NOT having children

Marine biology student Yannick Hill (29) is worried about what will happen if politics continue to become more far-right. ‘Minorities will be affected even more. What if my kid is queer? They’ll feel unwanted and that will negatively affect them.’

He also doesn’t think politics will do much to change the situation. ‘I don’t see any improvement happening any time soon. It feels as though we’re on the brink of large-scale economic or societal collapse.’

Not optimistic

In fact, few students are optimistic about the future. One of the survey respondents said: ‘Just look at all the problems we’re currently facing: war, exploitation, hierarchies, and immense differences in gender, race, nationality, class, culture, etc.’

What kind of world would I be bringing a child into?

‘I don’t think enough is being done to improve the world for the coming generations’, says Sanne Otter (23), who’s doing the master writing, editing and mediating. ‘What kind of world would I be bringing a child into?’

But say she does have a kid: ‘I’d want them to have as few bad experiences as possible. But there are only so many problems you can tackle as an individual.’ Large-scale matters like climate change, for instance, require institutional change.

Climate change

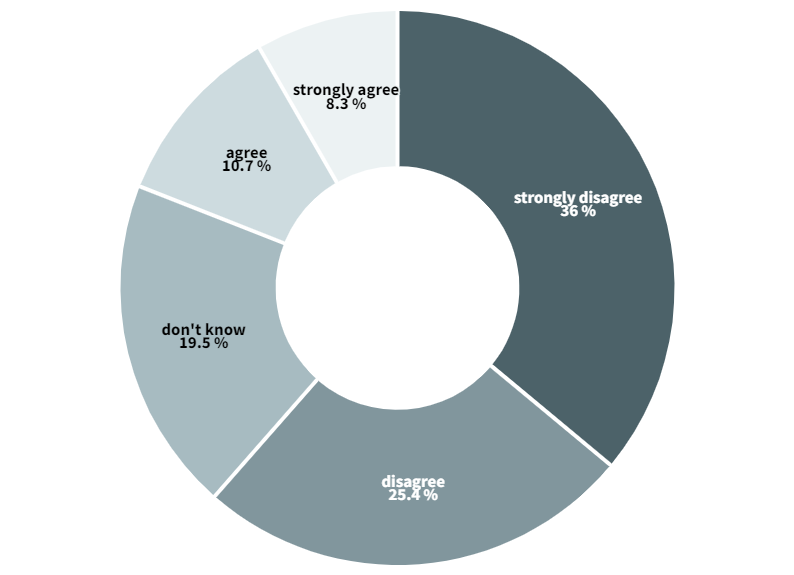

Climate change is in fact one of the issues that factor into students no longer thinking having children is the obvious choice. Nearly 37 percent of respondents said that environmental concerns and climate change was a reason to remain childless.

It is irresponsible to have children, given the problems in the world

This tendency hasn’t gone unnoticed at the Urology Clinic Groningen; a surprising number of young men have been coming here to get sterilised. They often cite climate change as the reason. ‘We hardly ever got that ten years ago’, says urologist Willemijn Windt.

How things have changed in 2024. ‘I think having a child is the most environmentally unfriendly thing a person can do with their life’, says student of spatial planning and design Timothy Laukens (20). ‘Nothing requires as much resources and energy as a human being.’

Scientists have calculated that in developed nations, having one child equals 58 tonnes in CO2 emissions a year. If a flight from Europe to the United States produces 1,6 tonnes of CO2, having a child equals thirty-six flights. A year.

Overpopulation

‘Besides, the world is overpopulated and people in the West over-consume’, says Timothy. Then there’s another issue: ‘When it comes to climate change, we need to get on a world-wide level of action to prevent it. But so far, that hasn’t seemed to work.’

A lot can happen in young people’s lives

He thinks that in the end, everyone is free to make their own choices. ‘But I’d personally hate condemning a child to live in the current world.’

He’s lost all faith in governments. ‘For the people in power, their interest lies solely in economic growth and profit’, he says. That means they will not be the ones to solve the climate crisis – in fact, they’re the catalyst.

Change their minds

Another reason climate change is such a unique concern for students is the hopelessness of the situation, says assistant professor of population studies Billie de Haas. ‘I can imagine that people think climate change is only going to get worse.’

But these large-scale problems aren’t solved by the individual choice of not having children, she says. ‘It’s really about corporations and governments changing their policies.’

Family sociologist Gert Stulp says the situation is more nuanced than students think it is. ‘A lot can happen in young people’s lives to change their minds’, he says.

What if you meet a partner who does want kids, for instance? What if all your friends start having babies, or your urge to have one yourself becomes stronger as you age? Things like these can make people reconsider. ‘It’s partly biology’, Stulp explains. ‘Nevertheless, a quarter of students saying they don’t want children is quite a lot.’